Inside

|

Epaar Opaar Udayan Chattopadhyay reflects on the border divide

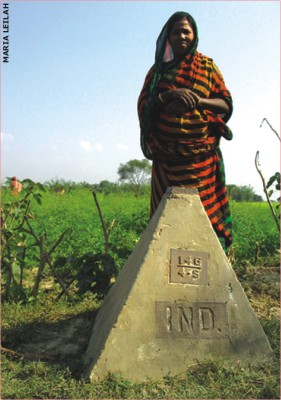

We can see the border very clearly from the temple roof. A disciplined line (by Bengali standards) waits on both sides, with papers in hand, eager to cross to the other side. Indian and Bangladeshi officers -- distinguishable by their different uniforms -- are busy processing documents, opening bags, conducting body searches, and then waving people through to their counterparts on the other side. Within clear visibility, though a distance away, is another portion of this border; here, there is utter chaos on both sides -- crowds of people, trucks, cows, goats, bullock-carts -- and the movement is more fluid and erratic; officers from either the Indian or Bangladeshi side are nowhere to be seen. "That line isn't for people like us," one of the temple staff assures me as he notices my fascination. "There they just come and go as they please, they don't need papers like we do." As we go around the temple, the purohit explains that during the big festivals the bulk of the visitors are, in fact, from Bangladesh. During Durga Puja, they construct huge tents outside the premises; Indian visitors are primarily local or day-trippers, but Bangladeshis usually stop overnight on their way to Calcutta and beyond. "Are they Hindus only?" I ask. They explain that it is much easier to cross during religious festivals, when border guards can be more readily convinced that the travelers are undertaking quick family visits. At the market right outside the temple I notice that many of the publications -- mainly religious books -- are from Dhaka and Khulna rather than from Calcutta. "They are cheaper than the ones from Calcutta," explains the hawker as I fumble through the pages, more interested in how the books got to India than in the contents. A rival hawker, who perhaps does not have access to the cheaper merchandise, asserts harshly: "Those Bangladeshi books are terrible. They will fall apart within a couple of days. My books are more expensive but they are Indian and better." I chuckle with my family at what seems to be harmless banter -- until the seller of Calcutta books rebukes his neighbour: "You Bangals, you are ruining our country. Why don't you just go back to where you came from?" And he's not joking. This exchange sends shivers down my spine. Having grown up in London as an Indian immigrant, battling bullies in the school playground, and having lived in New York through the post 9/11 hysteria, hearing "go back to where you came from" -- in any language, in any geography -- momentarily paralyses me. I do not know whether he is one of the Bangals whose family, like those of an estimated 25% of West Bengal's population (20 million people), crossed over from o paar in the decade after 1947. Or is he part of a later phenomenon -- the post-1971 Bangladeshi migrant, estimated by many in India to be between 5 and 20 million. And if the latter, is he an economic migrant (both Hindu and Muslim) or a refugee (invariably Hindu)? I have spent hours debating with my Bangladeshi friends the very existence of the phenomenon of Bangladeshi migration to India, and the nuances behind these categories, but seeing the hurt on the "Bangladeshi" man's face, I don't really care for labels at this point. This is obviously not the first time he has heard this kind of talk. It is a reminder of the rising passions across India on the issue of Bangladeshi migrants. When in Dhaka a few months later, I find myself thinking about the same issues. A rickshaw puller identifies my accent and starts grilling me: "Are you from Calcutta? What are you doing in Dhaka? Are you Muslim?" I have come to realise that, when not coming from uniformed officers, such questions usually reflect the endearing Bengali characteristic of curiosity rather than hostility, so I engage with him. He proceeds to tell me: "My uncle lives in Krishnanagar. We are originally from o paar. My brother now works there." He asks if I have been there; I have not, but he has, many times. "I go every year for Eid. This year I will take my children for the first time." I ask him if it is difficult to get a visa. He laughs. "What visa?! People like you need visas, we just go whenever we feel like it, no-one can stop us." He caustically points out, "Your border guards demand more money than ours to cross. You Indians are thieves." The problem when discussing migration from Bangladesh to India starts with the disconnect between the two countries on the very existence of the issue, let alone the scale. Indian officials have gone on record quoting figures as high as 20 million Bangladeshi immigrants. Their Bangladeshi counterparts stick to the official position dating from General Zia's era -- that there is not a single Bangladeshi migrant in India. The respective national media usually echo the official positions. In both countries, the subject of migration eventually touches some extremely raw nerves that hit at the heart of the national psyche. The modern state of India was founded on the principle of a pluralistic secular democracy defined by a vision rather than demographics; the land that Nazrul described as Udar Bharat, opening its arms to all mankind; the country comprising, as Tagore celebrated in his Bharat Tirtha, of a sea of humanity from all over the world that, once in India, would never leave. However, even among those who swear by this vision for India are those who are increasingly vocal in their discomfort with the growing Muslim population in eastern India, which many believe is driven by immigration from Bangladesh. They point to statistics from the census: West Bengal's Muslim population has risen to 25% in 2001 from 21% in 1971; corresponding figures for Assam are 31% in 2001 and 25% in 1971.

There is an eerie hypocrisy at work here; if such idealistic visionaries are silent about other undocumented migrants in India -- including an estimated 10 million from Nepal, as well as those from Tibet and Sri Lanka -- why is it that the presence of Bangladeshi Muslims in particular raises such cries of protest? And why are Hindu Bangladeshis universally seen as refugees, while Muslims are seen only as illegal migrants and a potential security risk. Most shockingly, what message does this framework -- that a disproportionate rise in the Muslim population is bad -- send to native Muslim populations in West Bengal and Assam, not to mention Muslims from other regions of the country?In Bangladesh, there is a similar discomfort when confronting the issue of migration to India. The existence of a Bangladeshi diaspora, both legal and "illegal," is acknowledged and even celebrated in most cases; past Bangladeshi prime ministers have publicly voiced support for legalising undocumented migrants in countries such as US, Malaysia and Brunei, for instance, taking up the matter with their counterparts at an official level. However, given both the tumultuous history of East Bengal post-1947, and the current relationship dynamics between India and Bangladesh at a national level, to accept that Bangladeshis would willingly choose to migrate to "Big Brother" India for a better life is perhaps difficult for many to accept. India, of course, has its own diaspora of economic migrants (with twice as many Indians having "illegal" status in the US compared to Bangladeshis, for instance) as well as a population of 400 million below the poverty line (i.e., more than double the entire population of Bangladesh itself), but such metrics, which put India "in its place," do not seem to provide comfort to those seemingly worried about bruised national pride in acknowledging the situation. Particularly when prominent Indian politicians make statements such as: "Migration is a means for Bangladesh to outsource its poverty and squalor."

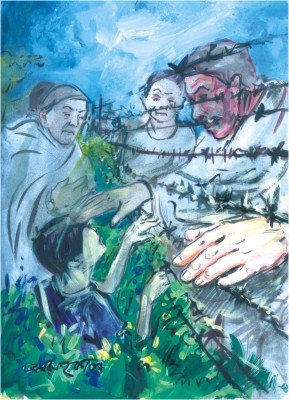

Bangladeshis should be reassured, however, that the harassment of supposed Bangladeshi migrants in India has not gone unchallenged. There is a vocal lobby that systematically protests the brazen declarations calling for mass deportation, challenging both the identification of alleged Bangladeshis, and the human rights behind the means and methods. Mamata Banerjee, leader of the Trinamool Congress, famously declared in the Indian Parliament, following the most aggressive drive by the Maharashtra government to identify and deport illegal Bangladeshi immigrants in 1998: "Even if somebody is a Bangladeshi, he should not be treated like cats and dogs, as we have traditional ties, ethnic and common culture with Bangladesh … So, a message should go to the people that nobody should be harassed like this and the people should not be tortured like this." Indians must confront several demons in their national psyche when considering the issue of Bangladeshi migration. The unpleasant truth is that many of those who have come to India have, in effect, already been legalised; by the Indian border guards who took payment from either the migrants themselves or the dalals responsible for bringing them over. Not to mention by the Indian politicians of all political parties who have granted ration cards to migrants in return for their becoming loyal voters. Many of these migrants have been in the country for several decades, and have had children born in India. Doesn't questioning their status and seeking their deportation violate a fundamental principle of human rights -- that rights once granted cannot be withdrawn? And just as the US has a steady stream of undocumented migration from its southern border with poorer Mexico, as long as trade imbalances and economic disparity exist with Bangladesh, no matter what laws are in place, migration is likely to continue. As India increasingly seeks to present itself as an emerging superpower, it must pay closer attention to the message that its means and methods in dealing with this situation sends to the global community.As far as Bangladesh is concerned, there should be recognition that refusing to discuss or acknowledge the situation is a growing irritant in bilateral relations, ranking alongside trade, the environment, and terrorism. There are other sensitive issues for Bangladesh to consider as well; the continued existence and implementation of the Enemy/Vested Property Act is itself responsible, perhaps, for a significant portion of the migration of Hindu Bangladeshis to India since 1971. Flashpoints, like the riots of 1992 or the post-election violence of 2001, trigger noticeable spikes in the flow of Hindus crossing over into India, and this is an area where Bangladesh must confront demons of its own. Official denial of migration to India in general also raises the dangers faced by Bangladeshis in India and increases the likelihood of their being abused.

Much of the domestic labour in Calcutta is now Bangladeshi, and consists primarily of women and children. Living in constant fear of detection and deportation they are liable to be underpaid, and have little recourse to complain if working conditions are unfair or even inhuman. The implications are greater for the hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshi men who work in India's factories, and increasingly on construction sites throughout cities such as Calcutta, Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore, where they are invariably the workers with least physical protection and no likely compensation in the event of accidents. With Bangladesh in denial mode, India increasingly hostile, and employers with no incentive to seek anything other than the highest profit margins, this largely poor population is a pawn in larger power games. Udayan Chattopadhyay is a Forum contributor. |

A

A

Some Bangladeshis accept that there may be migration, but are concerned both by the scale suggested by India, and by the reaction. There may be a legitimate fear that the moment Bangladesh accepts the existence of illegal migration to India, there would be legal sanction for India to take draconian measures in response. The phenomenon of "push back" (deporting identified illegal immigrants back to Bangladesh -- known as "push in" in Bangladesh) is one example, and such practices in larger numbers than the occasional occurrences at present would certainly be horrific from a humanitarian point of view, even with legal sanction.

Some Bangladeshis accept that there may be migration, but are concerned both by the scale suggested by India, and by the reaction. There may be a legitimate fear that the moment Bangladesh accepts the existence of illegal migration to India, there would be legal sanction for India to take draconian measures in response. The phenomenon of "push back" (deporting identified illegal immigrants back to Bangladesh -- known as "push in" in Bangladesh) is one example, and such practices in larger numbers than the occasional occurrences at present would certainly be horrific from a humanitarian point of view, even with legal sanction.