Inside

|

Untangling the Web SHAHEDUL ANAM KHAN offer's a critical overview of the BDR saga There is very little that one can add, at least nothing very insightful, to what has already And the media in some of our neighbouring countries have not been far behind in giving their verdict in their own way as to who were behind the planned killing of the army officers. In fact, several Indian print and electronic media have already identified by name the party and the individuals that, according to them, were behind the BDR massacre, well before the situation subsided. And of course there was a plethora of theories in Bangladesh on why and how it happened, and there was no dearth of articles both complimenting as well criticising the manner in which the government handled the situation. An interesting feature of the post BDR-carnage theorisation was the similarity of views of the two major parties that the killing was a well-planned operation aimed at striking at the very substance of the state. But that is where the agreement ended -- because both the parties had theories of their own on as to who might have been the masterminds that exploited the so-called grievances of the BDR soldiers, to reap the benefits of the outcome. Only recently the PM pointed fingers at the "evil force," meaning the defeated forces of 1971, for the BDR carnage. Although articulated many times, it bears repetition that the Pilkhana mayhem was one of the most brutal events in the annals of the country's history -- proving once again that we Bengalis can be the most violent and cruel creatures when we want to be. Even the rapacious Pakistan army did not kill so many Bengali officers in one operation, and even during the nine-month war of liberation only eleven of our brave officers were martyred. And this is perhaps the unkindest cut of all -- that couldn't have been delivered by genuine members of a disciplined force like BDR. Therefore, my personal conviction that the killings were done by some professional groups is reinforced with every passing day. Since it is the most traumatic event since 1971, and something that one hopes would never be repeated, it is imperative that we study the event dispassionately to draw lessons from it. This must be done in order to assess objectively as to what went wrong and why. But first of all it is necessary to remove some of the misconceptions about the issue that were created by debates and comments some of which betrayed a limited understanding of the matter. The fact that uninformed comments are worse than no comments at all, and can create more confusion and misunderstanding, has been reaffirmed once again after the 25/2 episode. It is important to keep in mind that in a highly charged situation, where emotions dictate actions, rationalisation becomes a very elusive attribute. By the same token, one's action or inaction should not be determined by the likely political dividends a particular stance might offer. Once that happens, human lives become mere pawns ready to be sacrificed to save the king. First of all, it must be understood that it if we characterise the Pilkhana incident as a mutiny or a rebellion, then it was without any political undertones, and in such a situation the prime objective of those that choose to defy the established order and discipline is not the wanton killing of their officers. Some have characterised the Pilkhana incident as a hostage situation. It is true that the killers had a list of demands, but one has not come across a situation where the hostage takers' bargaining chips -- the hostage(s) -- have been killed at the very first instance, as was the case in Pilkhana, where a large number of officers, if not all, were shot dead by the killers before giving the authorities the opportunity to respond to their demands. Therefore, it ought to be clear to all by now that the objective was not the fulfillment of the so-called demands, but taking the lives of officers. However, had the saga gone on longer, we may well have had a hostage situation in hand. And what might have been the motive? That is the million dollar question that we are waiting for the Anisuzzman Committee to find the answer to. The matter of "failure of command" has also been raised. It would be unfair to put the blame of failure of command entirely on the BDR chief alone. One feels that the buck should not stop with him. It is understood that many of the grievances, which are not of recent origin, had been put up to the government sometime or the other in the past. One would like to know what action the higher authorities had taken to mitigate the problems over all these years. If grievances have accrued over time, then no one single person can be held responsible for the carnage. The failure of command was at all levels. Reportedly, the PM was aware of some of the BDR demands and had also instructed relevant persons to take necessary action. If that was so, why the mutiny? Obviously, it was not mitigation of the problems that the killers were interested in. One also hears of the mutiny being solved "politically." This is a very strange comment that most likely stems from lack of clear perception of the matter. There was no political connotation, either of the act of killing or the way the incident was handled. Abstaining from use of force and the use of political figures to negotiate with the rebels does not validate the outcome as a political resolution. And neither were the so-called demands political. It was, at best, a solution where no shot was fired from the government side. Only time will tell whether it was the best solution, but we can at least dilate on the handling of the situation since this has been the most criticised action of the government. One has the benefit of hindsight in analysing the action of the government now. One must also keep in mind that the government decisions were dictated by information available at that particular point in time. And, therefore, it may be easy to pick holes in the decision with the benefit of post facto knowledge of the situation as was obtaining then.

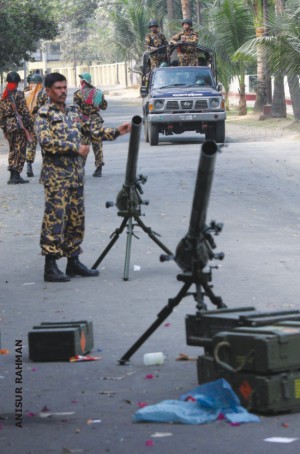

In a situation like what we had at Pilkhana, a fluid warlike environment, where there is neither enough of either intelligence or resources, and the commander is always fighting with time, it is cool-headed appreciation and practicable plans that set out the great leader from the ordinary. And it is only the outcome that can tell whether a particular decision was right or wrong. But no leader, least of all a military leader, ever starts off with a cent percent guarantee of success, because it is a very well known saying in the military that in spite of all the best preparations, the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry. The government has come under criticism from some quarters for not initiating immediate action, which, many feel, might have saved many lives. As per information available now, contrary to what was known initially, not all the officers were killed within the first few hours of the rebellion, but the killings were carried out in phases and over a period of time. The sliver of opportunity that existed in the first hour or so, to storm the BDR HQ and take the mutineers by surprise was lost either due to lack of intelligence or poor reaction by the commanders. That was the time when the rebels were disjointed and apparently discordant in their activities. Notwithstanding the availability of a large quantity of arms and ammo in the BDR armoury, a quick operation might have paid dividends. It is evident that there were no more than 50-60 in the rebel core group, with a few more joining later, some willingly and some under coercion. It was quite possible that had there been some sort of leadership, the rebels could have been subdued from within. By the same token, there was every possibility that if surprise was lost for whatever reason before the action was launched, there might have been more casualties, given, among other things, that there were several educational institutions inside the HQ compound. If that were to be so, then the quick operation would have been blamed for loss of lives. It was therefore a Catch-22 situation of sorts. But the fact is that no one can say with certainty that a swift action, with a small well-armed force, would not have succeeded, since such an operation was not undertaken in the first place. Not to take action was a strategic decision, which, one would like to assume, was the result of inputs from all agencies. And with hindsight one can find many flaws in it. But what has been most galling is the way the situation was handled at the tactical level, on the ground. And this has given rise to all sorts of speculative stories. Perhaps it was the illusion of a "political" solution that provoked the government to send out politicians as negotiators. And the way it was done was most unprofessional and callow. If there was any negotiation, what were the demands that the government put to the rebels? After all, no negotiation can be one-sided; unfortunately, it appears that this negotiation was so. The one question that the government will have to answer is: why were all the Pilkhana exits not blocked? The argument that the rebel soldiers would have used force to break out is not tenable because the government had already declared amnesty to the jawans. It was the government's duty to ensure that the large quantity of arms and ammo in the HQ was not pilfered out.

Was not surrendering of arms one of the pre-conditions of immunity, and should somebody in the administration not have advised as well as ensured that the most sensitive equipment were secured? The home minister went home on the night of February 25 assuring the nation that all the weapons had been secured and that she had the keys to the armoury with her. Why then have so many weapons gone missing?

Perhaps a few words are in order about the role of the media. It was through the media that we came to see the gory details of the massacre it was through the electronic media that the so called grievances were projected early on, on February 25, and the officers painted as demons and a bunch of dishonest men in front of the nation. It all turned out to be untrue eventually, but the damage had already been done. Media is a double-edged weapon, and the killers used it to their advantage effectively at the initial stage. What is surprising is that the authorities did nothing to counter that. One understands that the media, particularly the electronic media, thrive on sensational news. And whichever channel can get the most breathtaking and exciting events to its viewer the fastest, increases its revenue by that much. But if some TV channels had been unaware of the need for conflict-sensitive journalism, it is perhaps to do more with lack of understanding of the implications of their actions rather than lack of honest intention. Journalists often forget that it is objectivity and not neutrality that must guide reporting of events. Admittedly, objectivity is open to various definitions, but it must be kept in mind that no reporting should escalate violence in a conflict situation. It is well to remember, too, that journalists influence conflicts and objective journalism helps in attenuating a volatile situation. It should be remembered that, as Ross Howard says: "Professional journalists do not set out to reduce conflict. They seek to present accurate and impartial news. But it is often through good reporting that conflict is reduced." However, to determine what is good reporting requires not only experience, but an insight on the matter being covered. The scar of 25/2 will be hard to erase. But the lessons of it must not be lost on us. Corrective actions must be initiated immediately without waiting for the findings or recommendations of the investigation committees, since the lacunae in certain areas are so obvious as to brook no delay. Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan (retd) is Editor, Defence & Strategic Affairs, The Daily Star. |

been said and written on the BDR massacre. The opposition political parties have given their verdict on whom they think is responsible for it. And the AL has come out with theories of its own, courtesy the daily comments on the investigation by the minister for commerce. However, there are differing views on several important aspect of the matter in the Grand Alliance, particularly between the AL and its major component the JP, principally on how the matter should have been handled.

been said and written on the BDR massacre. The opposition political parties have given their verdict on whom they think is responsible for it. And the AL has come out with theories of its own, courtesy the daily comments on the investigation by the minister for commerce. However, there are differing views on several important aspect of the matter in the Grand Alliance, particularly between the AL and its major component the JP, principally on how the matter should have been handled.

We know now that the order for securing the exits was given by the PM herself. One wonders why it was not carried out. Why is it that the defaulter (s) have not been called to account for such gross negligence? Now we not only have missing jawans, there are also large number of weapons and ammunition that have gone missing. This has a very severe security implication for the country.

We know now that the order for securing the exits was given by the PM herself. One wonders why it was not carried out. Why is it that the defaulter (s) have not been called to account for such gross negligence? Now we not only have missing jawans, there are also large number of weapons and ammunition that have gone missing. This has a very severe security implication for the country.