Inside

|

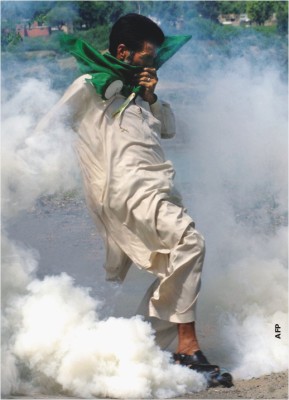

Writing Pakistan There is more to the renaissance in Anglophone literature in Pakistan than a post-9/11 bump, argues Kamila Shamsie There is much for Pakistanis to be depressed about these days, so soon in the aftermath of the October 18 bomb blasts in Karachi -- which in turn, followed on from the so-called National Reconciliation Ordinance which paved the way for Benazir's return.

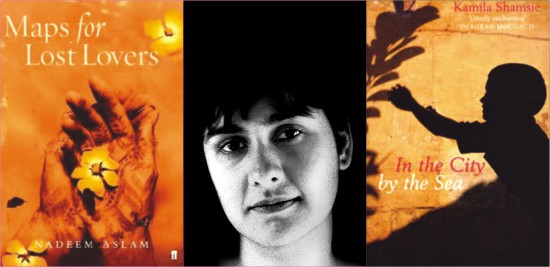

I had already decided, pre-October 18, what my column this month would centre on: my friend and compatriot, Mohsin Hamid's inclusion on the Booker shortlist. For a couple of days after the bombing, though, it seemed indecent to talk of books when so many had died on the streets of my hometown. And yet, here I am, about to talk of books -- quite simply because there is a way in which conversations about writers from Pakistan do tend to get caught up in conversations about the so-called War on Terror and its various tentacles, so this time of violence seems suited, in a horrible way, to take on the matter. Let me start with the assertion that it's been a particularly good year for Pakistani or Pakistan-origin fiction writers (I'm going to conflate the two into one for this article). Mohsin's presence on the shortlist -- which makes him the youngest ever shortlisted author -- is both icing on the cake and cherry on top. But in the last year there have been three highly-talked about book-deals in the UK involving Pakistanis: Mohommad Hanif's "A Case of Exploding Mangoes" which centres around the assassination of Zia-ul-Haq; Nadeem Aslam's "The Wasted Vigil" which is set in Afghanistan, spanning a time period from the Soviet invasion to the US War on Terror; and Daniyal Mueenuddin's short story collection "In Other Rooms, Other Wonders" which tells inter-linking stories of class and power. Add to this the writers who have had book recently published, or in the pipeline -- Uzma Aslam Khan, Moni Mohsin, Aamer Hussein, myself -- and you have a more substantial body of work than has ever appeared before from Pakistan in the form of Anglophone fiction. And though I may be biased here, I also think it's very, very good. But there is a dispiriting side to things as well. Whenever I try to talk to people about all that is exciting in the world of Anglophone Pakistani fiction the term "9/11" always works its way into the conversation. As in: "Oh yes, post-9/11 everyone wants to read about Pakistan."

Recently, I was talking to two writers of Pakistani origin when another writer (with no Pakistani or Muslim connections) came up to us and said: "The moment I saw the towers fall I thought, oh hell, now those Asian writers have it all stitched up. No one's going to want to hear from the rest of us for a long time now." The three of us who were "Asian writers" were -- and for writers this is rare -- entirely without words. On a similar note, Mohsin Hamid was recently asked in an interviewer how he felt about the fact that in some way he owes his great success to Osama Bin Laden. Funnily enough, I don't suppose Don DeLillo, John Updike, Martin Amis or any other of the writers who have written work connected to 9/11 get asked this sort of thing a great deal. Haven't writers always engaged with the significant political events of their time? Why must conversation about Pakistan writers carry this undertone of derision, as though to say our worth is entirely contingent on the fallout of history? This is not to deny that the world outside South Asia is far more interested in Pakistan now than it was seven years ago, and for the worst reasons. But if one of the ways in which this interest gets expressed is a greater willingness to engage with the cultural production of the nation, surely this is a silver lining. Perhaps there are Pakistani writers out there attempting to "corner the market" by writing the kinds of stories they think the world wants to hear -- but these writers don't include Nadeem Aslam and Mohsin Hamid whose books may seem incredibly timely now, but both of whom had spoken to me about starting to work on these particular projects pre-9/11. That should say something about why people need to pay more attention to writers. Their work doesn't merely respond to what happened yesterday, but also considers what might come tomorrow. 9/11 forced a re-shaping of both The Reluctant Fundamentalist and The Wasted Vigil, but the central storylines already existed. And from what I can tell, Hanif and Mueeniddin's books are not explicitly "9/11 books" (already that's becoming a genre) -- on the contrary they appear to be a valuable addition to the library of books which rounds out views of Pakistan rather than confining the country's entire history and society to the realm of "what led up to and onward from 9/11." As Bangladeshis know better than anyone else, there is more to Pakistan than the tribal belt and the ISI. Kamila Shamsie is an eminent Pakistani author and columnist.

|

The NRO left many of us from Pakistan feeling that there was nothing but cynicism left in us regarding political events in Pakistan (more than one commentator pointed out that the problem with claims that the NRO modelled itself on South Africa's "Truth and Reconciliation Commission" was that the NRO handily left out the "truth" part.) But October 18 left us almost nostalgic for cynicism, which was completely trumped by horror. And a tremendous sorrow.

The NRO left many of us from Pakistan feeling that there was nothing but cynicism left in us regarding political events in Pakistan (more than one commentator pointed out that the problem with claims that the NRO modelled itself on South Africa's "Truth and Reconciliation Commission" was that the NRO handily left out the "truth" part.) But October 18 left us almost nostalgic for cynicism, which was completely trumped by horror. And a tremendous sorrow.