Inside

|

Photo Feature

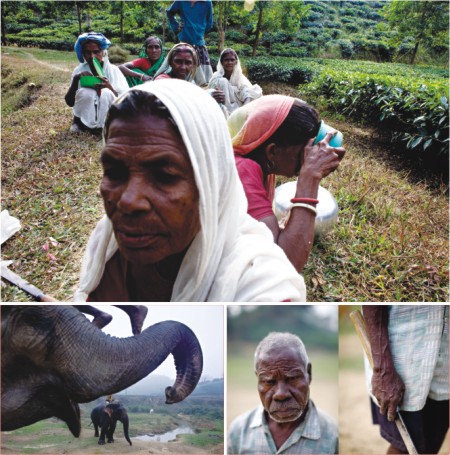

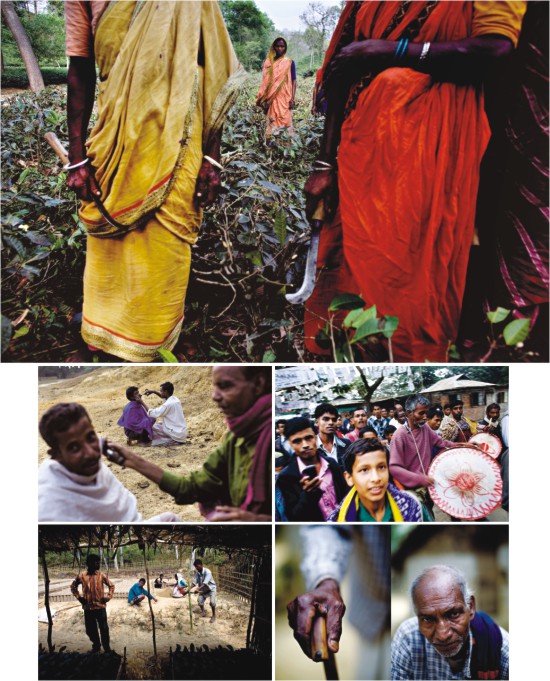

A photofeature by Thomas T Kleiven/OUC The hot sun is shining over the spread of tea plantations in Sylhet. As far as the eye can see there are only the green leaves of the tea trees. Beads of sweat trickle down the foreheads of Biroja and Badoli when they swing their shears repetitively over the plants. Outside his little mud house in a village some distance further in the garden sits 75-year-old Gogendra on a little chair. He wants to go back to India, he says, but he also wants to make some money to provide for his children. What he makes now is hardly enough to feed them. On the ground behind him sit his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Everybody who lives and works at the plantation is dreaming about going back to India. But for most people that thought remains just a dream. In 1854 the British put up the first tea garden in the northern part of the river delta north of the Bay of Bengal. Instead of teaching the local people how to do the demanding work on the tea gardens the British brought with them Hindus from India. The labourers wrote contracts that would keep both them and their children in the garden. They did not go home as they had planned to do. In Khadim and Burjan tea estate outside of Sylhet the forest tea plants were planted in 1889. Since then several generations of Hindus have worked with the production of tea, which is exported all over the world. The feudal system that the British set up in the 1800s is still very visible. The authorities are supposed to provide the labourers with free housing, medical services and education for their children. But only a third of the children are attending school. They end up working in the garden instead. The salary of 30 takas per day is not enough to feed a whole family. Without education the children have no other possibilities than to work at the tea plantation for the rest of their lives. From Pathshala-Oslo University College reportage project 2009

|