|

Dialogue

Dhaka--Stifled

by Lack of Planning

Fayza

Haq

Dhaka

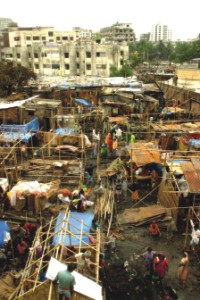

is a ramshackle, overpopulated city with indiscriminate construction

going on perpetually making city life more and more unbearable.

Over the last few decades this scenario has only gone from

bad to worse. So, who is responsible and what can we do about

it? Fayza Haq talked to a group of professionals who are concerned

about the plight of Dhaka city. They are architects Bashirul

Haq, Kashef Chowdhury and Albab Ahmed, artist Rafiqun Nabi

and journalist Ataus Samad. Here are excerpts of their opinions.

Bashirul

Haq: As we are a poor country, our transformation

from agriculture to industry was very slow. With the result,

some modes of transportation like the rickshaw lingered and

continue to linger. The rickshaw-pullers and their families

in Dhaka city alone would constitute close to a million people.

In the last 15-20 years with the growth of the garments industry,

people started living in temporary houses that barely gives

shelter. We have a serious problem with the growth of slums

in and around Dhaka. The problem primarily is housing of the

low-income group garment workers, rickshaw-pullers and low-paid

government employees also.

We need

express highways, mass transit systems. We have introduced

lots of busses. If you move around cities, you will find most

of the time the buses are clogging the streets. Buses are

short distance transport. If you take a bus from Gulshan to

Uttara, it will take an hour or an hour and a half, which

is a waste of time. That distance should not take more than

10-12 minutes. If we had express ways, mass-transit facilities,

high-speed trains etc, it would have been possible.

Town-planning

at the moment is very inadequate. The way to solve this problem

is to take housing for workers away form the city where it

will be affordable and people can come to work in high-speed

transport.

What can

we do to solve the housing problem for the poor? It can be

easily solved if planners, architects, economists, accountants

sit together and think of making something affordable for

the people. Or the government can create a loan system where

amortisation could be for 40 years where the repayment would

be lower.

Kashef

Chowdhury: Dhaka used to be a sort of a garden city.

The names suggest that-Shahbag, Kalabagan, Segun Bagicha.

Now it is very difficult to assign those adjectives to the

city because in the last 20/30 years the development that

has taken place has not been controlled.

The

way Dhaka is developing, it is like making a building without

a clear plan. Dhaka is becoming a linear city as it is growing

more on the north and south, particularly on the north. The

way Dhaka is developing, it is like making a building without

a clear plan. Dhaka is becoming a linear city as it is growing

more on the north and south, particularly on the north.

Dhaka

is like an island. All around us we have rivers. So the growth

of the city towards the Buriganga sort of ends as there are

no bridges, not enough connections. On the other side too

it's not growing. So the push is towards the north.

When a

city grows you have to be prepared for it to grow in an unexpected

way due to factors like financial prosperity, trade etc. and

then your town planning needs to incorporate such growth.

It needs to have projections to 30, 40, 50 years. Then may

be you need to revise these projections after 10 years.

There

are many garment industries within city limits. This is one

of the biggest foreign exchange earning industries so it is

very important. These industries are responsible for the slums,

as Bashirul Haq has said.

They live

in slums because they cannot afford the transport fare under

the current public transport system.

So if

we can have export processing zones (EPZ) dedicated to the

garment industry and the workers are given secure accommodation,

they will live there. Many young women working in the garments

industries lead an insecure life.

Albab

Ahmed: The original planning on paper for Dhaka city

was done in 1959 by the British. Then the population was about

2/3 lakhs. At the moment we have some 250 square kilometres

of area and a population of over 10 million. In 1995 there

was the Dhaka Metropolitan Development Plan (DMDP). It was

for the period between 1995 to 2015. But the plan is in one

place while the development is going on in another direction.

There were different zones-residential, commercial etc. in

the plan but unfortunately those were never implemented. You

see Dhanmondi was earmarked as a residential zone but now

we have universities, schools, offices, hospitals, clinics,

supermarkets and what not.

The plan

also had proposals for rapid transport like shuttle trains,

flyovers but nothing was done. So the main problem is the

implementation of the plans.

Rajuk

is the authority that gives permission when we make a building,

be it an office building a house or a commercial facility.

If they are the sole authority, then no one should have been

able to build these commercial facilities in residential areas.

So they have failed in their main responsibility.

Architects

design the apartments but the owners are more interested in

how many flats they are getting.

We can't

blame the developers because it is their business. We are

all partly responsible. We are working with limitations. If

people don't want to keep open space, we designers can't force

them.

Say in

Dhanmondi when you make a six-storied building, you have to

leave five feet from front, four feet from the sides and about

six feet seven inches from the back. When you leave that amount

of space and make a building, it is just a box that comes

up. You don't have any space for plans, you don't have any

space for trees. So it is up to the Rajuk to make bylaws so

that people are bound to keep open spaces.

Fortunately,

Rajuk is planning on changing the by-laws and the Institute

of Architects, REHAB and Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon are working

together to make those by-laws more environment-friendly.

Rafiqun

Nabi: I will put the blame of jerry-building on the

concerned authority including RAJUK, City Corporation and

the ministries connected to town planning and maintenance

of cleanliness and shape of the growth of the city. These

people in power are just not sincere. The experts at the helm

of affairs appear to be somewhat callous. Behind the evil

that faces us is malpractice. Again there is the matter of

inadequate funding while whatever is available is misused.

Architects

too, although they are talented, sincere and hard working,

don't get the perfect connoisseurs of architecture to drive

them on. It isn't necessarily true that the owners of the

estates and buildings have good taste: they try to compel

the architects to go according to their will. They make the

architects toe the line of what they've seen in developed

Far Eastern cities such as Singapore or Bangkok. A lot of

construction in Dhaka is a copy work of what is seen abroad.

The owners are carried away by the façade rather than

the utility value. They forget about the amicable relationship

with neighbours or have little concern for the adjacent roads

and lanes.

Authorities

like WASA and the Dhaka Municipality moreover, have no co-ordination

between. Someone cuts a road; another comes and lays pipes

along the road yet a third party comes to finish the job plus

they have anomalies at work there. Authorities

like WASA and the Dhaka Municipality moreover, have no co-ordination

between. Someone cuts a road; another comes and lays pipes

along the road yet a third party comes to finish the job plus

they have anomalies at work there.

If one

considers town planning in Athens, where I was educated, and

other well-planned cities in both the East and West -- both

old and new I found more harmony. Doxiadis, who has designed

some of the Dhaka buildings such as TSC, The Home Economics

College, and BARD in Comilla, compelled our government to

follow his plans, rules and regulations. He made high-rise

buildings despite having the Athens Acropolis with a few kilometres

and nothing appears out of place. The old and new mingle together

and could easily emulate such town planning in our own capital

city.

Ataus

Samad: The first guideline of city planning was completed

in 1959 and subsequently it was revised in 1995. The 1995

plan was an UNDP-funded project. Foreign planners came and

stayed in Dhaka for years.

This planning

was just a guideline for the development of a city. Subsequently

what was expected of the Rajuk was development of the city

according to that guideline, detailing out roads, walkways

and open areas but that detailing was never done. It was just

a guideline plan and Rajuk was supposed to get it done either

by itself or through local consultants. They initiated the

process at one point but nothing happened after that.

The other

problem is that if a city does not grow according to a guideline,

then the whole system gradually collapses. Political interference

happens everywhere but here it has descended to the level

of greed.

The government

can tell a garment factory owner to go and set up an industry

for workers outside Dhaka. The incentive here will be that

money would be made available to him for the purpose at a

very low interest and it will be a long-term loan for say

40 years. The moment the government can give that kind of

assurance, that is when it can ensure a solution for the problem.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|