Inside

|

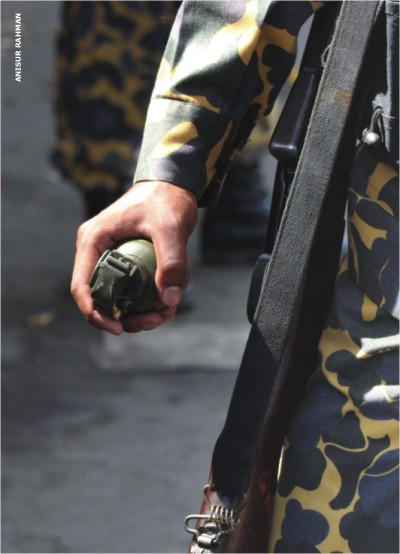

Who Will Speak for the BDR? Hana Shams Ahmed highlights legitimate issues that disappeared in the massacre's aftermath "The subaltern uprising story has paled away as threats to the nation's territorial sovereignty have become clearer". -- Rahnuma Ahmed, New Internationalist (UK), March 17 Six weeks into the bloody carnage at Pilkhana, black banners are still hanging outside the BDR grounds. This is the site where the bodies of 74 people, including 57 military officers, were recovered from mass graves-- a political and emotional shock from which the nation is yet to Two of the most noted army officer victims were director general of BDR Maj Gen Shakil Ahmed and Col Gulzar Uddin Ahmed, the founding director of the intelligence wing of RAB (Rapid Action Battalion) who led the operation to arrest JMB militant leader Shaikh Abdur Rahman. Public perception first focused on the initial reports on day one about a rebellion centred over pay, rations, corruption, and lack of opportunities. But by day two, public outcry broke out as reports about savage killings started coming out. The "Proletariat Revolution" theory had initially been facilitated by interviews with rebels in orange and red masks, expressing their pent-up resentment over low salaries and alleged corruption in the BDR upper-tier. From the first moments of the initial shooting around 9 in the morning, citizens were scrambling to make sense of events that rolled out live, a significant difference from past conflicts. Every action was under the media camera, as well as by the many personal digital and cell phone cameras of citizen journalists. Unlike past conflicts, it seemed impossible to have any distance to understand or analyse events in the breaking hours, as one breaking news item was replaced by another. On the other side of this complex event, the actual grievances of BDR soldiers, especially those who were not involved in the mutiny, are also based on some elements of reality. However, whoever are the architects behind this horrific killing at Pilkhana, they cannot have had the welfare of the BDR personnel in mind. The scale and nature of the killings has in fact created a strong backlash against all BDR jawans (not just the core mutineers), and there is strong possibility that BDR itself will end up dissolved and restructured. Although rational discussion of BDR demands has been made impossible by the killings, the government still should look at the legitimate demands, while making it clear that such bloodshed can never be an acceptable form of demand or negotiation. What exactly were the grievances that may have fueled an environment where conspirators could foment bloodshed? According to an anonymous BDR officer (speaking to Julfikar Ali Manik of The Daily Star), they only get Tk 5,000 as salary, which is not enough to cover monthly expenses. BDR jawans have been demanding their full food ration for some time, but had been getting only 60 percent.1 The anonymous interviewee also claimed that the residential facilities for the lower-level personnel are very poor, while those at the officer level enjoy good facilities. Just before February 25, a letter was allegedly sent to the prime minister with a list of 54 demands to improve the conditions of this paramilitary force. Among the demands were: the BDR still don't receive 100 percent of the food rations, the BDR are never sent on foreign missions although they have always been promised, they never received their rightful share in Operation "dal-bhaat," the BDR never got the daily allowances they were promised involved with their duties during the national and upazila elections, although the BDR are always in the line of direct fire at the border they are not getting defence benefits, vehicles bought under the name of BDR are being used by the army, children of BDR personnel have to study in schools outside the BDR compound while children of army officers and their families study in the BDR schools, etc.2 Army officers also enjoy such facilities as residential plots in Defense Officers Housing Society (DOHS), as well as benefits from entities owned by Army Welfare Trust. These grievances were expressed, signed, and reportedly sent to the prime minister just before the day of the killings. Whether the PM's office had actually had a chance to review this list is not clear. In addition, there are reports that two MPs were also contacted about the grievances. Since these grievances had been solidified into petition form, it can be safely presumed that most of the jawans of BDR were duped into believing that this is what the mutiny was all about, about pressing home their demands. But, as is clear, the massacres in fact derailed any likelihood of the grievances getting any fair hearing in this emotionally turbulent aftermath. This is not the first expression of discontent in the BDR. During the first BNP government, the BDR soldiers staged small mutinies in Dhaka, Chittagong, Feni, Jessore, Khulna, and Naogaon, expressing similar grievances.3

The Ansar Police Force also staged a revolt during the BNP government, which was, ironically, suppressed by this same BDR.4 Farhad Mazhar wrote about the Ansar rebellion that took place on December 1, 1994 during Khaleda Zia's rule. The most marginalised and economically deprived of the government para-military forces were working hard day and night to beef up Bangladesh's security. In return they were not getting what they were promised as basic needs. In the end they took up arms to press for their demands. The government put down this revolt swiftly, and almost 30 Ansars were killed in the process. Farhad Mazhar ended up going to jail for his article, which expressed some understanding and sympathy for the Ansar's demands. Although it will not be a priority for many, it is important to separate the murder investigations from the legitimate grievances of the BDR. The killings were masterminded by a certain group of people, who had neither the BDR's nor the country's welfare in mind. And whoever was behind the carnage is so far getting their way, because the country is facing destabilisation in the aftermath. The genuine BDR grievances have now taken the furthest back seat and public opinion oscillates between various conspiracy theories -- it's the work of the Islamic militants, it's work done by the government itself to make the opposition look bad, it's the opposition's effort to destabilise the government, it was done by the army itself to bring the country under military rule, it's ISI, it's RAW, the list goes on. The death of six key witnesses while in custody, and the evidence of torture marks on at least one of the dead witnesses, makes one wonder whether evidence is being destroyed. The government spokespersons making public every new lead into the investigation will pacify a public hungry for fresh details, but will endanger the investigation. Any BDR personnel who killed army officers should be punished. No grievance, however strong, justifies such acts of mass murder. The investigations may uncover the killers, but it is not clear whether they will reveal the actual masterminds, who, according to newspaper reports, were feeding fuel into the angry psyche of the BDR soldiers. Meanwhile the media circus around the investigation is making it less likely that we will end up with a transparent, balanced process. In fact what method is actually legitimate to express dissent or grievance in this country? When the garment workers ask for a pay rise and better working conditions, they are labelled as "disrupting peace." When slums are ravaged to the ground, the slum-dwellers at the very end of the food chain cannot protest. There is no peaceful platform for many citizens to speak out against these gross violations of their rights. And it is precisely in this context that desperate individuals resort to violence to push home their demands. The lesson Bangladesh has taught them is that only violent demands and action, accompanied by collateral damage to cars, building and property, gets the government's attention. It is likely in this national context that at least one section of the BDR jawans were upset enough to consider a mutiny as a legitimate and productive path, and then groups with agendas of destabilisation stepped into that situation, fanned the flames and carried out the murders. The government has a huge task ahead of it to sift through the wreckage and find the real motive and culprits behind the killings. In the process, it must ensure that no more lives are lost in custody and the nine deaths that took place so far are accounted for. But at the same time, the grievances of the BDR personnel should also be explored in detail and with a neutral eye. If some of the concerns are genuine, they should be resolved, so that frustration, which can be exploited, does not arise again. Here there is a difficult balancing act. The government will wish to appear tough and decisive.

One section of the government might well advise that addressing any of the grievances will only make for incentives for future acts of violence as a form of pressing home demands. This fear may even push the government to suppress any legitimate demands so as not to be seen as "soft." But left unaddressed, issues of disparity of wages, rights, and opportunities, could fester and create another future scenario, which can be exploited by shadowy players wishing to destabilise the country again. Hana Shams Ahmed is Assistant Editor, Forum. 1. Julfikar Ali Manik, "How it began," The Daily Star, February 26, 2009. |

recover.

recover.  Those mutinies did not end in bloodshed, nor was there much media coverage, and in the end personnel were assured of measures to address their issues. Those measures were never properly taken, and grievances continued to fester.

Those mutinies did not end in bloodshed, nor was there much media coverage, and in the end personnel were assured of measures to address their issues. Those measures were never properly taken, and grievances continued to fester.