| |

A cloud of silence in Bangla Town

"They have always been here"- Naeem Mohaiemen journeys to the heart of the Bombay Bangladeshi community

Bombay. Mumbai.

Contested name, conflicted ethnography.

Some friends (Indian leftists) still hold on to the old name, a solitary act of defiance against soft Hindutva.

Bombay. "Maximum city" that leaves me craving, by comparison, the "cleaner" air of Dhaka. It was towards the end of the BJP's horrific tenure (their shock defeat still a pipe dream for Indian progressives), and I was visiting a friend who was in Bombay writing his novel. After days of bemoaning the specter of militant Shiv Sena workers, I decided go exploring the town.

Bombay's Bangla Town was on my radar. I had been hearing about floating Bengali populations. Some called them Bangali, some said Bangladeshi. Invisible, unwanted, and yet essential to the city's smooth functioning. Same as migrants anywhere.

At Raey railway station, I started asking for Bangali-para. A few shop inquiries, and I was sent down a road with hundreds of shanty shacks. The men were all away at work -- women and the jobless sprawled on roadside mats. Also visible were barber shops, where work kept them near home. Tomato, begun, cauliflower, chilis and deformed miniature potatoes in symmetric rows on a blue sheet. A stack of fish fry on a plate: glistening with oil. It looked like it was being prepared for a restaurant, but the lady firmly and sternly informed me she was cooking it for mahalla people. In one corner, a floppy yellow object was being dipped repeatedly into boiling water, it looked like fish but it was chicken skin. On another sheet, a stack of dried, smelly, shutki fish.

Fish everywhere, the trail was getting warmer.

In between cooking areas, girls crouched on the ground, washing themselves with minimal soap and even more minimal disrobing. On more blue sheets, a man was rubbing his head affectionately on a baby's stomach. A crazy jumble of shacks. One-two-three-four, all on top of each other.

When I first approach people, the conversation that breaks off is in Bangla. But when I ask questions, the replies are always in Hindi. No one admits to being Bangali. Dr Choudhary is a Bangali name, the only doctor in the area. But his tiny shop is closed. There are only a few other shops where I can try my search. Trail growing cold again. I step into the last barbershop on the row.

The man sitting in the chair has a thinly shaved pencil moustache and black kohl around his eyes.

"Are you Bangali?"

He answers with a distinct Kolkata accent.

First question everyone always asks: "Apni kotha theke eshechen?"

"I've come from Bangladesh."

Quick as a flash, he asks: "Mmm, passport korthe chacchen bujhi?"

"Bujhlam na," oh, and a beat later, I realise he's asking if I need to get an Indian passport …

"No, no, I'm visiting, I don't want to stay here."

His companion speaks up: "I'm from Assam, where are you from?"

"Dhaka." They both nod their heads. It seems to have meant something.

"But my mother's from Sylhet." Now the second man perks up: "Oh, so you're from my neighboring state."

"Well, we used to be the same state," I joke, trying to lighten the air.

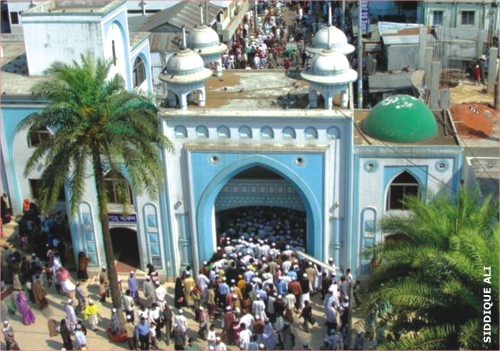

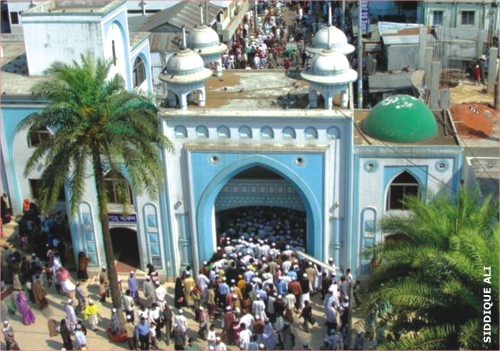

The owner shows up. He has a bushy beard. His Bengali is accented. He says he's from Haora. He starts talking animatedly about Bangladesh: "Yes I go to the Shahjalal mazaar in Sylhet all the time, and also the one in Chittagong."

"You mean the one where you feed turtles bananas?"

"Na bhai, that's Chittagong, in Sylhet you feed them pao fish."

"How do you get there?"

"Oh, I just get a pass and go back and forth. It's no problem, really easy to get through Benapole. Are you taking the bus too?"

"No, I'm flying."

"Oh, apne tho thahole different category. That's not for us. You put yourself in that seat and ... nothing to worry about."

After a few more minutes of conversation, they give me directions. I need to get to Wadala, where there's another big Bangali colony. Okhane onek onek Bangali paben!

But does Bangali mean from West Bengal, or Bangladesh? Or is there no difference in the middle of basti community solidarity ... that part I haven't been able to figure out from these conversations

At Wadala, the environment is very different. The signs here are much more open. A huge slum sprawls on the other side of the train tracks, taking up a few street blocks. Everyone here knows where the Bangali-para is, no puzzled looks. There are blocks of Urdu signs, but every person I ask says, further, just a little further. But as soon as I cross the tracks (stopping to take one furtive photo), walk around the piles of garbage, and step into the area itself, there's a very different reaction.

Although shops carry address boards that say "161 Bangali Para", when I speak to people, no one will admit to being Bengali. Every person says "go over there," sending me somewhere else. I start walking into narrower corridors. There are shacks on every side, tumbling in with barely enough space to squeeze through.

Suddenly I feel very conscious about the large camera I'm carrying with me. I can barely get through some alleys with the camera bag! What prompted me to make myself so conspicuous ...

Finally an Urdu speaking shopkeeper says: "Go up the stairs to the jori factory, they're all Bengali." I climb up slowly with my load and make a bumbling entrance. My bag gets stuck on a pipe, and somebody jubilantly yells from downstairs: "Wo fas giya!" He climbs up to disentangle me and by the time I get upstairs, the jori factory workers are all staring at me. Red-faced, I begin a stumbled, rushed explanation.

"I'm from Bangladesh, I make films, I was here visiting a friend, I'm looking for Bangalis, especially people from Bangladesh …" my voice trails off as the awkwardness of the situation slowly comes home.

In a city where the Shiv Sena plays politics with the juju of "illegal Bangladeshi" migrants. In a volatile situation where "push back" has entered the sub-continental vernacular. Where election season means giving instructions to pakrao the "illegals." Where Bangladeshi is also the BJP's coded way of saying "Muslim." Walking into a slum where the BJP-era police were rounding up and deporting suspected Bangladeshis, who will admit to being Bangladeshi to me?

"Who are you?" one of them asks, he can't have been more than sixteen. I start my explanation again and halfway through, he interrupts and says in Hindi: "Speak to us in Hindi, we don't understand Bangla!"

"But you just spoke to me in Bangla"

"No, we don't understand Bangla, we speak only Hindi, we don't know what you're looking for."

The music was turned down. One of them turns it back up. Hindi. Filmi. Loud.

I keep trying for a few minutes. The pathos of the situation seeps in and I give up. I start climbing back down, careful about my bag this time.

"What happened, bhaisaab?" asks the Urdu-speaker downstairs.

I explain, embarrassed, like a jilted lover.

"No, no, they're lying, they're all from Kolkata."

"Hey," he yells up, "Thum jhut kiu bola …why did you lie? "

Then turning to me: "Listen, no one wants to admit being Bangali, because the police are always looking for Bangladeshis. It means anyone who's Bangali and Muslim is a suspect. Then they threaten to deport you, you bribe them 2,000 rupees, and they let you go. Sometimes they put them in the van for show and let them off a mile from here. It's all about money."

Someone else: "You need to tell them you are a journalist, you will print their photo."

I hesitate: "I don't think that will reassure them." (I'm not a journalist anyway.)

Another man chimes in: "We're not afraid, take our photo."

"But you're not Bangali."

He breaks into a smile. "Yes, that's why I don't care if you take my photo. Listen go to that store. They are older, they are not as afraid as those kids."

I climb up another flight of stairs. This time, puzzled looks again, but not as much hostility. They listen, and continue their jori weaving work. After the explanation, the man in front starts speaking. Very precise, with a strong Kolkata accent.

"Listen, no one will talk to you, everyone is scared. We're not scared, that's why no one has ever given us trouble."

Another craftsman speaks up: "But even if they do, so what. Listen bhai, those who are scared are usually the ones they catch."

They're speaking in turns, filling in each other's sentences with comfort: "But it's all for bribery. They want a bribe, otherwise they'll send you over the border. They even cut off your shirt label, so no proof of where you came from."

"But when they get to the border, Bangladesh doesn't want them either. Why should they, ey apod abar kottheke elo? And another thing, they separate families. Men are put in one camp, women in another, children in a third one. If you really want to push people out, this is not the way you do it."

"So … do people here think I'm with police?" I ask at last.

"No, no -- no one thinks you're CID. But your clothes, your hair, your shoes, and the samal you're carrying makes you look different, so people are nervous. What does he want, they are asking. You arrived suddenly, no one knows you. This is not the proper way to come to our area. Come with introduction."

Another man joins in: "But you should be careful, coming here where you do not know anyone, with all that samal, anything could happen. Even in the daytime. You shouldn't have come here with all this stuff."

"But I have a passport. I'm carrying it with me!"

"So what, if police rip up your passport, what will you do? You'll speak English, they'll pretend not to understand. You'll speak Hindi, they'll pretend not to understand. It takes nothing to put you in jail."

"But I'll tell you what no one will admit. There are maybe 700,000 people here. At least half are from Bangladesh. Maybe they came now, maybe they came before partition, no one knows -- how could they? They have always been here."

They start to warm up, and get a little angrier too. "But now no one wants to admit it because you will get thrown out. It's completely unfair, just politics and money. Some of these people have been here for generations, suddenly at night they are getting the knock."

This goes on for a while. Hostility to the police, to the politicians, to the BJP. All seeping out, bit by bit.

"How long have you been in the jori business?" I finally ask.

"We Muslims have been in it for a long time, you could say this is our khandani. But now Hindus have also come in, so prices have gone down. You can barely eat on this. That's why all our families are back in Kolkata."

The first man looks up at me, staring for a moment, before asking his question.

"Are you Muslim?"

"Yes. And you ...?"

He just points to the Arabic script on the wall.

"Yes, all the people in the jori business in this neighborhood are Muslim. So ... you can celebrate Eid with us."

A new person enters. He's younger and seems to be the manager. He looks over at me, suspicious and watchful. The mood is broken, conversation withers away. Everyone goes back to work. A bottle of Pepsi arrives for me.

I ask permission and take a few pictures. We think of exchanging information. They have no address to give me.

"What about this factory?"

"No point giving you this address, tomorrow you may come back and I may not be here. Maybe next week, the whole slum will be gone. It's happened before."

"But take my address, and if you come to Bangladesh, please visit."

They nod.

But we all know, they're not coming to Bangladesh.

It takes a long time to say goodbye. I stay another hour. They give me Pepsi again. The conversation is light, scattered over the sound of work. But they seem mystified by my desire to leave.

"Why do you want to leave quickly?"

I explain that I am in Bombay for a few days, want to spend some time with my friend. They nod but don't really pay too much attention.

Finally, it's really time to leave. As I get up, he stops me, "Ok, one very important question for you."

"Yes, go ahead ..."

"Do you really think they got Saddam?"

I'm a bit stupefied. This? This is the big question?

The others join in enthusiastically, this is clearly the burning topic on their mind.

"We all think that's a copy. Otherwise why do they have to check his teeth?"

"Saddam is not a hero, a woman! How did he get caught? Why didn't he kill himself, that's what I would have done."

We argue about Saddam for a bit. Real? Copy?

Finally, I stop it. "Listen this conversation will never end. I really have to go. Getting late. Long way to my friend's house. We'll talk about it next time."

"Yes," he replies, "Next time."

Naeem Mohaiemen is a Forum contributor. |