Human Rights

A Respite from the Nightmare

Aasha Mehreen Amin

|

| Sandra Longley. PHOTO: Zahedul I Khan |

Twenty-six year-old Sabina Akhter did not get a chance to learn enough English so that British police could understand the gravity of her situation. She had to die at the hands of her psychotic husband Malik Mannan, a British Bangladeshi, who had assaulted her on at least twenty occasions during their marriage before finally stabbing her to death with a kitchen knife in front of their 3 year-old child. While one may think that domestic violence is more common among Asian communities, the truth is that it is a universal problem and even in a developed nation as the UK, where two women are killed each week by their husband or partner, many of the victims are white. While the stories are shockingly gory, a glimmer of hope is being provided by individuals who have dedicated their lives in trying to save the lives of women like Sabina. Sandra Longley, the chief executive of Refuge the first and now largest serving organisation for victims of domestic abuse in the UK, has been working with abused women for over 32 years. On a recent visit to Dhaka, Sandra, who has received numerous accolades including the OBE (Order of the British Empire) for 'services to the protection of women and children' shares her experiences as an activist in the UK as well as her impressions of how this malaise is being addressed by Bangladeshis.

Sandra's first experience with dealing with abused women was when she took up a job to head a charity called Haven Project in Wolverhampton in the late 70s that provided shelter to such women. "For the first five years," says Sandra, " I was the only permanent staff member and I admitted 3,000 women to the shelters during that time." Sandra, a Canadian-born who decided to stay on in the UK after completing her degree from Birmingham University, started working with homeless women, Asian women trying to avoid forced marriages, mentally ill women, sex workers, substance abusers, abused women and children who comprised two-thirds of the shelter inmates. It was the late 70s and domestic violence was not a common term for what people considered a personal, 'family matter'.

"I was shocked at the level of brutality", recalls Sandra, "In the first case that I had to deal with, it was a woman whose face was a mass of purple bruises and 250 stitches. Her jaw was broken in five places and her nose was broken. I had to feed her with a straw. When I asked the police what had happened to the man, they said: "Oh it's a domestic issue, the police have nothing to do with it."

Sara begged to differ and believed that domestic violence was a public issue, a breach of human rights, and a crime. Thus even in the early days Sandra was already battling with the authorities to treat domestic violence as seriously as any other violent crime.

|

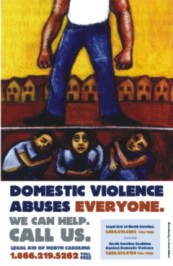

| Source: www.legalaidnc.org |

"It took several decades for police to change the practice of the police", says Sandra, "to recognise it as a crime." Unfortunately, for Sabina Akhter, even though the police did eventually arrest her husband after taking her allegations seriously, they were not able to prevent him from killing her. Malik had been set free on bail with the condition that he would not go to Sabina's home or harass her. According to Sandra whose organisation Refuge, has decided to sue the Manchester police, the police did not do enough to save her. If she wins it could become a test case so that police everywhere in the UK will be more vigilant and conscientious about such situations.

In 1983 Sandra's work took a new turn when she took charge of a project called 'Refuge', an organisation that started with one house to become the largest single provider of domestic violence services. In any given day around a thousand women come to the shelter for help. "We don't have enough bed space for all the women who come to us. So we set up community centres for particular communities such as for African, African Carribean, Eastern Europe, Asian , Portuguese and other ethnic minorities. We have bilingual staff who speak their language, wear the ethnic clothes and blend into the community. Before you know it, women will come up and admit they are being abused and these women get help to escape."

Her work made Sandra realise the trauma that the children of these victims also went through. 9 out of 10 cases of domestic violence, the children are in the same or next room. "The children lose concentration in their studies, they are withdrawn and get very depressed. Many women and children experience post-traumatic stress because they have gone through such trauma, it is like being in a car crash."

Refuge has a team of independent domestic violence advocates who help these women to get 'protection orders' under the Domestic Violence legislation. Such an order could be a court order for the perpetrator to leave the house so that the woman can stay in safety, to stop harassing her or stay away from her. The reality says Sandra, is that sometimes men breach the orders and go back to abusing their wives or girlfriends.

"The independent advocates", says Sandra, " go to give evidence against the men. If the man is prosecuted they need to call the woman to give evidence and it is very difficult for a woman to give evidence against her husband, someone she had loved and trusted the most. Sometimes the advocates speak for them, they may ask for a screen in the courtroom or permission for the woman to give evidence through a video or a separate waiting room." "The independent advocates", says Sandra, " go to give evidence against the men. If the man is prosecuted they need to call the woman to give evidence and it is very difficult for a woman to give evidence against her husband, someone she had loved and trusted the most. Sometimes the advocates speak for them, they may ask for a screen in the courtroom or permission for the woman to give evidence through a video or a separate waiting room."

Sandra says that the number of prosecutions has increased. "This is isn't about being anti-men. It is about saving lives. Sometimes it helps the men because if they were not stopped they would have gone and killed their wives."

Domestic violence, says Sandra, destroys the family and the social fabric of society. "If women and children are beaten at home children can't concentrate in school, women have to call in sick frequently, so industry suffers too. Domestic violence costs the UK 20 billion pounds a year and this includes the legal costs (arresting, charging and prosecuting the perpetrators), legal aid bills, re-housing costs children's home costs, medical costs (to patch up a woman's face); so it is a huge expense to the state on top of all the human misery."

While organisations like Refuge literally save lives as well as play important roles in providing psychological support to victims and their children, advocacy and lobbying for policy and legislative changes, Sandra insists that there is so much more to be done in terms of educating people, early interventions such as teaching children about relationships based on equality and respect and dealing with frustration without resorting to violence.

"Another thing we did is give out these cards to young women that identify some early warning signs to look out for before they get too involved in a relationship" says Sandra. "From research it has been seen that some of the signs that a partner may become abusive include: extreme jealousy and possessiveness, isolating the woman from family and friends, volatile behaviour such as changing from being charming to suddenly violent, using anger to intimidate such as smashing furniture, killing pets and so on. There was a woman whose husband had thrown the dog out the window from the 17th floor. The message was: It could be you next." Domestic violence says Sandra, has a pattern; it is systematic. "Many men grow up thinking they have a right to hit women because the society tolerates it and there is nothing to stop it, so they grow up thinking it is acceptable. Men have a role to stop it because it is something that is damaging all of us.

Sandra's short visit to Bangladesh, she says has been enlightening. "I was alarmed by the very high prevalence in Bangladesh. In a survey conducted by ICDDRB in 2001 (attached), about 60% of the sample of over 3,000 women of reproductive age in Bangladesh reported having been physically or sexually abused by their partner. This makes Bangladesh a country with one of the highest rates of domestic violence in the world. Bangladesh is also one of the only countries in the world in which the suicide rate among women is higher than among men. And there is a close correlation between domestic abuse and female suicide."

Sandra visited a number of shelters for victims of abuse, and spent time with international aid agencies, lawyers and NGOs, including the Bangladesh National Women's Lawyers Association (BNWLA), Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) and Oxfam, who are conducting an awareness-raising campaign - the 'We Can' initiative that has motivated half a million chain-makers (half of whom are men) to spread the word that domestic violence is an unacceptable crime.

"Time and again I was struck by the complexity of the difficulties facing victims of domestic abuse in Bangladesh" says Sandra. "It is a myth that only poor women in rural areas of Bangladesh suffer from domestic violence; it affects the wealthiest too. But the poorer a woman is, the harder it is for her to escape from an extremely dangerous man. She is dependent on him financially, and so are her children. Frequently the woman's own parents and siblings want to help her escape but they simply cannot afford to rescue her, and so she has to endure extreme violence. Many of the people I met this week emphasised the need for more Bangladeshi women to be able to earn a living to enable them to escape abuse.

Sandra also met with the Minister for Women and Children's Affairs, Dr Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury and was impressed by her pledge to push the domestic violence bill through parliament in January. "The bill is far-reaching" comments Sandra, "and includes the recommendation for a help line and a guarantee that men who have been arrested for abusing their wives will not be granted bail for at least three months, to ensure that their wives and children have time and space to plan for their safety."

This new law while a major breakthrough, cannot, by itself save lives, says Sandra. It is crucial that it is combined with a realistic implementation plan with appropriate levels of funding. People need to be educated about the disastrous effects of domestic violence on society to prevent it she believes; abused women and children have to be provided shelters, there should be helplines; they must be protected by arresting the offenders and victims must be offered civil remedies and legal aid. All this has to be done simultaneously along with the new law.

.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |