Inside

|

Through Big Brother's eyes

In short, the rising incidence of militant activities of extreme Islamist parties, the suppression of the rights of minorities in the name of Islam, the infiltration of exogenous religious entities, the setting up of training camps on the outskirts of the country, the enlistment of Bangladeshi men in the movements in Afghanistan, Iraq, and most recently, Lebanon, have all drawn attention to the potential dangers posed by this small country in a world that is defined by the "war on terror." Once described as a secular, moderate Muslim country (a description that is proudly accepted by Bangladeshis in general), Bangladesh is fast becoming a zone of "special interest" in the US State Department and in US foreign policy-making. It is time for the rediscovery of Bangladesh, this time as a Muslim country with a secular political platform. In recent conferences on Islam's compatibility with democracy, Bangladesh, along with Turkey, was held as a shining example of a successful marriage between secularism and religion. At the same time, the avid interest in the political developments in the country, and its role as a strategic partner in the "war to end all wars," implies that there is growing concern about the general pattern that is emerging in the country. All of a sudden, Bangladesh presents itself as both, a threat and an ally, in this new global paradigm. The shift from being a small South Asian nation of negligible importance to the realpolitik interests of the United States to one that has emerged as a partner in strategic, political and economic alliances has not happened overnight. The developments in Bangladesh, and the concerns surrounding its militant activities, have been in the consciousness of policy-makers for quite a while. Perhaps, the most prominent indicator evidencing these concerns comes in terms of the development of the Failed State Index, a newly developed comprehensive indicator that is designed to communicate the dangers of countries failing to constitute effective and operational state mechanisms. The design of the Failed State Index was not developed in a vacuum. In July 2004, the US State Department opened the office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization (S/CRS). Its official mandate is to "help stabilise and reconstruct societies in transition from conflict or civil strife, so they reach a sustainable path toward peace, democracy and market economy." The idea of a standing nation-building office has garnered significant support in the Bush administration, along with many in the academic community and among foreign policy analysts, and key players in the Congress. One of the main points that favour such a rationale is the ingrained belief that failed states are a threat to US national security. According to Senator Richard Lugar (R-In) of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: "International crises are inevitable and, in most cases, US security interests will be threatened by sustained instability." The notion that failed states are indeed direct threats to the United States has grown stronger since the September 11 attacks, and with the release of the United States National Security Strategy in 2002 and the National Intelligence Strategy document released in 2005. The latter states: "The lack of freedom in one state endangers the peace and freedom of others, and failed states are a refuge and breeding ground for terrorism." The bandwagon for the new policies toward actively promoting democracy-building in "failed and failing states" has never been so full. In 2005, Foreign Policy magazine published the first comprehensive Failed State Index, devised by the US Fund for Peace. With categories such as mounting demographic pressures, criminalisation or delegitimisation of the state, progressive deterioration of public services, widespread violation of human rights, uneven economic development, and sharp or severe economic decline, the index intended to capture the full breadth of the political and economic crises that overcome countries and contribute to their instability; in the context of 9/11, they are also the breeding grounds for "terrorism," and, hence, the nesting-grounds for anti-US threats.

How are failed states defined? In layman's terms, they are generally categorised by what they do not, or cannot, do. Failing and failed states do not control their territory or their borders, creating the scope for groups to move in and out without hindrance. Such states also do not control many areas, which can be under control of rebels and warlords, and do not provide basic services (health, nutrition, infrastructure, public services). Finally, they cannot fulfill international treaty obligations, and agreements of international concern. The most extreme examples are, of course, places like Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Haiti and, increasingly, Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2005 and 2006, the two years in which the Failed State Index came out with its full list, Bangladesh occupied the 17th and 19th positions, respectively. The countries that were higher than Bangladesh were mostly those engaged in full blown conflicts, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, the Congo, and Somalia, and those that had high levels of political tension, such as Sierra Leone, Colombia, and North Korea. Granted the economic performance in Bangladesh, and the existence of a legitimate centralised administration, it was weak political performance, corruption, political tension, growing marginalisation of minority groups, and the rise of militant groups that contributed to its position in the ranking system. The question then is, how far is the Failed State Index relevant to understanding the interest that Bangladesh supposedly arouses in the United States? There are many who will contend that failed or failing states are potentially dangerous for US national security. Yet, with the trans-national nature of militant activities, as a backlash of the Afghan and Iraq wars, the grounds have been clearly established for considering the militant face of Islam as being a key reason for a closer look at Bangladesh politics. And Bangladesh has delivered. Because of allegations of jihad training camps, national bombing campaigns, threats to embassies and international NGOs, greater radicalisation of madrassas -- the stronghold of political Islam -- Bangladesh has made itself increasingly prominent. In the end, the existence and expansion of these networks contribute greatly to an understanding of Bangladesh as a country that manifests some of the most critical indicators of state failure.

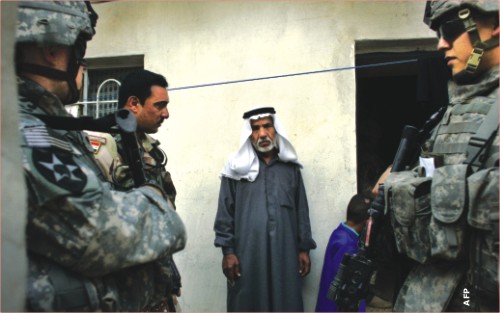

The response of the United States to countries labeled as failing states is many-fold. The most prominent, of course, is the enforced package of democracy under the gun. It is believed that the imposition of democratic institutions will overnight create an entrenched democratic culture; an enforcement of electoral democracy will establish viable democratic norms. While the results of these experiments are unfolding in Iraq and Afghanistan, other efforts are also underway, the newest of which is madrassa reforms in Pakistan. It is only a matter of time before this package will also be offered to Bangladesh. Then, too, is the strategic national decision for co-optation and rejection. While Turkey has historically marginalised political Islam, Afghanistan has begun making overt efforts to integrate the Taliban into the political mainstream. In both these cases, and cases in between, the challenge is to uphold the legitimacy of some political Islamic parties while ensuring that more virulent forms do not sabotage their mandates. In each of these cases, the cost of the choices and the mistakes made will be borne by the constituents. In the case of Bangladesh, it is well within speculation that the rise of extreme religious movements will be monitored closely, and evaluated within the new paradigm of state failure or success. While the caretaker government attempts to clear the decks, and the elected party in 2008 responds to the economic and political challenges in the country under the watchful eyes of Big Brother, the task of "managing" political Islam will perhaps be the most daunting, and most critically observed of all. Tazreena Sajjad is a contributor to Drishtipat Writers' Collective. |

B

B