Inside

|

Reaping What We Sow M. A. Sattar Mandal discusses the effects of climate change on crop production and food supply in Bangladesh Humankind has already seen an unprecedented food crisis in the second half of the first

decade of the 21st century. This has been characterised by a dramatic rise in almost all food prices to such a height that these went far beyond the purchasing power of the millions of poor consumers around the world, leaving them underfed and malnourished. The food price hike led to violent protests and political instability in many countries. As the FAO Director-General Jacques Diouf puts it, before food prices soared in 2007-08, there were 850 million malnourished people in the world, but that figure jumped by 75 million in 2007 alone, pushing these additional people into hunger and poverty. The speed at which world food prices soared was spectacular and it gave rise to speculation and panic buying at the country as well as individual consumer level. FAO's Food Price Index showed a 12 percent increase between 2005 and 2006, but increased by 24 percent in 2007, and further jumped by 50 percent up to July 2008. Although there have been bumper cereal harvests in the world in 2007-08, according to Diouf, food prices are likely to stay high for several years, putting the world's poorest countries at continued risk of food insecurity. Similar conclusions also came earlier from the International Food Policy Research Institute Director-General in December 2007. According to him, slow-growing supply, low stocks, and supply shocks at a time of surging demand for feed, food and fuel have led to such drastic price increases and that these high prices do not appear likely to fall soon.

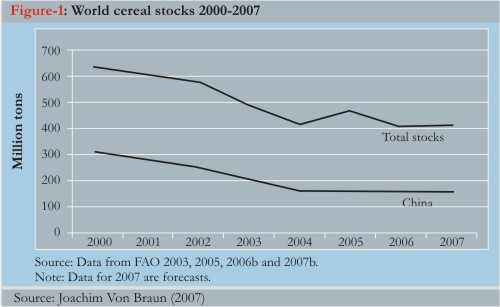

The climate change and bio-energy variables have further complicated the already delicate food security issues in developing countries. Many of these countries are resource-poor and highly vulnerable to natural disasters, and are struggling hard to reduce poverty and improve livelihoods of the poor. More importantly, climate change in South Asia will superimpose itself on the existing tenuous agricultural environment, significantly increasing production risk and rural vulnerability, particularly in regions that already suffer from poverty and hunger. Moreover, growing crops for bio-fuels directly competes for land devoted to food production and the recent price increases in the world's food markets are partly a result of this competition. World Cereal Production and Stock The declining stock of world cereal, which is a reflection of slow production growth relative to consumption, is also held responsible for food price escalation. IFPRI analysis shows that the world's total cereal stock also declined during the 2000s, especially wheat stock which dropped to its lowest level since early 1980s. The stock depletion is largely due to significant fall in stock in China between 2000 and 2004, which accounts for about 40 percent of total world stock (Figure 1). Diversion of food crops, including sugarcane, maize, oil palm and canola, is affecting food supply as these also provide feedstock for bio-fuel production. Approximately 90 percent of liquid bio-fuel ethanol is produced from maize in the United States and sugarcane in Brazil. It is feared that greater profit margins and a growing demand for bio-fuels may encourage farmers to grow bio-fuel crop acreage, causing a decline in cereal foods and ultimately triggering off food prices. Soaring International Prices The skyrocketing of food prices, especially rice prices, since late 2007 has been attached to the imposition of restrictions on rice export by some major rice exporting countries like India, Vietnam, Cambodia, China and Egypt. A recent analysis by CPD shows that India's decision for rice export ban prompted Vietnam to put temporary ban on her rice export and that this contributed to the creation of an artificial supply shortage shooting the international rice price to $1,100 per ton in May 2008. This was the time that Bangladesh and Philippines were desperately trying to buy rice at any cost. As the rising food prices continue to hit the world's poor, rice future market and speculation are blamed for the price hike. The recent IFPRI forum reports investment of billions of dollars by institutional investors in U.S. commodity futures markets as evidence of increasing speculative activity in global food markets.

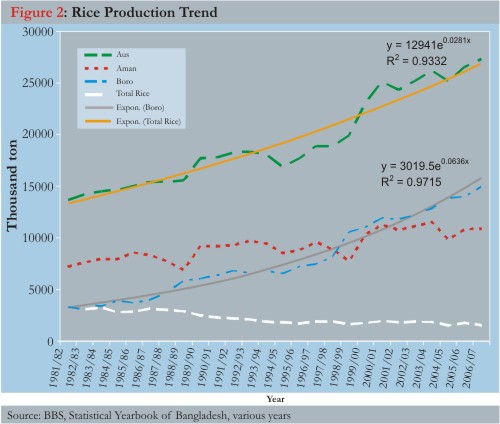

Production Scenario FAO/WFP mission estimates 17.54 million tons of boro rice. The production of main staple rice has shown a long term trend growth of 2.8 percent per annum over the period 1981-82 to 2006-07. The main contributor has been the irrigated boro rice production, which showed about 6.3 percent annual growth during the same period. Currently, boro rice accounts for about 60 percent of total food grain production. While aus rice production declined over time, moderate growth in aman rice, accounting for around 30 percent of food grains, also contributed to the accelerated production. It is notable that boro production in 2007-08 increased by 18.87 percent over the previous year and this largely contributed to the rise in total food grain (rice and wheat) production by 6.13 percent during this time. Wheat production in 2007-08 also increased by 14.5 percent over 2006-07, indicating a reversal to the decreasing trend of the past. The significant jump in 2008 boro production was mainly due to favour-able weather conditions, timely planting, better care for input application and inter cultural operations by farmers, hard work and vigilance of the Agricultural Extension officials, diesel and electricity supply, and above all extra efforts and constant monitoring by the Ministry of Agriculture. Import of Food and Domestic Rice Price A recent analysis by CPD on food imports and food prices in Bangladesh reveals a number of interesting findings. Firstly, most of the rice imported to Bangladesh comes from India. Indian policy related to the minimum export price of rice and then a ban on rice export in March and April 2008 contributed to the sharp rise in rice prices in Bangladesh. Secondly, it also to some extent prompted Thailand to increase its export price of rice. Thirdly, there is a general correspondence between wholesale and retail price of coarse rice in Bangladesh domestic market, and, as the data shows, the largest difference in prices prevailed during July 2005 to end of 2006. When the rice prices started to shoot up from about mid July 2007, the price differences between wholesale and retail market narrowed significantly, indicating that at a time of soaring rice prices people rush to buy immediately from retail market even at a higher price. Availability of Food Access to Food and Consumption Pattern The most disturbing picture of food consumption appears when comparison is made between various income groups of people. The lower income groups (less than Tk 4,000 per month), who constitute about 45 percent of households, consumed hardly two-thirds of the quantity of foods consumed by the upper income groups (Taka 20,000+ per month), constituting only 6 percent of households. The difference was most conspicuous due to much less consumption of nutritious food i.e. fish, meat, eggs and fruits by the lower income groups. It implies that even before the food price hike, despite significant increase in food production a large proportion of people consumed much less food than required for healthy life.

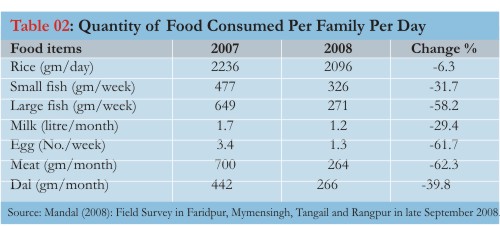

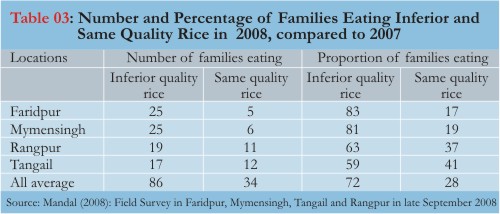

Impact of Price Hike on Food Security In September 2008, a daily wage could hardly buy 4 kg of coarse rice (Figure 3). Evidently, there has Been wage inflation together with rice price inflation, but the rise in coarse rice prices has been faster than the rise in wage rates, therby threatening food security of the poorest of the poor. Recent estimates by the World Bank suggest that the impact of the food price shock has likely negated some (but not all) of the reduction in poverty brought about by economic growth between 2005 and 2008. But this is at the macro level. What this price hike means at the household level is worth investigating. A recent analysis by Bayes and Hossain based on a nationwide survey reveals that a 50 percent increase in rice price takes away 25 percent of poor household's income, meaning a negative effect on meeting other basic needs. This author's quick survey of 120 households (60 rickshaw pullers and 60 agricultural wage labourers) in September 2008 shows that average quantities of rice and protein rich foods have significantly fallen in 2008, compared to 2007 and that 72 percent families have not only consumed lesser foods but also lower quality rice (Tables 2 and 3). This finding is also corroborated by a recent survey of 250 landless farmers, day labourers, rickshaw pullers and small shop-keepers by Raihan. Both these surveys indicate that the poor are sacrificing consumption of whatever little high value foods they could afford before the price hike in order not to reduce rice consumption much, which is already at low levels. A FAO-supported NFPCSP project's initial estimates of urban food expenditures based on HIES 2005 data implies that the already monotonous diet of poor households would now have become even more monotonous with mainly rice and little scope for dietary diversity. Climate Challenge on Food Security On top of all these, challenges of climate change i.e. floods, droughts, cyclones, etc are superimposed, meaning that the country will be exposed to a range of disaster risk and vulnerability and that the ongoing efforts to reduce poverty and hunger might be slowed to some extent.

But what do these climate challenges mean for the country? According to Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) prediction, global temperatures will rise between 1.8 degrees and 4 degrees (celsius) by the last decade of the 21st century. As the Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (BCCSAP) 2008 puts it: "Monsoon rainfall will increase, resulting in higher flows during the monsoon season in the rivers, which flow into Bangladesh from India, Nepal, Bhutan and China. Global warming will result in mean sea level rises between 0.18 and 0.79 metres, which could increase coastal flooding and saline intrusion into aquifers and rivers across a wide belt in the south of the country, although income sources and expansion of social safety net programs of the government. But that has diminished to some extent. An analysis of a nationwide time series data shows that an agricultural labourer's daily wage that was most of the area is protected by polders. Rainfall is predicted to become both higher and more erratic, and frequency and intensity of droughts are likely to increase, especially in the drier northern and western parts of the country.” Among the most vulnerable countries to floods and cyclones, Bangladesh is ranked as the most vulnerable country to tropical cyclones and the sixth vulnerable country to floods. The BCCSAP report says that there will be increasingly frequent and severe floods, tropical cyclones, storm surges, and droughts, which will disrupt and displace millions of people from coastal regions, making them environmental refugees, unless existing polders are strengthened and new ones are built. How will the climate changes affect agriculture and livelihoods in Bangladesh? Negatives impacts of climate change on Bangladesh agriculture as reported in various documents can be summarised as follows: (i) extended flooding of arable narrows the scope for crop production, especially in the vast low land areas; (ii) increasing temperature will lead to increased evapotranspiration and droughts, causing water scarcity for irrigation and domestic uses in north-west Bangladesh; (iii) increased inundation and salinity intrusion, limiting crop cultivation with the existing varieties, especially in the coastal regions. Loss in terms of land degradation and arsenic contamination of soil and water is becoming a major concern (Heikens, 2006; Ahmed, 2007); (iv) increased intensity of flash floods in Meghna basin and north eastern haor region, damaging standing boro rice crop; (v) increasing loss of land to river erosion, reducing land-based livelihood opportunities, and increased drainage congestion and water logging due to sedimentation of rivers, limiting production options for the char dwellers.

In quantitative terms, IPCC estimates that, by 2050, changing rainfall patterns with increasing temperatures, flooding, droughts and salinity (in coastal belt) could cause a decline in rice production in Bangladesh by 8 percent and wheat by 32 percent, against 1990 as the base year. At the country level, studies using crop models with various assumptions about temperature and CO2 level predicted a general decline in yields and output of rice crop in all seasons in 2050, compared to base year 1990, the rate of reduction varying between crops and models used (Karim, et al., 1996). The recent estimates using different models with changed assumptions predicts for 2050 reduction in production by 1.5-25.8 percent for aus rice, and 0.4-5.3 percent for aman due to the effect of high temperature. For boro rice, production could be increased by 1.2-9.5 percent, assuming the temperature would not exceed the 350 C threshold limit for rice production. Suggested Actions for Food Security and Climate Change Adaptation Let us first discuss the possible areas of interventions with respect to food grain production and nutrition. Agricultural technology generation must be given the top most importance, which needs energising the agricultural research system, especially plant and animal breeding research. With scanty resources and manpower, plant breeding research at BRRI has made commendable achievements in developing and releasing a number of climate adjusting varieties such as drought escaping aman varieties, BR-33 suitable for Monga areas, BR-42, 43 as draught resistant aus varieties, BR- 40, 41 as salt tolerant aman varieties and BR-47 as salt tolerant boro varieties for the coastal areas, and BR-46, 22, 23 as post- flood late planting aman varieties for areas where flood water recedes late. BRRI in collaboration with IRRI and other international institutions has been also engaged in developing submergence-tolerance aman variety (BR-11, Sub-1), salt-tolerant varieties for boro, cold-tolerant variety, high tide and low tide variety for coastal belt, and early and late drought-resistant aman varieties. These are promising ventures for supporting climate adaptation efforts, which deserve upscaling of laboratory support, skill development, manpower mobilisation and retention, and operational finance. Along with the national research systems, to counteract rising food prices, international research systems should be ready to invest more heavily in agricultural science and technology to increase agricultural production on a global level. Bangladesh already faces formidable challenges of keeping up the present momentum of food production in a declining land and water resource situation. Arable land is decreasing at about 1 percent annually, although a proportion of cultivable land is being shifted from crop cultivation to more profitable enterprises such as pond fishery, livestock farming and agro-forestry. This is the kind of transformation we encouraged in the past in order to bring about diversification of agriculture. But the looming food crisis forces us to think hard about how best to protect rice lands from being converted into non-agricultural uses. Possibilities of earth filling along the sea, organised community housing and enactment of laws restricting conversion of agricultural land for other purposes can be explored. Soil health is in jeopardy due to loss of organic matter content and continuous use of unbalanced chemical fertilisers for irrigated rice production. Fertiliser shortage is held responsible for the looming food crisis. The recent jump in fertiliser prices are likely to discourage millions of Bangladeshi small farmers to apply required doses of fertilisers, especially the essential soil nutrients like phosphate and potash, whose prices have sky rocketed. To ensure optimum use of TSP and MP fertilisers for maintaining good harvests in the coming seasons, additional subsidies on non-urea fertilisers or at least recasting subsidies on urea should be attempted along with further improvement of fertiliser delivery mechanism. A drop in profits from irrigated rice farming is likely due to rise in input cost. The current high price of paddy gives a reasonable incentive to farmers with marketable surplus but those who are the net buyers of rice are hard hit by high rice price (they are 62 percent in number but operate only 27 percent of land). Bayes and Hossain identified the surplus farmers as those cultivating more than one acre, and those below one acre are deficit producers. Recent Sample Survey of Agriculture (2005) shows that farmers above 1 acre constitute 38 percent of total number of farm households but they cultivate 73 percent of land and thus produce about three-fourths of total rice in the country. Therefore, for sustaining high incentives of surplus rice farmers and for maintaining the current rice production growth momentum, paddy price must not fall much below the present level. Otherwise, the sustainability of irrigation water market that has proved to be the key driver in accelerating Boro rice production in Bangladesh will be hampered. For long term sustainable growth in food production, there must be technological support to achieve productivity gains through reducing yield gaps, supplying quality inputs, and assuring good price of output. Especially, water productivity, which is much less than in neighbouring countries, has to be increased through dissemination of water saving technologies, on-farm water management training and wherever possible promoting rain water harvest. Sustaining production in favourable ecologies and modernising production system in unfavourable eco-systems call for massive technological support. Bangladesh has 41 percent of land as agro-ecologically constrained regions, which include deeply flooded areas, char land, flush flood areas, coastal tidal surge and salinity prone areas and hill agriculture. These areas have difficult soils, poor communication infrastructure, disperse agricultural extension network, poor marketing facilities and high incidence of poverty, and thus these areas need special investment priorities. Especially, attempts must be made to increase cropping intensity by bringing huge seasonal fallow lands available in the north east, southern and some parts of northern regions. Since food grain prices are going to stay high for some time, the country has to upscale and broaden its safety net programs to rural areas to protect the poor consumers and ensure food security for all. The current National Food Policy Plan of Action emphasizes supplementation and fortification for balance nutrition. While this can be there, more important approach to ensuring food security will be to pursue food-based approaches through production as well as dietary diversity. The country's climate change action plan stresses on adaptation to climate change. No doubt, structural measures like cyclone shelters, coastal embankment and polders are needed to protect life and properties from natural disasters. Simultaneously, best practices from programs like HKI homestead food production system for char land dwellers, BARI homestead vegetable production in droughty high barind areas, and UNDP-DFID community based adaptation program should be widely replicated in similar areas. Other programs like tree plantation, coastal forestation, agro-forestry, water conservation, and rain water harvest should be promoted. In such awareness building and technology dissemination, the huge potential of Agriculture Extension Department should be properly utilised.

Institutional capacity to deal with climate change variables must be strengthened. This will include mainstreaming climate change adaptation in government policy discourse, mobilisation of trained manpower, awareness building, and incorporation and upgrading of university curricula on climate studies and research. There is also an urgent need of establishing ecosystem based studies and database so that the impact of climate change on crops, livestock, fishery, biodiversity and natural resource management can be appropriately monitored. Saarc initiatives are at work to address climate change and food security challenges through facilitating consultations and development of projects at the regional level. Bangladesh should actively engage itself in these regional efforts and for this the government should involve the scientists, academics and civil society think tanks. Saarc Agriculture Centre should be positioned as an anchor institution so that it can play greater role in facilitating regional dialogues and country-specific information on agriculture and food security matters. Professor M. A. Sattar Mandal is Vice-Chancellor, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh. |