|

||||||||||||

Thoughts on Victory Day- Shamsuddin Ahmed People in people's war- Abdul Mannan A forgotten hero of 1971- Lt Col (retd) Foyez Bahar Global response to our War of Liberation- Muhammad Zamir Daring escape to freedom- Abdullah Dewan and Ghulam Rahman Recounting a perilous journey- Barrister Harun ur Rashid Freedom fight by two missionaries- Shahnoor Wahid How victorious is our Victory Day?- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Liberation War 1971: Geo-political fallout-Air Cdre (Retd) Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury

|

||||||||||||

| People in people's war

Abdul Mannan Nissar Allana was a young intern in a Bombay Medical College in 1971 when Bangladesh's War of Liberation was nearing a turning point. By the month of August the monsoon had receded and the Mukti Bahini was controlling a large portion of Bangladesh. The desperate Pakistani marauders, after taking a good beating from our valiant freedom fighters pulled back to their barracks in towns and cities and unleashed a new wave of terror on unarmed civilians. A new wave of refugees began their miserable and dangerous trek to neighbouring India, especially West Bengal. The refugee camps across the border were overwhelmed. The world media refocused their attention on our War of Liberation and developments in the sub-continent and intensified their campaign to help the suffering millions. Nissar went to his college Principal and asked his permission to take a team of volunteer intern doctors to help the Bangladeshi refugees, hundreds of miles away from the bustling city of Bombay. How could anyone not heed to such a request? Recently Nissar was in Dhaka to participate in the Fourth International Ibsen Festival. Though he is a trained physician by profession now Nissar is a Scenographer and runs his own The Dramatic Art & Design Academy (DADA) in Bombay. While we sat in a Five Star Hotel's Swimming pool side dining area and struggling with our tough tandoori nan on a warm and humid autumn evening this November. Nissar became emotion chocked while narrating his experience of 1971.

Though the Principal was very generous in giving the permission to Nissar to go and help the refugees he needed fund to buy medicine and for travel and stay. The Bengali community in Bombay was very generous and so were others. He got his friends to collect the money, buy the medicine and one morning left Bombay for Calcutta along with five of his volunteer friends. Bombay to Calcutta is a long journey by train. It took them about a day and a half to reach Calcutta. Practically for all of them Calcutta was a new city and the spillover of refugees into the city was starkly visible. Spending a night in a friend's house Nissar and his team headed for Gede refugee camp across our Darshana border, one of the most miserable camps, sheltering some half a million refugees. The abandoned Gede station served as a base camp for many volunteer groups. What Nissar and his team saw was just unbelievable. How could one deliver a baby under an open sky, next to a train line, while the bay's father a day labourer by profession was fighting inside Bangladesh to reclaim his country? However challenging the task was, Nissar and his team members struggled to show the new born the light of a new world however cruel it was. I could see Nissar's watery eyes while he narrated these forgotten tales of heroism and bravery. The waiter brought us some more freshly baked nans. Nissar was no soldier and carried no guns. He was an ordinary man along with millions of others on both sides of the border who fought their version of our Liberation War. They were the common men, often the unsung heroes. A war to many means only firing guns and throwing bombs by the trained soldiers of two or more sides. However, historically no war for a country's independence was ever won without the active participation of the general masses, the common people and your next door neighbor. History, unfortunately often forgets the heroism and sacrifices of these brave people. An important flash point in our history of independence was March 1, 1971, when General Yahiya unilaterally suspended the sitting of the first session of the National Parliament giving in to the conspiratorial demands of Zulifiqar Ali Bhutto, the Leader of the minority party. The first protests came from the common people of the street at Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi and other cities and towns of the country, the students being the driving force of the protests. On the fateful night of March 25, just before the 'Operation Search Light' was put into operation by the Pakistan army to annihilate the Bengali people it was the common people who offered the initial resistance by putting barricades on the streets of Dhaka and Chittagong. They were the common people of the street, the rickshaw pullers, the day labourers, the retired government employee or the pavement dwellers. They were one of the first casualties of our liberation war, whose names are never recorded or sacrifices seldom recognized. From March to December, 1971 when our valiant freedom fighters were busy fighting the war in all fronts with arms and weapons the common people, putting their life and property at great risk, provided the much needed shelter and safe haven inside the country, infested in most places with Al-Badr, Razakars and the Pakistan Army. Not only they provided shelter and food to the freedom fighters, they brought in the important information of the enemy movement and arranged for much needed medical supplies. They were the unsung heroes of our liberation war. The kept the spirit and hope alive. Altaf Mia and Ezhar Master were two retirees in their mid sixties. Altaf Mia ran a small engineering shop while Ezhar Master sold groceries in Chittagong. One morning they were picked up by the Pakistan Army. Their crime was they secretly financed the local boys joining the Mukti Bahni. Both never returned while the family still waits. Quddus sold vegetables in the local bazaar. He not only carried vegetables from Sitakund to Chittagong, his vegetable basket also contained hand grenades for the Mukti Bahini. Just before he entered the city, the vegetable truck was stopped, the baskets searched and grenades found. Before Quddus was shot by the Army he was hanged upside down on a road side tree for couple of hours so that others could see and his body was left for a week to rot after he was executed. Abdul Baki alias Bocha Mia, whose passion was playing cards was never confused whether he was a Muslim or a Bengali. Baki never went to school. Family poverty had taken its toll. When asked by a gun totting Punjabi soldier if he was a Hindu, Mia without blinking his eyes said no, he was a Muslim but a Bangali Muslim. The shot from the gun totting soldier missed Bocha Mia's head, hit him in his right shoulder and he lay in a pool of blood for next two days till he crawled to safety. They were all our unsung heroes never received a decoration for their bravery. My mother was in her mid fifties when we went to war. Could not continue education after her primary level but had a very clear understanding why we bet our life in 1971. She sewed a 'Joi Bangla' flag in the first week of March and made us hoist on our roof top. After the crackdown on the night of 26th. the flag came down. For the entire nine months my mother carried the beloved flag she sewed in her waist with her sari, lest it falls into wrong hand. On 16th of December amidst all those euphoria of being a liberated country she did not forget to ask my school going younger brother to hoist the flag in the fading twilight though the guns in many places in Chittagong were still looking for innocent targets. My brother did and later went to become a professional soldier in independent Bangladesh. My mother in our eyes was one of the bravest freedom fighters around. The commoners' tales will not be complete if I did not mention about an Australian physician, Dr. Geoffrey Davis. He came to Bangladesh in the month of February 1972 on an invitation from UNFPA, Planned Parenthood International and WHO. His mission was to help the 'Birongonas,' Bangali women violate and compelled to bear child. Though most of these unfortunate mothers could not be helped as they were in their advanced stage of pregnancy, Dr. Davis could help many. He set up a hospital outside Dhaka with an office and a clinic in Dhanmondi. Not only he and his colleagues helped the reluctant mothers they also took care of many new born babies. Some of the tasks were neither easy, nor did he enjoy doing it. But he says it had to be done. In an interview given just before his death in Sydney, Australia, on October 13, 2008, Dr. Davis commenting on his work in Bangladesh immediately after the War, said 'I felt that Tikka Khan's programme (ordering his soldiers to violate Bengali women indiscriminately) was an obscenity, comparable to Heinrich Himmler's Lebensborn Ministry in Nazi Germany. It gave me some satisfaction to know that I was contributing to the destruction of the policies of West Pakistan.' Dr. Davis worked in Bangladesh till the end of August 1972 and then left for Australia, never to come back. As mentioned, the war of Liberation was not only a military expedition sometimes portrayed by vested quarters. It was a People's War. No people's war in history ended in success without the participation of common people. Majority of the people who went to war in 1971 were the common people. The peasants and workers. The common folks, who just loved their country. American War of Independence, China, Algeria, and Vietnam are testimonies of People's War ending in success because of general people's participation. Bangladesh was no exception. Nissars from across the border, Abdul Bakis inside Bangladesh or brave mothers in our homes or Geoffreys in a distant land are part of our history. They are the commoners whose many tales of valour and bravery will never be fully told. To them, our felicitations. The writer is a former Vice Chancellor, University of Chittagong. Currently teaches at ULAB.

|

||||||||||||

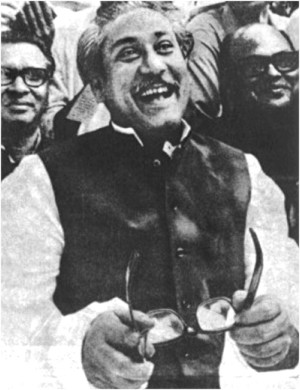

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman- the supreme leader of our liberation movement.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman- the supreme leader of our liberation movement.