|

Cover

Story

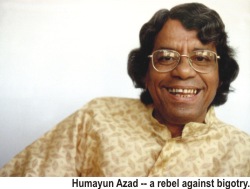

Humayun

Azad Humayun

Azad

A

Truncated

Life

MUSTAFA

ZAMAN

and

AHMEDE HUSSAIN

While

lamenting his death, one of Humayun Azad's illustrious classmates

wrote, "His death is a reminder of the tragedy of the

Greek god Icarus." On a poetic plateau, this may be one

way of expressing Humayun Azad's rise to fame and his sudden

demise. However, we do not live in myths or epics, let alone

be affected by their magic or overwhelming sense of fatality.

As humans we tread on the treacherous ground of reality, where

our own sets of interests and aspirations are constantly being

challenged by those of others'. Writer, poet, academic Dr

Humayun Azad had to deal with real enmity in all its sinister

implications. Although, Azad was a poet himself, for him,

there was no room for poetic gesture to characterise his own

plight that befell him since the machete attack on February

27, 2004.

Although

Azad came back apparently fully recovered and showing clear

signs of rejuvenation, the last three months of his life was

like living under the shadow of death. Anonymous callers kept

threatening him and his family. Even an abduction attempt

on his son was made on July 5. What was termed by his well-wishers

as "a triumphal return" was soon marred by despotic

efforts allegedly by Islamic extremist elements to thwart

his intellectual pursuits and mar his family's peace.

Even

before the attempt on his life, Azad was constantly being

intimidated by this quarter. He was dubbed a murtad

(apostate) by the religious zealots long before the attempt

on his life. Since the day his first novel, Chhappanno

Hajar Borgomile became a runaway success in 1994, the

fear of that same quarter magnified in the face of the power

of his sharp and witty tongue and his prolific pen. They marked

him out as an "enemy of Islam". The last 10 years

of his life can only be summed up as one man's struggle against

the escalating domination of the religious right. Even

before the attempt on his life, Azad was constantly being

intimidated by this quarter. He was dubbed a murtad

(apostate) by the religious zealots long before the attempt

on his life. Since the day his first novel, Chhappanno

Hajar Borgomile became a runaway success in 1994, the

fear of that same quarter magnified in the face of the power

of his sharp and witty tongue and his prolific pen. They marked

him out as an "enemy of Islam". The last 10 years

of his life can only be summed up as one man's struggle against

the escalating domination of the religious right.

Was Azad

a left-of-the-field thinker? Was he a politically correct

voice in a politically corrupt nation? In fact, these are

the characteristics Azad religiously avoided, or so it seemed

from the stream of writings and commentaries that he produced

during the last decade of his life. Being a freethinker, he

often acted like a rebel, perhaps to defy labeling, or to

vent his disenchantment over the deteriorating scenario of

his beloved motherland. He was, in fact, a maverick among

the academics of Dhaka University, where he used to teach

in the Department of Bangla.

As

a writer, Azad was critically engaged with his surroundings.

Publicly known for his passionate and opinionated temperament,

Azad had a mellow private side to his character that many

may not have known before his death. He was a family man with

a strong attachment to his children and wife. In his professional

life, during many an academic procedure, while making crucial

official decisions along with his colleagues, Azad used to

concede his position to respect the other person's opinion. As

a writer, Azad was critically engaged with his surroundings.

Publicly known for his passionate and opinionated temperament,

Azad had a mellow private side to his character that many

may not have known before his death. He was a family man with

a strong attachment to his children and wife. In his professional

life, during many an academic procedure, while making crucial

official decisions along with his colleagues, Azad used to

concede his position to respect the other person's opinion.

Humayun

Azad was born on April 28, 1947 in the village of Rarikhal

of Bikrampur district. The village was already famous for

being the birth place of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, a scientist

of international repute. In 1962, Azad completed his ISC (equivalent

to HSC) from the school that takes after the scientist's name

-- Sir JC Bose Institution. As he secured a position in the

merit list his future course led him to the highest seat of

learning, Dhaka University. He completed his BA in Bangla

in 1967 and MA in the same subject the next year.

Abu Kaiser,

one of his fellow students in the department of Bangla, Dhaka

University, remembers Azad as the student who used to don

"a Bonde Ali Miah-like hair-do" and "whose

reticence belied his intelligence and his goonpona (creativity)".

And he went on to add that Azad used to befriend only the

meritorious students of his class and had little time to waste

in idle chit chat.

"We

were politically active and were attached to different student

organisations. However, Azad stayed away from the hubbub of

real polity," wrote Kaisar in a recently published article.

But Azad first became famous for a political poem he wrote

during his student life. "Blood Bank" was the poem

that made a ripple in the campus. It even went beyond that

when people started to consider it a testimony to the political

climate of the '60s, which was severely subjugated to the

military rule. The poem was published in Kolkata in the weekly

"Desh" and the "Amrito". "We

were politically active and were attached to different student

organisations. However, Azad stayed away from the hubbub of

real polity," wrote Kaisar in a recently published article.

But Azad first became famous for a political poem he wrote

during his student life. "Blood Bank" was the poem

that made a ripple in the campus. It even went beyond that

when people started to consider it a testimony to the political

climate of the '60s, which was severely subjugated to the

military rule. The poem was published in Kolkata in the weekly

"Desh" and the "Amrito".

Mashukul

Haq, editor of the Observer Magazine and a classmate of Azad

remembers him as a brilliant student "who came from a

science background and switched to Bangla and turned out to

be the best in his class." "He was also impulsive

in nature, and it was evident at an early stage that he was

destined to become a rebellious voice," he adds. Haq

considers him a voice against those who use religion as a

political tool.

Latifa

Kohinoor, who later became the wife of Azad, and her numerous

friends were virtually in awe of Azad's intellectual capacity

to comment on every other subject. It was poetry and letter

that brought the couple together; till this day Latifa considers

Azad her favourite poet.

The

couple got married on October 12, 1975 and they " lived

in Scotland for one year". Right after Azad came back

from his study in Edinburgh, where he completed his PHD in

1996, they started their lives in a joint family. The

couple got married on October 12, 1975 and they " lived

in Scotland for one year". Right after Azad came back

from his study in Edinburgh, where he completed his PHD in

1996, they started their lives in a joint family.

"He

was a responsible father. When the children were born, it

was Azad who used to take care of them most of the time as

my job kept me away from home from nine in the morning till

five in the afternoon," Latifa remembers. For a man of

letter, he was too anchored in the peace and quiet of family

life. His two daughters and only son constituted the centre

of his life.

Azad started

his professional life as a teacher in Chittagong College.

After a brief stint at that college he joined Chittagong University.

Later he joined as a teaching staff of Jahangirnagar University,

where he taught Bangla from 1976 to 1977 before finally joining

Dhaka University in 1978 as an Associate Professor. It was

not until 1986 that he was made a Professor where he remained

so till his sad demise.

In

1973, while he was still a teacher at Chittagong University,

Azad got a scholarship at Edinburgh University. It was here

that he, with his grounding in Bangla literature, got the

opportunity to delve into linguistics. During his three year

study he produced his first thesis on language, which was

his PhD paper: "Pronominalisation in Bangla". In

1973, while he was still a teacher at Chittagong University,

Azad got a scholarship at Edinburgh University. It was here

that he, with his grounding in Bangla literature, got the

opportunity to delve into linguistics. During his three year

study he produced his first thesis on language, which was

his PhD paper: "Pronominalisation in Bangla".

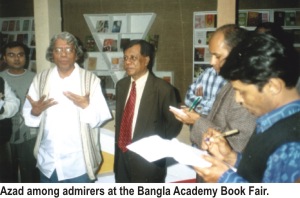

Although

he made his name as a poet while he was still a student, his

essays were revered by many from the beginning. The novelist

Azad first emerged in the pages of a literary supplement of

the Daily Ajker Kagoj with his Chhappanno Hajar

Borgomile. It was 1993, and the novel was well received

by the readers. They recognised in it a genre of its own kind.

In fact, through this first novel he started enjoying a wide

readership for the first time. The serially published novel

was later reintroduced in book form. It came out during the

Bangla Academy 'Book Fair' in 1994 and it was one of the much-sought-after

books of that year that saw its third edition during the month-long

fair. Azad's wife Latifa Kohinoor remembers the time as one

of the most crucial landmarks in their lives. Azad not only

became a popular writer, he soon positioned himself as a popular

spokesman in his community, and it was from this point on

that his ideas started to receive flak from a certain quarter

steeped in despotic religious beliefs.

"He

was a scholar set out to explore the world of linguistics.

There was no financial reward for what he was doing, so it

was I who kind of challenged him by asking, 'will you be able

to write novels?'" recalls Latifa Kohinoor. Azad's answer

was unmistakably bold. "He said, 'I could and my first

novel will be a hit'," remembers Kohinoor. This was a

display of his characteristic confidence .

Sajjad

Sharif, a poet and one of the Deputy Editors of the Daily

Prothom Alo, believes that Azad's most important contribution

was in linguistics. "He had a lot to contribute in Bangla

language in its grammar. After all these years we still do

not have our own grammar. Humayun Azad understood the mutating

nature of grammar and realised the importance of liberating

it from its present English and Sanskrit foundation,"

Sharif adds. "Azad came up with an original idea to write

Bangla grammar. He submitted his plan to the Bangla Academy.

It was written in an essay form and was published in a journal,"

continues Sharif, who thinks the Academy failed to understand

the depth and breadth of his proposal. Sajjad

Sharif, a poet and one of the Deputy Editors of the Daily

Prothom Alo, believes that Azad's most important contribution

was in linguistics. "He had a lot to contribute in Bangla

language in its grammar. After all these years we still do

not have our own grammar. Humayun Azad understood the mutating

nature of grammar and realised the importance of liberating

it from its present English and Sanskrit foundation,"

Sharif adds. "Azad came up with an original idea to write

Bangla grammar. He submitted his plan to the Bangla Academy.

It was written in an essay form and was published in a journal,"

continues Sharif, who thinks the Academy failed to understand

the depth and breadth of his proposal.

Sharif

believes that the most important works of Azad are the two

hefty volumes of his compiled works on Bangla language where

the best write-ups of the last one and half hundred years

are compiled. "He wrote elaborate and lengthy prefaces

that undoubtedly brought out the best in him," Sharif

contends. "While in Kolkata I heard people wondering

about Azad's ability to bring out two huge tomes and write

such wonderful essays to go with them at a young age,"

exclaims Latifa.

As

a writer who produced 70 books, Azad's acknowledgement mostly

came from his readers. He was one of the writers whose collections

of essays could become best sellers. “Nari

is one of his best books," believes Sajjad Sharif, who

also considers his Lal Neel Dipaboli and Koto

Nodi Shorobor, written for children, as two of his most

important works. For his contribution to literature he received

the Bangla Academy award in 1987. As

a writer who produced 70 books, Azad's acknowledgement mostly

came from his readers. He was one of the writers whose collections

of essays could become best sellers. “Nari

is one of his best books," believes Sajjad Sharif, who

also considers his Lal Neel Dipaboli and Koto

Nodi Shorobor, written for children, as two of his most

important works. For his contribution to literature he received

the Bangla Academy award in 1987.

Syed

Mehdi Momin, a journalist of The Independent, writes in an

article that Azad never wanted to associate himself with the

culture of sycophancy which he was surrounded by. He himself

was a man who never swerved from what he felt like saying.

Even "his literal handshake with death could not subdue

his spirit," Momin wrote.

A

few days before he left for Germany on another scholarship

from PEN (an international organisation of poets, essayists

and novelists), Azad, as usual, lambasted the religious right,

yet he ended his speech on a positive note. He said that the

"future of Bangladesh is not that bleak". With this

last note of optimism he left the country for Munich, Germany.

Azad was never a person who craved to retreat from his own

land; escape was the last thing on his mind. Although he was

known to many as being confrontational in nature, Azad was

a patriot with a deep sense of belonging to his own land.

"He used to become restless in Dhaka and needed to retreat

to his own village once every month. Rarikhal, his home village,

was a life saver to him," asserts Latifa. A

few days before he left for Germany on another scholarship

from PEN (an international organisation of poets, essayists

and novelists), Azad, as usual, lambasted the religious right,

yet he ended his speech on a positive note. He said that the

"future of Bangladesh is not that bleak". With this

last note of optimism he left the country for Munich, Germany.

Azad was never a person who craved to retreat from his own

land; escape was the last thing on his mind. Although he was

known to many as being confrontational in nature, Azad was

a patriot with a deep sense of belonging to his own land.

"He used to become restless in Dhaka and needed to retreat

to his own village once every month. Rarikhal, his home village,

was a life saver to him," asserts Latifa.

"He

went abroad for two years, and this was a man who could not

live in America for more than two months. We thought, in the

face of all the hostility, it would be wise to leave the country,"

exclaims Latifa. His near ones as well as his string of well-wishers

never thought that it would be his last farewell. In the end

what is left is the saga of a man who started out as a brilliant

essayist and later decided on a mode of expression, which

was a novel and that brought him popularity as well as the

wrath of a vested quarter. What more is to be found is his

imprint in all the outpourings of his creativity.

On

the evening of that fateful Friday, Humayun Azad, in jeans

and fatua, was sitting at the stall of Agami Prokashani at

the Amar Ekushey Book Fair. "Azad left the fair at around

8:45 in the evening telling me he would go home," says

Osman Gani, owner of the publishing house. When he reached

the pavement outside the Bangla Academy, a young man approached

him for an autograph; Dr Azad obliged and crossed the road

for a rickshaw. And then two unknown assailants, armed with

chopping knives, hacked the 56-year-old writer several times

on the jaw, lower part of the neck and hands. On

the evening of that fateful Friday, Humayun Azad, in jeans

and fatua, was sitting at the stall of Agami Prokashani at

the Amar Ekushey Book Fair. "Azad left the fair at around

8:45 in the evening telling me he would go home," says

Osman Gani, owner of the publishing house. When he reached

the pavement outside the Bangla Academy, a young man approached

him for an autograph; Dr Azad obliged and crossed the road

for a rickshaw. And then two unknown assailants, armed with

chopping knives, hacked the 56-year-old writer several times

on the jaw, lower part of the neck and hands.

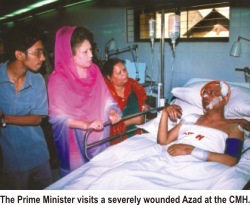

Conscious

but profusely bleeding, Dr Azad was taken to the nearby Dhaka

Medical College Hospital (DMCH). According to newspaper reports

, no doctor was available at the emergency unit of the DMCH;

Azad was later sent to the Combined Military Hospital(CMH).

Dr

Azad had been fearing for his life ever since excerpts of

his new novel, Pak Sar Zamin Shaad Baad (Pakistan's

national anthem; Blessed be the Sacred Land) was first published

in the Daily Ittefaq's Eid supplement in 2003. In

an email to Muktomona, an independent website, Azad wrote,

"The Ittefaq published a novel by me named Pak Sar

Zamin Shaad Baad in its Eid issue in December 3. It deals

with the condition of Bangladesh for the last two years. Now

the (religious) fundamentalists are bringing out regular processions

against me, demanding exemplary punishment. The attached two

files with this letter will help you understand." Dr

Azad sent two photographs along with the mail.

Dr

Azad's assailants, in fact, might have come right out of the

very book, which had put his life under increasing threat.

It depicts the story of a zealot who wants to establish a

"Taliban-styled distorted Pakistan" in Bangladesh.

"We aren't alone, our brothers all over the world are

doing their work. If they fly an aeroplane into a building

somewhere, if cars crash into a hospital or a hotel, or if

a bomb blast kills 300 people in some recreational centre,

then we know it's the work of our brothers; in other words

it is our work, it is Jihad," the protagonist of the

book, a member of Jama-e-Jihad-e-Islami Party, says in a monologue. Dr

Azad's assailants, in fact, might have come right out of the

very book, which had put his life under increasing threat.

It depicts the story of a zealot who wants to establish a

"Taliban-styled distorted Pakistan" in Bangladesh.

"We aren't alone, our brothers all over the world are

doing their work. If they fly an aeroplane into a building

somewhere, if cars crash into a hospital or a hotel, or if

a bomb blast kills 300 people in some recreational centre,

then we know it's the work of our brothers; in other words

it is our work, it is Jihad," the protagonist of the

book, a member of Jama-e-Jihad-e-Islami Party, says in a monologue.

The

name Jama-e-Jihad-e-Islami is believed to be an allegory to

the Jammat-e-Islami Bangladesh (JI), one of the major partners

in the ruling four-party coalition government. In fact, Karim

Ali Islampuri, another character of the book says, "We

must seize power. Right now, we are with the power and the

main party. At some point, power will come to us; we will

become the main party. We are entering everywhere-- Islam

will be established; (another) Pakistan will be created. There

won't be any infidels, Malauns (Hindus); there won't be any

Hindu or Jew in guise of Muslims."

JI,

in its response, took the content of the Pak Saar Zamin

Shaad Baad quite seriously. On January 25, Maulana Delwar

Hossain Sayeedi, a JI MP demanded the introduction of the

Blasphemy Act to block the publication of "such books".

Besides Sayeedi, many bigots declared the famous writer a

murtad (apostate). Momtazi, emir of Hifazate Khatm-e-Nabuat

Movement and Imam of Rahim Metal Mosque demanded the professor's

arrest and trial on December 12, only months before the attack.

The BNP-led four-party alliance did nothing to nab those who

were issuing death warrants to one of the most eminent linguists

of the country. JI,

in its response, took the content of the Pak Saar Zamin

Shaad Baad quite seriously. On January 25, Maulana Delwar

Hossain Sayeedi, a JI MP demanded the introduction of the

Blasphemy Act to block the publication of "such books".

Besides Sayeedi, many bigots declared the famous writer a

murtad (apostate). Momtazi, emir of Hifazate Khatm-e-Nabuat

Movement and Imam of Rahim Metal Mosque demanded the professor's

arrest and trial on December 12, only months before the attack.

The BNP-led four-party alliance did nothing to nab those who

were issuing death warrants to one of the most eminent linguists

of the country.

The

government however, finally took the matter seriously. Dr

Azad was sent to Bumrungrad Hospital in Thailand; and the

maverick writer was, slowly but steadily, recovering. "You

don't know how happy I was then," says Latifa.

That did

not last long; the whole situation changed for the worse as

soon as the Azad was back home. "The zealots were back

too and they started threatening us on the phone," Latifa

says. In the last six months the family has been through extreme

insecurity. "Then they threatened to bomb our house on

Fuller road," Latifa says.

The

systematic persecution, actually, reached its zenith at the

time when Dr Azad decided to give his research project on

German poet Heinrich Heine a second thought. "Azad had

wanted to do research on Heine long before the attack; He

had even prepared all his notes by the end of December,"

says Latifa Kohinoor. The writer, however, did not get any

response from the PEN; and when it came about two months after

the attack, Latifa felt uneasy. The

systematic persecution, actually, reached its zenith at the

time when Dr Azad decided to give his research project on

German poet Heinrich Heine a second thought. "Azad had

wanted to do research on Heine long before the attack; He

had even prepared all his notes by the end of December,"

says Latifa Kohinoor. The writer, however, did not get any

response from the PEN; and when it came about two months after

the attack, Latifa felt uneasy.

Dr Azad, too, had second thoughts before he boarded the plane

for Munich. "Azad talked with almost everyone he knew

about the scholarship," Latifa recalls. She was against

the idea of her husband leaving the country as she thought

it would separate the family and he would not eat properly

which would affect his health. "He was a very bad cook,"

Latifa smiles shyly. But Azad's wife withdrew whatever reservations

she had when their only son Anonno was kidnapped days before

the writer's planned departure.

"Three

bearded men frisked Anonno away while he was returning from

school. They took him to an abandoned house near the SM Hall

and asked him about Azad's fellowship," Latifa says.

Two of them were tightly holding Anonno's hands while the

other was asking him when his father would leave the country,

she says. As one of the kidnappers whispered something in

the other's ear; Anonno broke free from their grasp and ran

home.

Dr

Azad, however, reacted to his son's kidnapping with uncharacteristic

calmness; "as if he knew this would happen," Latifa

shudders while describing the event. But the writer, who was

drafting his new novel titled Mrityur Ek Second Durey

(A Second Away From Death), could not escape death in Munich.

Dr Humayun Azad was found dead in his Munich apartment by

a fellow PEN member. Dr

Azad, however, reacted to his son's kidnapping with uncharacteristic

calmness; "as if he knew this would happen," Latifa

shudders while describing the event. But the writer, who was

drafting his new novel titled Mrityur Ek Second Durey

(A Second Away From Death), could not escape death in Munich.

Dr Humayun Azad was found dead in his Munich apartment by

a fellow PEN member.

Rumours

ran amok when the news of Dr Azad's death broke out. His family

still believes the fundamentalists could not kill him here,

so they followed through with their plan in the German city.

"How is it possible that the person we saw alive and

well here in Dhaka a few days ago, all of a sudden fell sick

and died of a heart attack?" Latifa asks. "He called

home only two days before they poisoned him to death. In this

era of modern science you will never be able to find out the

truth," she says.

Controversy

however did not leave Dr Azad, arguably the last outspoken

Bangali writer, even after his death. "The fundamentalists

are still threatening us on the phone. Someone called yesterday

and told me 'Humayun Azad could not escape from our grasp;

we hunted him down in Germany. Now it is your turn',"

says Latifa. "I do not know what we have done to them

to deserve this," she continues; "What problem can

they have with a dead writer's family?" Latifa Kohinoor

asks.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|