|

||||||||

From better governance to Din Bodol -- Rehman Sobhan National consensus and unity for change -- Dr. Kamal Hossain The state, culture and society -- Serajul Islam Chowdhury Extra-mile the ruling party has to go -- Dr. Syed Anwar Husain Political culture and its impact on governance -- Enam A Chaudhury Political party finance--Muzaffer Ahmad Women of Bangladesh: where are they? -- Nasim Firdaus Women's role in politics- Quantity and quality -- Sultana Kamal To combat violence against women-- Mahmuda Husain The case of local government-- Tofail Ahmed Withdrawal of Cases Where is the end--Dr.Sarkar Ali Akkas A challenge for political management -- Rounaq Jahan Right to information: Status of implementation -- Shaheen Anam Reforms for democratic consolidation -- Dr. Badiul Alam Majumdar Provenance of administrative reforms -- Dr. Saadat Husain Parliamentary committees Moving from form to substance -- Farid Hossain Politicial spell on bureaucracy -- Sadrul Hasan Mazumder Carrying forward the RTI -- Sanjida Sobhan Governance in the new millennium -- Mahbub Husain Khan Boycott culture crippling parliament --Shakhawat Liton Can we expect an effective ACC? -- Iftekharuzzaman Sycophancy is a two-way road -- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Three years since 1/11: Expectation vs. reality -- Syed Munir Khasru Police and politics -- ASM Shahjahan Leaky drainage infrastructure of the capital city -- Ershad Kamol Reducing the horrendous traffic congestion -- Dr. Charisma Choudhury Implementation of Dhaka city Master Plan -- Salma A. Shafi

|

||||||||

Women's role in politics- Quantity and quality Sultana Kamal

That women will play a critical role in politics, in fact is no longer a matter of discussion. Struggles and movements for women's rights over many decades have marked women's political empowerment as a high priority. These took place mainly because it became evident that unless women have the right and power to contribute in policy making and to legislate for themselves, they will have to wait and depend on others to do it for them. As long as women remained excluded from participation in Parliaments, from political processes, and therefore from making or amending legislation, they had to depend on male legislators' agreement to legislate in favour of women having the right to vote, to sit in parliament and to hold public office. This dependency on others' goodwill or agreeing to bring change to women's lives, as experience goes, failed to yield the desired results. For in most cases, the analysis of the position of women from the others' point of view, particularly informed by patriarchal values, lacked a holistic vision which led to fragmental, partial and monolithic attempts to remedy the disadvantage, discrimination and exploitation suffered historically by women. They failed to capture the multi-dimension of women's disempowerment. The nineteenth century witnessed the starting of women's struggle, mainly for economic liberation and for educational opportunities. Soon the realization came that without a strong voice in the decision-making processes, no matter how much income a woman earned or how highly she was educated, exploitation of and discrimination against women would not see its end. Rather, in many cases it was seen to widen the scope for treating women as more usable commodities. It is really in the next century that women began to think of asserting their demand for equal share and equal recognition in policy making. Participation in civil society movements and mobilizations, demands for the right to vote, legal equality or the right to be elected to parliaments and governments were among the important aspects of women's role in politics. Needless to say, even the passage to women's right to vote was not smooth at all let alone right to legal equality and right to be elected, which in many ways still remain dreams to be realized. In Margherita Rendel's words (Whose Human Rights? Trentham Books, 1997), “The ferocity of the opposition to women's suffrage and the lengths to which women had to go to secure the right to vote in Parliamentary elections reflects first of all the extent to which women were conceived of as non-persons.......”

She reminds us of many means women resorted to for the restoration of rights which they believed were their due. These were civil disobedience, hunger strikes, go-slows, lobbying by individuals or groups, publicity stunts such as, to take an example from the British Society, hiding in organ-loft to shout “Votes for Women” at an important political meeting (Strachey, 1928/1978:311). Women of our region have no less significant examples to offer. However, since the focus of my presentation is the interplay of quantity and quality of women's role in politics, I will try to look at the present situation of women in politics, and the role they are able to play in terms of numbers and substantial input in the given situation. Let me make it clear that though the position of women in parliaments and other legislative bodies will be given importance here, their role as voters is no less significant. Participating in large number with a critical mind in electing one's representative is, in my opinion, a vital role women can play and are playing in many countries. Bangladesh particularly has seen how women can outvote the anti-women conservative fundamentalists from taking over power. I will not be surprised to see similar situations in other countries of the world. To look into various average of number of women in parliaments as compiled by the Inter- Parliamentary Union on the basis of information provided by national Parliaments by 31 August 2009. They are: World average: 18.6%, The picture of the South-Asian Average is as follows:

Perhaps at this point it will not be too out of place for this conference to take a brief, but a little more detailed look, into the situation of women in national parliaments and local governments in the SAARC Countries. The way they stand now in Bangladesh, out of a total of 345 seats in the national parliament women have been elected to 65 seats (20 elected through direct election, 45 to reserved seats). The 45 reserved seats are distributed proportionately among the parties sitting in the Parliament. The present Government has announced the plan to increase this number to 100 and hold direct election. In the lowest tier local government, one-third of the seats are reserved for women whereas in the upazila level, the post of the vice-chairman is again reserved for women. Out of 545 seats at the lower house of India the percentage of women elected members is 59.11%. The present speaker of the house is a woman. Under the legislation to be ntroduced by India's newly elected Congress-led coalition government, half the seats in elected village councils and city municipalities will be reserved for women. At present only a third of these seats in village councils are kept exclusively for women. The National Assembly of Pakistan is the lower house. It consists of 342 members, 272 of whom are directly elected. 60 seats are reserved for women in addition to 13 women who are directly elected. The senate of Pakistan is the upper house of parliament. It has 100 members; 17 of these members are women. Nepal has 197 women in the parliament of 594 whereas Maldives has 4 out of a total of 50. Afghanistan has both lower and upper house and the number of women in the lower house is 67 out of 242, and 22 in the upper house out of 102. 2008 has been a historic year for Bhutan with the establishment of a democratically elected parliament, which is bicameral in nature of which the National Assembly is the most powerful having 47 members, and 4 of them are women. It is interesting to note that four of the SAARC countries namely Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and SL have had women heads of governments. Bangladesh enjoys the unique situation where both the position and opposition leaders have been women for about two decades, which as the public perception goes, is not likely to change in the near future. Amartya Sen writes, ”India, along with Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, has had female heads of governments, which the United States or Japan has not yet had (and does not seem very likely to have in the immediate future, if I am any judge). Indeed, in the case of Bangladesh, where both the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition are women, one might begin to wonder whether any man could possibly rise to a leadership position there in the near future.” (Seven Types of Inequality, Human Rights Vision, issue No.22 December 08, 2001). So much for the statistical picture of women's participation in politics. It still needs to be examined how effective women's presence has been in the parliament. To take examples from Bangladesh where the politics is essentially led by women, and especially now, when many of the important ministers as well as parliament leaders also happen to be women, has the general condition of women changed satisfactorily?

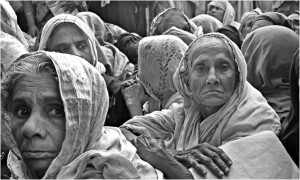

The obvious answer will be 'no'. This 'no' of course will have to be qualified by saying that the women of Bangladesh have become much more conscious of their rights now, especially at the grassroots level. Their participation in political processes is also much more visible. And I would emphatically say that the presence of a significant number of women in politics with two women leaders at the top has worked effectively to enhance the interest and confidence in women as political actors. It still remains to be said that despite all these, women by and large, are still kept out of the decision making process. Most of the women members in the parliament, particularly those who come through indirect election, are apprehensive of taking part in discussions that may hurt the feelings of the party leaders by whose grace they think they have gained their position. During the time of General Ershad, the 30 such women parliament members, because of this very character, were given the name '30 sets of ornaments'. The situation is changing gradually because of the present Government's commitment to women's empowerment. The point I want to make here is that quantity of participation by women is not completely to be ruled out as that definitely gives them a sense of strength and solidarity, but at the same time it is important for them to go through proper processes, for example, through direct election with a defined constituency to get a stronger feeling of solidity of base. We notice a marked difference in the performance between the women members elected through direct election and those selected by nomination. More importantly, the mindset of the fellow political leaders and determination of the leadership to give support to women are extremely vital factors here. Creation of enabling environment is essential which needs to be observed and protected with a firm conviction. This is one of the necessary internal conditions to ensure quality participation of women in politics. Other conditions have to be sought in the women actors' individual and personal capacity. In order to do so an analysis of the ground realities of women's life is necessary. Let us take Bangladesh as a test case. Here we are confronted by the fact that with a very small exceptional percentage of the population, most of the women in Bangladesh live in extreme poverty. No doubt they are the poorest of the poor. They suffer from ill health, inflicted by low level of literacy and rights awareness, without access to adequate information and oppressed by religious, cultural and other kinds of fundamentalisms, which may often lead to violent treatments meted to them. In personal life, they are subject to discriminating laws and continue to be denied the right to seek remedy for family violence. This, goes without saying, affects their general well being so much so that they seldom show enthusiasm in taking the benefit of the Constitutional guarantee of equality and equal opportunities given to them in public life. The other consequence of this is that the political sphere remains under the dominance of few women linked to power through either family, business, finance or social position leaving out many of those who are genuinely politically committed. Therefore, the role these women tend to play is characteristically defined by the motivation for preservation and protection of their family, party, financial or class interests. Another important factor here is that since their power base is not sown in popular support, they suffer from a sense of insecurity, which works as a hindrance to their ability to deliver in the face of serious challenges posed by the societies like that of Bangladesh where democracy has not yet had a chance to work without undemocratic interventions; where divisions, discriminations, inequalities, lack of access to resources on the basis of class, creed, religion, ethnic identity and gender are stark realities. Amartya Sen in his 'Seven Types Of Inequality' aptly names mortality, natality, basic facility, special opportunity, professional ownership and household as areas where women suffer inequalities, therefore, encapsulating the entirety of their lives. Sen goes on to establish, “In some regions in the world, inequality between women and men takes the brutal form of unusually high mortality rates of women and a consequent preponderance of men in the total population.” He talks about 'high tech sexism' where modern techniques are used for sex determination to abort female foetus. There are situations where girls have far less opportunity of schooling than boys. This is true of higher education as well as employment. Demanding equality in property ownership may be considered sacrilegious and hence a punishable offence. Division of labour is very common in many societies and it is common to take it for granted that all household works are the responsibility of women. We are reminded by Sen that it is sometimes presumed that there are more women than men in the world, which may be true of Europe and North America having a female to male ratio of 1.05 (that is 105 women per 100 men). But women do not outnumber men in the world as a whole. In fact, there are only 98 women per 100 men on the globe. This 'shortfall', Sen informs, is most acute in Asia and Africa. For example, the number of females per 100 males in the total population is 97 in Egypt and Iran, 95 in Bangladesh and Turkey, 94 in China, 93 in India and Pakistan. I cite the above information to submit that all these factors have a serious, direct bearing on women's role in politics. This may be illustrated by examples drawn from the Nordic countries, and perhaps some other countries of Europe and America where the situation of women enjoys a comparative advantage in most of the indices mentioned by Sen. One must, however, remember that all socio-economic-political and cultural conditions have to be conducive to generate and sustain a sense of participation as well as ownership in women's minds to enable them to contribute in public life. If the public sphere is reflected as predominantly a male domain and women are treated as intruders, which has been the case historically, neither number nor ability of women will have any use there. To counter that, clear manifestation of the will of the society to ensure congeniality of environment must be evident in the policies and practices of the State, as well as in the municipal laws of the Countries. Rights and dignity of the people must be protected and perpetrators punished to help prevention of violence in due process. Role of the regional and international laws and treaties cannot be undermined either. CEDAW, Beijing Platform for Action, Vienna Declaration must be fully ratified and implemented to provide women with the required support. Regional networks and cooperation have no alternatives in taking the strengthening process forward. All these may sound a little abstract in relation to women's performance as political actors, but the abstract and the practical is interwoven and will strengthen each other. I would also reiterate that gender and general concerns are not mutually exclusive as the socio-economic-political and cultural conditions of a country provide the material environment in which issues of peoples' rights and dignity are decided. Gender is not only about women and democracy is definitely not exclusive of gender. To place the question of women's role in politics and to relate that to the concerns of quantity and quality, it is very important to resolve the relationship between gender and democracy. To experience the full benefit of women's role in politics, it has to be embedded in political stability, democratic practices, good governance, transparency and accountability as these are the most important determinants of human rights, justice and peace - the desired ultimate goal of any political activism where participation with adequate competence is equally important as participation in adequate number. To conclude, I will go back to Sen who so eloquently expresses: ''The expansion of women's capabilities (both quantitative and qualitative) not only enhances women's own freedom and well-being, but also has many other effects on the life of all”. The article is based on a paper the author presented in the Conference on Deepening and Sustaining Democracy in Asia, 11-14 October 2009, Paro.

|

||||||||

© thedailystar.net, 2010. All Rights Reserved |