|

Cover

Story

What

Ails DMCH?

AASHA

MEHREEN AMIN and AHMEDE HUSSAIN

Photographs:

Zahedul I Khan

The

Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH) is the largest public

hospital in the country. For those who cannot afford the high

fees of private hospitals or clinics, the DMCH is the only

hope for getting cured. In the event of an emergency, it is

often the only option. Even patients from far-off places in

the country come all the way to DMCH in the absence of beds

or proper medical treatment in their own districts. But in

spite of its crucial role in our ailing health care system,

the DMCH is a house of endless horror stories. Rampant corruption,

years of unhindered politicisation of the entire institution

and an unrealistically poor budget have turned DMCH into a

hellhole for the sick. The

Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH) is the largest public

hospital in the country. For those who cannot afford the high

fees of private hospitals or clinics, the DMCH is the only

hope for getting cured. In the event of an emergency, it is

often the only option. Even patients from far-off places in

the country come all the way to DMCH in the absence of beds

or proper medical treatment in their own districts. But in

spite of its crucial role in our ailing health care system,

the DMCH is a house of endless horror stories. Rampant corruption,

years of unhindered politicisation of the entire institution

and an unrealistically poor budget have turned DMCH into a

hellhole for the sick.

The first

thing that hits one in the face upon entering Dhaka Medical

College Hospital (DMCH), which looks more like a medieval

mansion in a gothic horror movie, is the noxious, suffocating

smell. It comes from a mixture of grimy floors, stale sweat

and general claustrophobia of this gigantic maze where inhaling

too deeply might make you faint. Pungent enough to make a

healthy person fall sick, it is the smell of gross negligence.

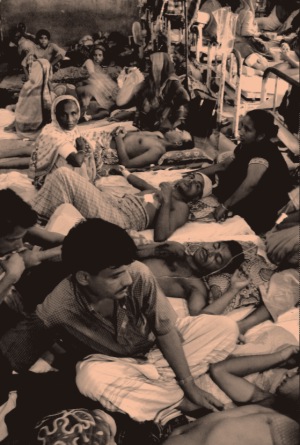

Signs

of utter disrespect for human life are everywhere. On a busy

day when the wards are all filled up, the corridors outside

are strewn with sick patients, men, women and babies, some

waiting to be healed, others waiting to die.

Nine-year-old

Tanvir lies sleeping on the floor outside Ward 35 with a bandage

on his head and a saline apparatus next to him. His father

informs us that Tanvir fell from the terrace of their flat

in Hosni Dalan. "We brought him here and after initial

treatment we had to take him home as they told us that there

was no bed," he says as Tanvir's mother keeps looking

at her son. But Tanvir's condition deteriorated that night

and his parents had to rush him back to the hospital. "We

have to buy all the medicine ourselves from outside. I got

mad because why should we have to buy all this when this is

a government hospital and is supposed to provide free medicine?"

Most of

the drugs the doctors at the DMCH prescribe come from government-run

Essential Drugs Company Limited (EDCL). Drugs that the EDCL

does not produce are bought in an annual open tender by the

hospital. Usually a purchase committee is formed to assess

the need for drugs the hospital has in each fiscal year. "But

nepotism and corruption rule most of the purchasing,"

says Zaman (not his real name), a Class Three employee. He

alleges that in most cases the doctors refuse to prescribe

the sub-standard drugs that the hospital has purchased through

its annual tender, thus forcing the patients to buy drugs

from the dispensaries outside DMCH. "Some Class Four

employees steal essential drugs and sell them to different

drugstores across the country," he adds.

Failing

to get a bed many patients stay under the banister with their

attendants

According

to a senior official of the hospital administration, while

the DMCH has a supply of basic drugs and medical supplies

like syringes, gauze, saline, etc., some drugs such as expensive

antibiotics have to be bought by the patients because they

are not available at the hospital medicine store. The official

however, evaded the issue of drugs being stolen or sold off

outside the hospital.

Standing

in the corridor is a young woman trying to soothe her baby

-- just over a month old. Parveen Islam had to come all the

way from Chandpur when her newborn baby's stomach became abnormally

inflated. After being refused from Shishu Hospital and Mitford

Hospital because there were no beds vacant, she ended up at

DMCH, where, miraculously, she did get a bed. It took 10 excruciating

days of tests before the doctors diagnosed the problem: an

intestinal complication. "We had to do all the tests

outside because the tests done at DMCH are not accepted by

the doctors," says Parveen's brother.

Encouraged

by Parveen, other people come forward and give their list

of grievances. "The nurses are extremely rude, especially

the younger ones," says Shaheen, whose niece is a patient. Encouraged

by Parveen, other people come forward and give their list

of grievances. "The nurses are extremely rude, especially

the younger ones," says Shaheen, whose niece is a patient.

"The

food the cooks give us is substandard and they never give

enough rice. We have to buy rice from the cooks for Tk. 5,"

she continues. Amanullah (not his real name), a ward boy,

echoes the allegation and has his own Pandora's box of the

evils committed in the hospital. According to him, the cooks

sell raw eggs and boiled eggs outside the hospital and cooked

food to the patients although food is supposed to be free

of cost. "The cooks themselves eat the best part of the

food and also give it to the hospital employees' union leaders

to keep them happy."

Food,

moreover, is not the only item sold to make a quick buck.

According to Amanullah, some doctors and nurses form an understanding

whereby the doctors over-prescribe drugs of a patient and

then the extra drugs are sold off. "Medicine is often

stolen by OT (Operation Theatre) ward boys, OT sisters and

even doctors," says Amanullah.

But

the more obvious anomaly is the unbelievable filth in the

wards where many patients are critically injured. Several

weeks ago while visiting a patient -- a young garment worker

who had been raped and her spinal cord almost completely severed

-- we saw scores of little cockroaches all over the walls.

Some of them were running up the patient's body. The floor

where more patients were lying on was sticky with grime. Two

cats freely wandered around the wards, looking for scraps. But

the more obvious anomaly is the unbelievable filth in the

wards where many patients are critically injured. Several

weeks ago while visiting a patient -- a young garment worker

who had been raped and her spinal cord almost completely severed

-- we saw scores of little cockroaches all over the walls.

Some of them were running up the patient's body. The floor

where more patients were lying on was sticky with grime. Two

cats freely wandered around the wards, looking for scraps.

The stink

from the bathrooms waft into the corridors; the floors are

wet and muddy with discarded food strewn all over. "In

such unhygienic conditions how can sick patients survive,

especially those who run the risk of contracting infections?"

asks Shaheen.

"The

ayahs are supposed to clean everything," says

Sharmin, a patient's sister, "but if we don't give them

money they refuse to do it."

Class

Four employees, who include the Sweepers, Zamadars, and Sardars

are not transferable. This, Zaman believes, has given them

perpetual immunity from any administrative action for negligence

of duty. "They cannot be transferred as long as the case

is 100 per cent proven against them," says Zaman.

Class

Four employees have their own union, which is affiliated with

both the ruling and the opposition parties. And though the

union leaders draw their salary year in and year out, they

seldom lift a finger as far as work is concerned. "There

are seven ward-masters in the whole hospital, and around three

Sardars work under them," says Zaman. On an average,

he continues, a ward master has to supervise 150 people. "But,

most of them," Zaman alleges, "do not even turn

up at work." And like their supervisors, most Class Four

employees who work under them regularly shirk their responsibilities.

The

DMCH administration turns a blind eye to this, as they are

large in number and most Class Four union leaders are involved

in party politics. "You can't do anything if a ward boy

or an ayah misbehaves with you. Once a Director General

reprimanded a sweeper for not cleaning the ward properly;

that DG was later transferred because his political power

outmatched that of the sweeper's," Zaman recalls. The

DMCH administration turns a blind eye to this, as they are

large in number and most Class Four union leaders are involved

in party politics. "You can't do anything if a ward boy

or an ayah misbehaves with you. Once a Director General

reprimanded a sweeper for not cleaning the ward properly;

that DG was later transferred because his political power

outmatched that of the sweeper's," Zaman recalls.

In fact

ward boys can hardly be seen at the Emergency Unit of the

hospital where they are supposed to attend to the patients.

In the absence of the ward boys, a gang of brokers, in connivance

with the Class Four employees, runs a thriving business of

luring patients to nearby private clinics. "After grabbing

the patients, the brokers huddle them into a waiting ambulance

to take them to the nearby clinic. Each broker usually makes

from Tk 4,000 to 6,000 a month. And the commission is about

Tk 200 for a delivery patient and Tk 500 to 1,000 for general

surgery like hernia, cleft-lip and minor burn," writes

Shamim Ashraf in a Daily Star report.

The list

of allegations is endless. Getting a trolley for carrying

a patient costs Tk 100; relatives have to pay Tk 1,000 at

the morgue to get the dead out of the hospital. Duties of

DMCH's Blood Bank are sold every night to outsiders who buy

blood from drug addicts. All the revenues earned are distributed

equally among different unions.

"Everyone

in the DMCH wants to work in the blood bank," says Zaman.

Other most sought-after departments, according to Zaman, are

Ticket selling, Pathology and Morgue.

During

one of our visits to the Emergency unit we witnessed several

individuals (including one of us) being charged Tk10 for an

admission ticket when the official rate printed in bold on

the wall was

Tk 5.50.

According

to an official who preferred anonymity, unless complaints

are in written form, there is little the administration can

do.

"We

have received written complaints from letters and we have

taken action against the employee concerned in the form of

a suspension or cancellation of his yearly increment or retaining

the salary. We have to get the name of the offender to do

anything," says the official.

There

are worse horrors ahead. On Wednesday September 22 when we

enter DMCH, we are pleasantly surprised by the apparent clean

look in the ground floor corridors. The floors look reasonably

clean, the walls have been freshly whitewashed and miracle

of miracles, there are only faint traces of the formidable

smell that otherwise characterises DMCH. But it only takes

a flight of stairs up to Ward 35 to realise that nothing has

changed. Outside the corridor the body of a hit and run accident

is lying with a sheet drawn over the head. A man lifts the

sheet to see the mutilated face. He admits that he is not

a relative, or even a patient in the hospital. Just someone

randomly loitering around with morbid curiosity. Fatema Begum,

the relative of a patient says, the dead girl was a garment

worker who had been hit by a bus. "She was left here

all night without any saline and died at seven in the morning,"

she adds. There

are worse horrors ahead. On Wednesday September 22 when we

enter DMCH, we are pleasantly surprised by the apparent clean

look in the ground floor corridors. The floors look reasonably

clean, the walls have been freshly whitewashed and miracle

of miracles, there are only faint traces of the formidable

smell that otherwise characterises DMCH. But it only takes

a flight of stairs up to Ward 35 to realise that nothing has

changed. Outside the corridor the body of a hit and run accident

is lying with a sheet drawn over the head. A man lifts the

sheet to see the mutilated face. He admits that he is not

a relative, or even a patient in the hospital. Just someone

randomly loitering around with morbid curiosity. Fatema Begum,

the relative of a patient says, the dead girl was a garment

worker who had been hit by a bus. "She was left here

all night without any saline and died at seven in the morning,"

she adds.

At this

time it is already 2pm in the afternoon, i.e., over seven

hours. Right in front of the body, three other patients lie

helplessly in the corridors. One of them, a young woman called

Moina, is lying on a dirty piece of foam. It is hard to tell

whether she is sleeping or unconscious. Her attendant, a stranger

who happened to be in the same place as her when the accident

took place, says that Moina was hit by a double-decker bus.

During moments of lucidity she had given him her name and

the area where she lived. The man had paid for all the medicine

she needed but her relatives still had not been contacted.

Opposite

Ward 35 is Ward 35A, which is cramped, dark and damp. Patients

and their attendants are jam-packed together, making the air

difficult to breathe. Again, the floor of the ward is covered

by scores of patients who are still waiting for beds. The

overnight facelift downstairs is attributed to the Saudi Arabian

Health Minister's recent visit to the hospital. Opposite

Ward 35 is Ward 35A, which is cramped, dark and damp. Patients

and their attendants are jam-packed together, making the air

difficult to breathe. Again, the floor of the ward is covered

by scores of patients who are still waiting for beds. The

overnight facelift downstairs is attributed to the Saudi Arabian

Health Minister's recent visit to the hospital.

Zaman

blames the utter indifference that is so palpable all over

the hospital, on the politicisation of the DMCH administration.

"If you do not support the ruling party you will not

be able to work in DMCH," he says. "Whenever a new

government comes to power, the first thing the health ministry

does is issue transfer orders," Zaman continues. "Opposition

party followers will be marked out, and they will be transferred

to far away places outside the capital," he explains.

In

fact, immediately after coming back to power in 1996, the

Awami League (AL) transferred many doctors to different mufassil

towns for their involvement with the then opposition Bangladesh

Nationalist Party (BNP). That deplorable practice was repeated

when the BNP came to power in 2001.

To make

matters worse, every doctor in the hospital is actively involved

in national politics. "All the appointments made here

are political," Zaman says. "There are some posts

that an opposition party-member can never hold," he continues.

According to Zaman all the Resident Physicians, General Physicians,

ENT Surgeons and Eye Surgeons are active members of the ruling

party and they were appointed by the health ministry. In most

cases, a doctor's skill, experience and training take second

place over political affiliation.

o why

is the most important hospital of the city in such a sorry

state?

Low

salaries and lack of facilities contribute significantly to

the resentment among many DMCH doctors and nurses on government

payroll. Recently, around 73 nurses of DMCH (2,000 countrywide)

have not been getting any salary for the last four months

due to a bureaucratic glitch. But even in normal circumstances,

nurses feel they do not get paid enough for their services.

A nurse's basic salary is Tk. 2,225, and with rent and other

allowances included, it comes to about Tk. 4,900. Low

salaries and lack of facilities contribute significantly to

the resentment among many DMCH doctors and nurses on government

payroll. Recently, around 73 nurses of DMCH (2,000 countrywide)

have not been getting any salary for the last four months

due to a bureaucratic glitch. But even in normal circumstances,

nurses feel they do not get paid enough for their services.

A nurse's basic salary is Tk. 2,225, and with rent and other

allowances included, it comes to about Tk. 4,900.

"We

have no quarters and have to commute from far-off areas every

day," says Rahina Akhter, a senior staff nurse who has

been working at DMCH for the last 21 years. "Some nurses

come from as far as Gazipur and security is a big problem,"

adds Rahina, who is the Chairperson of Bangladesh Diploma

Nurses Association. Morjina Akhter, General Secretary of the

Association and also a senior staff nurse, adds that nurses

do not get other basic facilities like attached bathrooms

in the duty offices or a canteen to eat their meals or even

dressing rooms to change in. Supervisors are also very few.

There are only 31 supervisors for the 6,500 nurses at the

hospital.

Doctors

too, are ill-paid, especially considering their heavy workload.

A government-appointed Indoor Medical Officer (IMO) gets around

Tk. 6,800 at the entry level. Apart from regular duty from

8pm to 2:30am or 2:30am to 12pm, IMOs also have to do regular

night duty. Many IMOs therefore have private practices outside

DMCH.

"We

are not supposed to work anywhere else but how can we support

our families with such low pay?" says an IMO who now

gets around Tk. 8,000 per month.

According

to the hospital's accounts section, DMCH's budget for 2004-2005

is 27 crore 18 lakh 79 thousand taka. This includes 2 crore

5 lakh taka for salaried first class employees, another 5

crore 92 lakhs for 'non-gazetted' employees, about 8 crore

taka in allowances and 10 crore 74 lakh 95 thousand in medical

supplies (including Medical Surgical Requirement, MSR) and

80,000 taka for vehicle repairs. An extra 23 lakh taka was

allocated to buy a car for a high official and 20 lakh taka

for office furniture. According

to the hospital's accounts section, DMCH's budget for 2004-2005

is 27 crore 18 lakh 79 thousand taka. This includes 2 crore

5 lakh taka for salaried first class employees, another 5

crore 92 lakhs for 'non-gazetted' employees, about 8 crore

taka in allowances and 10 crore 74 lakh 95 thousand in medical

supplies (including Medical Surgical Requirement, MSR) and

80,000 taka for vehicle repairs. An extra 23 lakh taka was

allocated to buy a car for a high official and 20 lakh taka

for office furniture.

But this

is only about 30 percent of the hospital's required budget.

According to the Accounts Officer, a proposal had been given

for a budget of about 78 crore taka but was brushed aside.

Apart

from lack of funds, officials at the hospital complain about

a severe shortage of manpower. The hospital has expanded from

800 beds to 1700 beds but the number of fourth class staff

has remained at 900. Now out of this number there are 367

vacancies.

The

most pressing need at the moment is to have more beds. The

present 1700 beds are not enough, a dearth that leads to the

overcrowding on the floors of the wards with patients overflowing

into the corridors. "We try not to turn away any patients,"

says a high official of the hospital. The

most pressing need at the moment is to have more beds. The

present 1700 beds are not enough, a dearth that leads to the

overcrowding on the floors of the wards with patients overflowing

into the corridors. "We try not to turn away any patients,"

says a high official of the hospital.

"We

proposed an expansion of 600 beds two years ago. The government

has not taken the final decision yet," he says. "Medical

technology, in addition, has to be updated and for that you

need more funds."

On

a regular busy day, the hospital is in a chaotic state with

patients taking up whatever space they can find, even under

the staircase. Every day at least 1,000 patients come to the

hospital's Outdoor Section. In crisis situations such as after

August 21st's bomb blast in Purana Paltan, staff at DMCH were

working round the clock and could barely cope with the rush

of severely injured people. Patients being left for days without

being operated on and acute shortage of blood were reported. On

a regular busy day, the hospital is in a chaotic state with

patients taking up whatever space they can find, even under

the staircase. Every day at least 1,000 patients come to the

hospital's Outdoor Section. In crisis situations such as after

August 21st's bomb blast in Purana Paltan, staff at DMCH were

working round the clock and could barely cope with the rush

of severely injured people. Patients being left for days without

being operated on and acute shortage of blood were reported.

Still,

in the case of an accident or any other emergency, DMCH is

the only place where patients are not normally turned away

as is the case in other hospitals and clinics. Its importance

for ordinary people cannot be emphasised enough. But unless

the government recognises the crying need of a major overhaul

of the hospital, whatever limited healthcare it now provides

the poor, will increasingly substandard.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|