|

||||||||||||

Thoughts on Victory Day- Shamsuddin Ahmed People in people's war- Abdul Mannan A forgotten hero of 1971- Lt Col (retd) Foyez Bahar Global response to our War of Liberation- Muhammad Zamir Daring escape to freedom- Abdullah Dewan and Ghulam Rahman Recounting a perilous journey- Barrister Harun ur Rashid Freedom fight by two missionaries- Shahnoor Wahid How victorious is our Victory Day?- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Liberation War 1971: Geo-political fallout-Air Cdre (Retd) Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury

|

||||||||||||

| Liberation War 1971: Geo-political fallout

Air Cdre (Retd) Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury The Liberation War in 1971 brought momentous changes in the regional and global geo-politics. Bangladesh was the first country since the end of WWII to have successfully gained independence from the federating state. The UN and its member states had accepted the inviolability of their frontiers in spite of many frontiers having been drawn by colonial powers disregarding popular aspirations. Thus, attempted bids of secession by the Congolese province of Katanga in 1960-63 and the Nigerian province of Biafra in 1967-70 had failed due to lack of international support. Especially in case of Biafra, it was apparent that most Biafrans supported independence and were willing to make enormous sacrifices for the same, but in the end they failed. Thus, while war for an independent Bangladesh started on 26 March 1971, despite popular support, external support was not easy to come by. In fact, all major powers, except India and at her behest the Soviet Union, had called for political solution within the framework of a united Pakistan. Many UN members were apprehensive that once precedence was set, it would encourage such movements in many parts of the world.

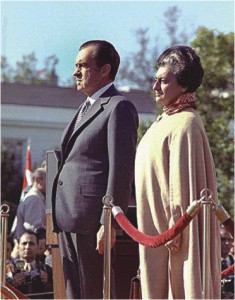

Global power-play at the time greatly influenced the turn of events in South Asia. It was at a time when the East-West “Cold War” was at its height. While Pakistan was a signatory to a number of military pacts with the US, nonaligned India was tilted towards the Soviet Union in its external relations. By mid-1960s, the Sino-Soviet rift had so widened that China was trying to warm up relations with the US. Pakistan, as a common friend of both the US and China, was acting as a go-between in restoring US-China relations that had soured since the communist takeover in China in 1948. While the Soviet weapons poured into India, China emerged as a major supplier of military hardware for Pakistan. As the war cloud gathered in South Asia from March 1971, the USA and China came clearly in support of Pakistan, while the Soviet Union lent its support for India and the cause of Bangladesh. The US administration viewed political upheaval in the Bangladesh (East Pakistan) as Pakistan's internal matter and considered India's clamour for international intervention as undue interference. President Nixon feared that dismemberment of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh would mean preeminent role of Soviet Union in South Asia and would undermine the US position in the Indian Ocean region. Although there was widespread support for Bangladesh among the Americans, Nixon took a strong pro-Pakistan stance. The Chinese too feared that Soviet domination of Asia would further isolate them and decided to checkmate Indo-Soviet moves. Pakistan was able to convince the Gulf Arab states that Bangladesh movement was an Indian attempt to weaken the largest Islamic nation and would put Islam in danger. Pakistan was so emboldened by the support from the United States, China and the Gulf Arab states that President Yahya Khan threatened all-out war on 1 December 1971 and had launched pre-emptive air strikes against India the next evening. Over the next few days, however, the Indo-Bangladesh joint forces had overwhelmed the Pakistani forces in the east. Pakistan had suffered serious reverses in the western front too. India recognized Bangladesh as a sovereign state on 6 December 1971, followed by the Soviet Union among others. As the total defeat of the Pakistani forces in the east became apparent, Nixon administration was worried of a possible Indian thrust into Western Pakistan. As a preemptive move, President Nixon ordered a Task Foce led by the nuclear-powerd aircraft career USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal. The Task Force arrived on station on 11 December 1971. As a countermeasure, the Soviet Navy dispatched two groups of ships from their eastern fleet, armed with nuclear missiles and also a nuclear submarine to trail the US Task Force. Suddenly, the limited war in South Asia apeared to turn into a global confrontation with nuclear dimension. However, unconditional surrender of the Paksitani forces in Bangladesh on 16 December, unilateral declaration of ceasefire by India on all fronts on the next day and public pronouncement by Mrs. Indiara Gandhi that India had no territorial ambition, quickly dissipated tension. By mid-January 1972, both the Super Powers had withdrawn their forces from battle stations.

With a popular democratic government installed in Bangladesh, international recognitions were quickly pouring in. However, China and Saudi Arabia, at the urging of Pakistan, did not recognize Bangladesh. On 25 August 1972, China vetoed an initiative made by the USSR and India for the UN membership of Bangladesh. China that had been kept out of the UN for a long time denied the right of admission of Bangladesh, another independent state. Pakistan recognized Bangladesh in 1974, but the Chinese recognition came only in 1976 and only then Bangladesh could become member of the UN. On the strategic front, India lost an opportunity to wrest a settlement on Kashmir when she had nearly 90,000 prisoners of war (POW) and controlled a large chunk of Pak territory. In the Simla Agreement signed on 2 July 1972, Mrs. Indira Gandhi gave away too much for too little. Pakistan got back all the lost territories, except for small pockets in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Soon the POWs too were handed over, including those who were accused of war crimes by Bangladesh. In fact, Pak Prime Minister Z.A. Bhutto of Pakistan could later claim victory over India in the negotiating table. Meanwhile, trying to seek a new national identity, Pakistan tilted more towards Islam and the Middle East. The new generation of Pakistanis considered themselves more a part of Central and Western Asia rather than of South Asia. As religion came to dominate more and more of the political, economic and social life, serious cleavage appeared within the Pakistani society. The first was in 1973 by Mr. Bhutto declaring the Ahmediya community as non-Muslim. Soon there were other issues, such as Shia-Sunni conflict and the Intra-Sunni clash between the Wahabi and Brelvi schools. Whatever was left of the socio-political modernity ended with the Islamisation programme of President Ziaul Haque (died 1988). If the signatories in Simla were hoping for an era of friendly relations between India and Pakistan, they were sadly disappointed. The relationship never warmed up beyond occasional thaws. The gap in conventional military capabilities between India and Pakistan further widened. Pakistan sought to close the gap by opting for nuclear weapons. India's “peaceful nuclear explosion” in Rajasthan in 1974 further hastened Pakistan's search for a nuclear option. By 1980s, it was generally believed that both India and Pakistan had nuclear weapons. What was speculative, finally surfaced with India and Pakistan both carrying out nuclear tests in 1998. For the first time, the world had two nuclear neighbours with a history of wars between them; the stakes suddenly became very high indeed. If India was hoping for a perpetually tranquil border on the eastern front, her hopes were short-lived. With the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in August 1975, the new regime in Bangladesh sought to rejuvenate relationship with Pakistan, China and the Arab world, and took an anti-Indian, anti-Soviet stance. While the Indo-Soviet influence waned, those of Pakistan, China and the Gulf Arab states waxed. Secularism was replaced with Islam as the state religion. Like Pakistan, a process of Islamisation of the society and state started. While Bangladesh kept blaming India for sheltering insurgents from Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), India routinely accused Bangladesh of aiding and abetting secessionist elements in the NE Indian states. Indo-Bangladesh Relation dipped further due to the commissioning of Farakka Barrage and withdrawal of waters by India from many common rivers. Although much progress was made through SAARC, the Indo-Bangladesh friendship and cooperation, as envisaged in 1971, remained a mirage. The process of Islamisation in Bangladesh resulted in the growth of Islamist parties, and in their wake grew Islamic militant organisations of various hues. Although in the election held in December last year people voted overwhelmingly for secular democracy, the character of the state continues to be tied to the past. The dreams of those who fought for an independent, prosperous, secular and democratic Bangladesh largely remain unfulfilled. The nine month long war for Bangladesh left a lasting impact on South Asia and the world. It not only changed the map of the region, it forever changed the power equilibrium. Long after the guns fell silent and the warriors went home, the geo-political impact of the war continues to evolve and reshape. The writer is a security expert.

|

||||||||||||

The ceasefire came into effect on all fronts by the evening of 17 December 1971. While Bangladesh emerged out of the war as a new nation, the end of war set about a new equation in the regional and global power play. India emerged as the pivotal power in the region, in size and population, in economic and military strength. Pakistan seemed to have lost its ideological mooring as the majority population in its eastern wing discarded the “Two-Nation Theory”. Liberation of East Pakistan proved that religion alone was not a sufficient binding element. One positive outcome of the war was the restoration of democracy in Pakistan; military having lost its face in the war handed over power quickly. However, those hoping for a federated Pakistan were disappointed when military forces were deployed in 1973 against Baluch nationalists demanding greater regional autonomy. The military actions against the Baluchis are continuing even today, much of it outside the world scrutiny.

The ceasefire came into effect on all fronts by the evening of 17 December 1971. While Bangladesh emerged out of the war as a new nation, the end of war set about a new equation in the regional and global power play. India emerged as the pivotal power in the region, in size and population, in economic and military strength. Pakistan seemed to have lost its ideological mooring as the majority population in its eastern wing discarded the “Two-Nation Theory”. Liberation of East Pakistan proved that religion alone was not a sufficient binding element. One positive outcome of the war was the restoration of democracy in Pakistan; military having lost its face in the war handed over power quickly. However, those hoping for a federated Pakistan were disappointed when military forces were deployed in 1973 against Baluch nationalists demanding greater regional autonomy. The military actions against the Baluchis are continuing even today, much of it outside the world scrutiny.