|

Personality

Storytelling

as a Learning Tool

Novera

Deepita

Once

in a session with children at the Commonwealth Institute in

London, a Gujrati girl asked Fahmida Monju Majid, 'What is

your religion?' The question was inspired by Monju's story

that used props representing different religions. Monju smiled,

'Well, I was born a Muslim.' Being curious the girl drew nearer

and whispered in Monju's ears, 'What are you now?' 'I am a

human being,' was the reply. The girl hugged Monju with a

smile and said, 'I am, too. This is the best religion.' Once

in a session with children at the Commonwealth Institute in

London, a Gujrati girl asked Fahmida Monju Majid, 'What is

your religion?' The question was inspired by Monju's story

that used props representing different religions. Monju smiled,

'Well, I was born a Muslim.' Being curious the girl drew nearer

and whispered in Monju's ears, 'What are you now?' 'I am a

human being,' was the reply. The girl hugged Monju with a

smile and said, 'I am, too. This is the best religion.'

This is

how Fahmida Monju Majid, the only professional storyteller

of the country, describes how broad a child's psychological

horizon can be. Involved with activities on the psychological

development of children since 1965, Monju works to help children

project their latent talent and abilities. She also teaches

them moral values and necessary social skills. Through storytelling

she tries to ensure these basic lessons of life.

According

to Monju, 'The importance of storytelling has been recognised

by recent scientific research. Stories, told in an attractive

manner, could be one of the best communicators for children.'

And Monju has turned storytelling into an art as she uses

instrumental and vocal sound effects, paintings, dramas, gigs,

puppets and other props that appeal to children.

Monju

prefers to tell stories at a pace easy for children to understand

and enjoy. Her style also differs from the ordinary rendition

of story telling. She describes an occasion: A puppet named

Khukumoni introduces Monju on the stage. She takes several

props with her. One of her props is a mask of a ghost, which

she has made herself in such a simple manner so that a child

can have the feeling that s/he can also make it. Sometimes

Monju imitates a monster that shouts at the prince, 'Fi-fy-fo-fum!

I smell the blood of a British man!' Sometimes she is the

bee with a hard-to-hear voice. She sometimes becomes the fairy

complete with wings. Through voice modulation she makes different

sound effects to match the theme of the story.

Monju

has conducted hundreds of storytelling sessions abroad and

uses sarees as props with which she portrays different things--a

sea with a blue saree, grass with a green one and the sun

with a golden one. With her teep on the forehead, fresh flowers

in her hair, draping Dhakai saree and glass bangles in her

hands she always presents herself as a traditional Bangalee.

She

tells the stories from Aesop's Fables, traditional folk or

fairy tales in the improvised version and even she makes up

stories on her own to teach the children some basic things.

For instance, she tells a story about circles and squares

to teach elementary geometry. Written by Monju, the story

is about a group of squares that used to make fun of the circles

saying, 'You are not that smart and beautiful because you

don't have edges like us.' So, the circles try to find ways

to change the notion of the squares. She

tells the stories from Aesop's Fables, traditional folk or

fairy tales in the improvised version and even she makes up

stories on her own to teach the children some basic things.

For instance, she tells a story about circles and squares

to teach elementary geometry. Written by Monju, the story

is about a group of squares that used to make fun of the circles

saying, 'You are not that smart and beautiful because you

don't have edges like us.' So, the circles try to find ways

to change the notion of the squares.

Monju

believes that children with special needs like the autistic

children and children in uncommon circumstances need physical

support or 'touch therapy'-- interactive sessions of story

telling. In a television programme in London, she was once

told not to hug and kiss the participating children. Monju

contradicted asking the producer, 'Don't you hug and kiss

your kids when you go home?' She explained to him how important

it is for the children as they find support and shelter through

affectionate touch.

Monju

feels that children can be made responsible through entertainment.

For example, if she wants the children to sweep the floor,

she asks them, 'What do we need to clean the dirt?' Maybe,

the children answered, 'A hand and a broom'; she then asks,

'What else do we need?' The children might look at each other

and wonder what would it be. With a giggle she shouts in joy,

'We need the wish to do this," which is the most important

thing because without it we cannot complete the task.' Then

with the enthusiastic participation of the children the work

is done!

About

the therapeutic use of storytelling Monju says, 'This is a

very effective technique to deal with children with social

and physical difficulties.' Therapeutic stories give messages

that deal directly with the unconscious mind of the listeners

with directives about love, power and healing. She asserts

that physically and mentally challenged children can be treated

through such therapy. Game therapy, for example, for average

children and touch therapy for the visually challenged can

have positive effects. She says, 'By adapting characters like

Ivan of the Russian fairytales who was very brave and Little

Red Riding Hood who suffered for not listening to her parents,

children can learn, realise and feel what is right and how

to do it.'

Monju

emphasises on this special technique: 'When all the child's

wishful thinking gets embodied in a good fairy, all his or

her destructive wishes in an evil witch, all his fears in

a voracious wolf, all the demands of the conscience in an

encounter on an adventure, all his jealous anger in some animal

that pecks out the eyes of his arch rival--then the child

can finally begin sorting out his contradictory tendencies.

Once this starts, the child will be least and least engulfed

by unmanageable chaos.' Monju

emphasises on this special technique: 'When all the child's

wishful thinking gets embodied in a good fairy, all his or

her destructive wishes in an evil witch, all his fears in

a voracious wolf, all the demands of the conscience in an

encounter on an adventure, all his jealous anger in some animal

that pecks out the eyes of his arch rival--then the child

can finally begin sorting out his contradictory tendencies.

Once this starts, the child will be least and least engulfed

by unmanageable chaos.'

For hearing

impaired children, the therapeutic use of pictures can make

them understand how the instruments play music and what is

sweet music. Monju says, 'When I tell stories to the children

who cannot walk, I do not say that the prince of the story

was running and chasing the monster to kill him. I'd say the

prince was flying instead.'

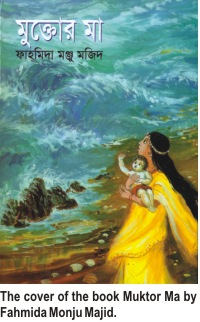

Monju,

who has specialisation in child psychology, has written several

books of fiction, fairy tales and poems. She also has been

conducting integration programmes since 1965. She explains

what is an integration programme: 'We put different things

together to make the children understand things they should

learn. There are no prejudices in such programmes.' Such integration

programmes include interactive sessions with children with

lots of paintings, puppets and other representative props. Monju,

who has specialisation in child psychology, has written several

books of fiction, fairy tales and poems. She also has been

conducting integration programmes since 1965. She explains

what is an integration programme: 'We put different things

together to make the children understand things they should

learn. There are no prejudices in such programmes.' Such integration

programmes include interactive sessions with children with

lots of paintings, puppets and other representative props.

Monju

is a registered storyteller of the Commonwealth Institute,

a regular host of programmes on the BBC radio and various

other television programmes on children. The granddaughter

of poet Gulam Mustafa and the niece of celebrated puppeteer

Mustafa Monowar, Monju considers her birth in such a family

as a blessing.

Emphasising

on the three P's of child rights, Protection, Provision and

Participation, Monju feels it is important for a child to

learn with interest. She boldly says, 'Education with entertainment

is more efficient than the old fashioned didactic system.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|