|

||||||||||||

Thoughts on Victory Day- Shamsuddin Ahmed People in people's war- Abdul Mannan A forgotten hero of 1971- Lt Col (retd) Foyez Bahar Global response to our War of Liberation- Muhammad Zamir Daring escape to freedom- Abdullah Dewan and Ghulam Rahman Recounting a perilous journey- Barrister Harun ur Rashid Freedom fight by two missionaries- Shahnoor Wahid How victorious is our Victory Day?- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Liberation War 1971: Geo-political fallout-Air Cdre (Retd) Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury

|

||||||||||||

| Daring escape to freedom

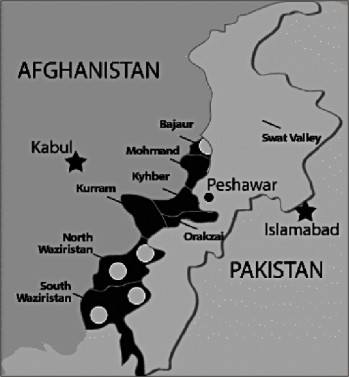

Abdullah Dewan and Ghulam Rahman As ill luck would have it, we both ended up in a quagmire at the same time in Islamabad during the war of liberation. So, we decided --why not narrate our stories in unison? However, reminiscing the experiences and events that happened 37 years ago (1970 72) solely from cognitive diaries at first seemed utterly improbable until a self-induced state of hypnosis triggered a flashing back of almost everything as if they all happened yesterday. During the war of liberation, having been stranded in Pakistan, we endured enormous mental agonies and anguishes but they were miniscule in magnitude compared to what the people back home had to withstand the despicable brutalities and humiliations inflicted by the barbarous Pakistani army. We therefore, skip most of that part of our experiences. However, our predicaments were fast worsening --from December 3 when the Indian army joined the freedom fighters-- and reached their nadir on December 16, once the news of surrender of the Pakistani army was broadcast. My perilous escape: Ghulam Rahman With the news of the surrender of the Pakistan army, extreme commotions and anguishes around the place of my residence and Several days later, after receiving a letter from me, Abdullah showed up in my residence and I felt somewhat strong-willed again. A week later, I moved with him to Islamabad and was commuting to my training academy from there. Our times were passing amid increasing apprehensions and uncertainties. Sometime in February, 1972, I was terminated from service once I exercised my option to return to Bangladesh. Once out of work, each hour felt longer than 60 minutes, and each day felt lengthened longer than 24 hours. Living in Islamabad was slowly becoming tense and tortuous -- somewhat life threatening, if you will. There were rumors about moving all Bengalis to concentration camps for swapping with the surrendered Pakistani army. Reports of frequent incidences of harassments and assaults became routine. Both of us were shouted at with name callings and subjected to verbal abuses many times to provoke a fight. Once such incidents became widespread, all Bengalis began to accept the fait accompli of being captives, waiting to face some kind of reprisals. Many Bengalis failed in their attempted escape to Afghanistan with the help of smugglers and ended up in prison. Meanwhile, I also got somewhat restless to make my move to escape to Afghanistan. Fortunately, I found a senior colleague from my office, who was negotiating an escape deal with the smugglers. There were six of us in the group his wife and two children including a six months old infant, and servant. Given the option, Abdullah opted out of the escape move. From my colleague's residence in Rawalpindi in the early morning of July 13, 1972, we got into a large size car and after about 11 hours of ride, stopping for food and rest, and passing through a few check posts unimpeded, arrived at dusk at a town named “Parachiner” near the Russian border. We slept overnight at our agent's house under the blue open sky in 'Khatia”. The following morning, under the guidance of the agent and his men, we crossed a river with knee high water with strong current and arrived at a mud-built house. On arrival, we were confined in a room hiding from public view. Our new hosts served us tea and lunch. In the afternoon, a leading person visited that house and opined against helping us escape as being morally inhibitive. My colleague with his oratory skill convinced an assembly of villagers that as fellow Muslims, helping the distressed Muslims from Bangladesh escape were their pious obligations. After dinner, the village men assembled in the courtyard of the house and prayed for our safety and then four tailor-tractors with about forty men armed with guns got us on the tractors and accompanied us as they drove through the dried up river beds (mountain passes through which snow melt water reaches the rivers) to cross the border. After about two hours of rough ride, we were asked to walk the rest of the way. We walked about four hours up and down hill near Afghan border in no men's land and then suddenly our guide announced that we were well inside Afghanistan territory. The joys and jubilations on our face left no visible mark of the exhaustion and anxieties we endured since we started this perilous voyage from Rawalpindi four days ago. We walked a little further and stopped on a hilltop near a water-well. Being tired and exhausted, we quenched our thirst with well water and soon fell asleep on the hilltop. Next morning, two tribal men, riding on a Jeep came to pick us up. They fired a few shots from their pistols and assured us that we were completely safe from any harm from Pakistan. The jeep driver drove us to his house, a two story mud building well quite far off Pakistan border. He invited a few village elders to dine with us and following tribal traditions, food was served in a single bowl from which we all ate our dinner. Next morning he drove us to Bazaar-e-Khust and helped us rent a taxi to go to a provincial city “Gardis'. We had our lunch there and rented another taxi for our onward travel and arrived in Kabul after dusk. We then reported to the Indian Embassy. We are now bona fide citizens of Bangladesh safe, free and out of harms-way! My daring escape: Abdullah Dewan Having Ghulam living with me made those dark days of despair and misery much less desperate. Certainly we were a great support and solace to each other. Amid those monotonous and melancholic days, I always looked for something to use up my times. Somehow the beast in me the instinct of writing about the on going liberation war could not be suppressed by the fear of reprisal from any quarter. I wrote a piece of about 850 words mailed it to a weekly newspaper, (to my best recollection) named, “The Punjab Chronicle”. Much to my surprise, the article titled “The misconceived two nation theory” was published four days later. The article argued: Bengali liberation war in East Pakistan is a testament to the reality that a nation built on the premise of religion alone while ignoring the lack of homogeneity of language, culture, and social traditions is a misconceived theory. A week later, Ghulam and I went to the house of the editor of the paper. Once we opened the gate, we were attacked by a fearsome dog but escaped from being bitten once the dog's owner calmed it down. After we met the editor, I gave him a new article for publication. The theme of this piece was: Stop fighting, make peace, and live in friendship thereafter. Once we were relieved of all official duties, and the Bengali children were barred from attending school, I volunteered to teach physics to high school children of Bangladeshi community. The school was organized in residential houses and set up on several locations depending on children's grade levels, all within the proximity of less than a mile. That kept me busy for about three hours a day, three times a week. After Ghulam's escape in July, a few of us were looking for our passage to freedom too. Teaming up with a group of four families, one late morning in September 1972, we got into four large size cars and were driven to a tribal leader's house five hours (120 miles) later -- about 20 miles West of Peshawar. While travelling to the tribal area, we (all men and women) had to wear “burqa”, covering our entire body for obvious reasons. The drivers of the cars kept at least a quarter mile distance from each car to avoid arousing any suspicion. All the cars had to stop at check posts before entering the tribal area. Apparently, the driver had prior arrangements with check posts police and we had no problem crossing the gates. After arrival at the tribal leader's house, men and women were separated which raised some tensions momentarily. Our team leader unsuccessfully tried to convince the tribal head to keep us all together. Everyone calmed down once we saw that the women were sitting in the courtyard or walking around and the children were in their usual fidgety playing mood. After lunch we were served with tea and they offered us to try smoking “hashish” if we so desired. We are then advised to take a nap ahead of all night's walking through the arduous mountain tracks. Once darkness set in, we got into our cars and after 20 miles of ride, we were dropped on a narrow gravel road at the lap of a mountain. The two waiting “Bengali escapee” traffickers e (BETS) quickly walked us to disappear in the mountain trails where we were joined by two cave men waiting with four donkeys to carry our few belongings and if needed for the children to ride on. The two BETS armed with rifles lifted our spirit by assuring us that no harm will come our way as long as they were alive. That made us all nervous, as if such a mishap is not completely ruled out. What choice did we have but to trust them --marching forward was the only option we had for survivalif at all. Our expedition to the promised border crossing proceeded amid fear of the unknown. We were told that we must walk faster and non-stop to cross the border before sunrise to avoid hiding in the mountain bushes the entire day. Around mid-night, we were taken to a cave where we were served with tea and fruits and were allowed 30 minutes of rest after we complained how badly our legs were cramping. Walking through the narrow mountain trails up and down amid the genuine fear of stepping on snakes and being attacked by mountain animals or the cave men from any direction were totally eclipsed by our indomitable will to cross the border to freedom. After walking four more hours, we were guided inside a second cave alongside the foot of a mountain. We were told by the BETs that we already crossed the border and out of all harms-way. People waiting in the cave offered us water, tea, and snacks. We were asked to take rest for an hour until sunrise. As dawn smiled on us, we walked about a mile or so before being driven by taxis to a border town about eleven miles away. After having some breakfast there, we boarded a public bus and arrived at a bigger city two hours later. We had good lunch there and we were told that Kabul was only 85 miles away. We again boarded a bus and arrived in Kabul at dusk. We spent the night in a moderately expensive hotel and next morning reported to the Indian embassy. The feelings of escaping from harms and humiliations to being recognized as bona fide citizens of Bangladesh were indescribable and openly emotional. We won't blame the readers if our death-defying passage to freedom read like a fairytale or surreal if you will. The stories, however, may not read like fairy tales to those, who, before and after us, also braved the treacherous passage to freedom. After receiving our H.SC diploma from Comilla Victoria College, we both started in Dhaka University physics department and were roommates in FH Hall. After about two months later, one of us switched to economics. After completion of our masters' degree, one of us committed to public service and now at career's end now, chasing the untouchable “corrupticians”. The other, almost at will kept switched from physics to nuclear engineering and then to economics and finally settled in doing what he is now relishing the most one that he started doing in a crèche -- reading, learning, and writing. Abdullah Dewan is a Professor of Economics at Eastern Michigan University and Ghulam Rahman is Chairman of Anti Corruption Commission, Government of Bangladesh. |

||||||||||||

everywhere in Pakistan overshadowed everything else. Amid fear of retribution, I was visibly shaken up for my physical safety. Although, no one threatened me with physical harmbut fear and foreboding of the unknown kept building up to a point of near nightmarish proportion.

everywhere in Pakistan overshadowed everything else. Amid fear of retribution, I was visibly shaken up for my physical safety. Although, no one threatened me with physical harmbut fear and foreboding of the unknown kept building up to a point of near nightmarish proportion.