|

||||||||||||

Thoughts on Victory Day- Shamsuddin Ahmed People in people's war- Abdul Mannan A forgotten hero of 1971- Lt Col (retd) Foyez Bahar Global response to our War of Liberation- Muhammad Zamir Daring escape to freedom- Abdullah Dewan and Ghulam Rahman Recounting a perilous journey- Barrister Harun ur Rashid Freedom fight by two missionaries- Shahnoor Wahid How victorious is our Victory Day?- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Liberation War 1971: Geo-political fallout-Air Cdre (Retd) Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury

|

||||||||||||

| Recounting a perilous journey

Barrister Harun ur Rashid By 1969, Bengali foreign service officers posted abroad were being transferred pre-maturely to the Pakistan Foreign Office in Islamabad. During this time I was in the Pakistan Foreign Office and lived in Islamabad with my family. I went to New York in 1969 and after my return to Islamabad in January 1970, there was a feeling in Pakistan, mostly among Punjabi officers, that sooner or later East Pakistan would secede from Pakistan. They perceived that “East Pakistan” would learn its “lesson” by being independent. The election in November 1970 made us hopeful that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would be the Prime Minister of Pakistan and at one stage, military President General Yahaya Khan acknowledged this fact to the media. We expected that the talks that started in Dhaka during March 1970 would reach a compromise but our hopes were cruelly dashed when we learnt that Bangabandhu was arrested and flown to West Pakistan. All Bengali officers realised the dire consequences that would follow the arrest of the most popular Bengali leader. Little did we realise in Islamabad that the military junta would be so brutal and ruthless in launching a military crackdown on the innocent unarmed Bengali civilians on the 25th March 1971, in Dhaka, constituting genocide and crimes against humanity. We did not know what actually happened in Dhaka on 25-26th Mach as the media in Pakistan provided us sanitised version of the horrible events in such a way as if nothing had happened except arrest of a few leaders and their supporters in “national interest”. Z.A. Bhutto described the military crackdown with his infamous comment “ Thank God! Pakistan is saved.” We suspected the Pakistani version of events and began listening to the news broadcast of All India Radio and BBC for correct news and this practice continued until the surrender of Pakistani troops in Dhaka on 16 December, 1971. I was deeply concerned about my near and dear ones, in particular about the fate of my elder brother, Barrister Kazi Ahmed Kamal who was very close to Bangabandhu. They were friends as they were together in the Baker hostel in Calcutta as students during 1942-44. ( After independence, my brother was the first Bangladesh Ambassador to East Germany in 1972). I found out later that all my close relatives including my brother fled Dhaka and went to our paternal village in Vikrampur, about 20 miles from Dhaka city. We, the Bengali officers, were the employees of Pakistan Central Government and since the capital was in Islamabad, we were there. When Bangladesh became independent we all wanted to return and serve the new country. But the then new President Z.A. Bhutto did not allow us to do so and declared to hold us hostages in Pakistan until the return of Pakistani prisoners of war from India. We were shocked to note that Bhutto equated us- Bengali civilian officers- with those of prisoners of war. We were given an option to serve Pakistan or “so-called Bangladesh”. We objected to the words of “so-called Bangladesh” and “option” because our return was not an option but a compelling fact for our homeland independent Bangladesh--where our ancestors lived and died. When we exercised our “options”, our services were terminated immediately.

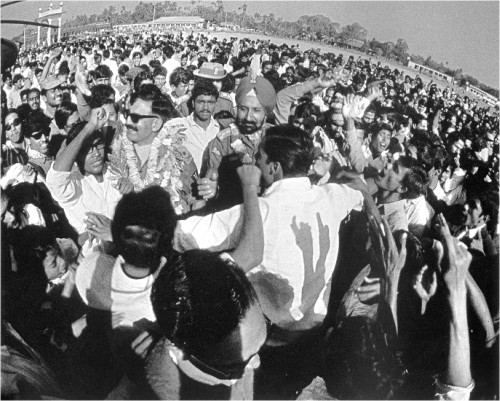

We soon learnt that we would be sent to camps (concentration camps) outside Islamabad and would remain there until the issue of repatriation of Pakistani prisoners of war was resolved. We did not know how long we had to live in the camps in Pakistan with restricted movements and when we would be released from the hostage situation. Escape from Pakistan to Bangladesh Meanwhile we sold our personal goods such as car, fridge and air conditioners to sustain ourselves. We soon learnt some bachelor Bengali officers had escaped from Pakistan via Kabul and we thought about it. But the difficulty was that my wife and I had a young family of three. The eldest child was 6 years and the youngest was barely two. My wife, Najma and I had to think twice as to taking a recourse in escaping with small three children because we needed complete secrecy and silence in the transport we would take to Kabul from Islamabad via Peshawar and tribal areas. Our main considerations revolved around three factors how would the children handle the escapade? Would we be able to keep them quiet during the trip as the slightest noise from the children would involve risks (arrest and jail)? How safe would be with unknown people who would organise the escapade? Our confidence was strengthened when one of my friends with his young children and wife were successful in reaching Kabul. He directed us to a group of Peshawar University students who agreed to organize our escape in exchange of money in cash. My wife and I met with them at a local cinema so that nothing looked suspicious with their company. We were allowed to take one small suitcase during the escape and the arrangement was that we would go to Peshawar on our own from Islamabad and we would be picked up by a car (registration number was given to us) at the railway station and thereafter we would be transported by trucks/car to Afghanistan crossing the border at Torkham via Khyber Pass. We had to pay half the money to them and the rest would be paid when we reach Afghanistan. That seemed to be fair deal to us. We left our house in Islamabad (House 81-H type house, F-6/3 sector) early in the morning leaving our sofas, curtains and other furniture in the house, so that no one in the neighbourhood would suspect anything unusual. We took a taxi first to a residential area in Rawalpindi so that the taxi driver would think that we had come to visit a friend's house. The residential area was inhabited by West Pakistanis. Then we took another taxi from the residential area to the railway station of Rawalpindi. We were dressed in Pakistani style-Shalwar and Kurta or Kameez. We took a third class compartment to avoid any friend or acquaintance on the journey. We also behaved as if my wife was a stranger and a separate passenger. She was dressed in such a manner that she could be easily passed as a Pathan woman. I also could be identified as a Punjabi or Pathan. Since my Urdu was not good, I pretended to sleep when any one was near to me. On our way the police checked each compartment of the train to detect any Bengali passenger. However, they checked our compartment and left us undisturbed. We arrived at the railway station in Peshawar and found the car with the given registration number waiting at the station. While we quickly got into the car, a man followed me and I thought that we were caught in the escape plan. Little did I realise the man was a ticket collector and I forgot to handover tickets to him in a hurry as I was too anxious to get into the car. The Pathan driver drove very fast and crossed two checkpoints manned by security forces on way to the tribal areas. I felt that they were bribed beforehand so that they let us pass easily through the checkpoints. After a good 45 minutes drive, we arrived at an open big yard surrounded by high mud walls with mud- shed in one corner meant for donkeys. The location of the site would be near the entry of Khyber Pass. We now realised that the Peshawar students handed us over to tribal people who had covered their faces with Chaddor and we only could see their eyes. We thought that the Peshawar University students would accompany us all the way but that was not the case. And we were deeply worried that we were at the mercy of the tribal people in the tribal areas which were not subject to ordinary laws of Pakistan. We were led to the donkey's mud house to stay until their further advice. We were pleasantly surprised to meet with a few other Bengali officers with their wives inside the mud hut. We almost froze in shock when we learnt that the guard who took care of us was a convicted murderer and he escaped to the tribal area from settled areas of Pakistan. We were terribly worried to find ourselves in the custody of a convicted murderer. The donkey-shed where we were accommodated was dirty and smelly. There was a pitcher for drinking water where a frog was lurking in the water. We could not drink water from the pitcher. The guard could not get soft drinks for us from shops in settled areas because he could be arrested. However we managed to get soft drinks through another person. We were mentally and physically distressed. We had to spend day and night for almost three days in the donkey-shed. On the third day at 9:00pm, we were advised to get ready to move onwards to Landikotal that was well known as smugglers' market in the tribal area. Two huge trucks came and we had to climb through a ladder to the top of the truck. Below us were two levelsthey were filled with molasses and vegetable ghee in boxes to be transported to Afghanistan. We sat down on the top of the truck where we were covered by a huge tarpaulin so that no one could see us from outside. Simply put, we became “human commodities”. We arrived at mid night at Landilkotal and were taken to a house. We sat on the floor covered by a white sheet. We were subject to lengthy sermons from them until they finally hinted that they needed money from us to enable them to help us in the risky jobs. We handed over money to them and the final leg of journey began. We administered sleeping medicines to my younger children to avoid any noise from the truck. The border opens at six in the morning every day. Our trucks came at the border in the early morning but the men who were bribed at the check post were not present and my small children began to awake. The effect of the sleeping medicine we administered earlier to our children was almost at an end. We were worried that any slightest noise from the top of the truck would land us in jail. My wife had to administer again sleeping medicine to my youngest ones so that they kept quiet. The driver, sensing that the delay at the border was very risky, put the music of the car radio at its loudest volume that would minimise the risks of any noise, such as baby-crying, or coughing or sneezing. At Last in Afghanistan Our trucks halted at Jalalabad and a microbus came to take us to Kabul. At that point of time, we could see the faces of Pathan men who accompanied us. They were in their late thirties and wearing black beards. We paid half of the money to them. We were taken straight to a hotel. We waited three weeks in Kabul to get the Afghan air to New Delhi and then to Calcutta. Finally we landed in Dhaka by Biman. I joined the Foreign Office in Dhaka next day. In Retrospect The university students I had contacted initially disappeared from the scene with money and we never saw them again. It was like a relay race and we were transferred from one group to the other in tribal areas and they could have done immense harm to us, in particular to my wife. Our escape would not have been necessary if Bhutto's government was fair and decent. By all accounts, the Pakistan government should have allowed us to return to our homeland. By not doing so, we lost all our possessions, had to spend money (about Pak Rs. 20,000) for the escape and were put to extreme discomfort and anxiety, in particular my wife had to deal with three young children in an unfriendly and harsh environment for a month. I will never forget this extraordinary episode of our escape with my wife and children. This is another perspective how the War of Liberation affected Bengali employees of the central government stationed in Pakistan. The writer is former Bangladesh Ambassador to the UN, Geneva. |

||||||||||||