|

Cover

Story

Eating

Away Our Health

One

of the biggest casualties of urbanisation in this country

has been the quality of life, a large part of which includes

good health. With a culture of malpractice seeping into every

sector and level it is hardly surprising that it has reached

the most important of our basic needs--food. With ineffective,

outdated laws, lack of enforcement and institutional corruption

there is an overwhelming indifference to consumer rights and

public health. Dishonest food manufacturers and traders are

having a free reign in the market adding harmful substances,

selling contaminated food or tampering with the original content

of the food item. The government has various bodies to control

food quality. But why aren't they doing their job? One

of the biggest casualties of urbanisation in this country

has been the quality of life, a large part of which includes

good health. With a culture of malpractice seeping into every

sector and level it is hardly surprising that it has reached

the most important of our basic needs--food. With ineffective,

outdated laws, lack of enforcement and institutional corruption

there is an overwhelming indifference to consumer rights and

public health. Dishonest food manufacturers and traders are

having a free reign in the market adding harmful substances,

selling contaminated food or tampering with the original content

of the food item. The government has various bodies to control

food quality. But why aren't they doing their job?

Every

now and then we are shocked by media reports of ingenious

forms of adulteration of food that we consume regularly. According

to IPH (Institute of Public Health) more than fifty percent

of food samples they have tested are adulterated. Food colouring

is a form of adulteration. A toxic artificial dye is used

to colour fruits and vegetables such as melons and tomatoes

to give them a rich colour.

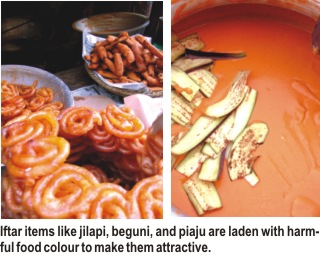

Ironically even food colour is being adulterated. Substandard

food colour is finding its way into many types of food. This

includes the reddish jelapi, and the saffron beguni,

peaju or alur chop. Candy, chips, ice cream,

chewing gum and even biryani may contain large amounts

of poor quality food colour. Textile dyes such as carbide

and ethopene are also being used to colour different iftar

items to attract customers. Urea fertiliser is used while

frying muri to whiten it. Cyanide is used to give

mustard oil extra bite.

Ironically even food colour is being adulterated. Substandard

food colour is finding its way into many types of food. This

includes the reddish jelapi, and the saffron beguni,

peaju or alur chop. Candy, chips, ice cream,

chewing gum and even biryani may contain large amounts

of poor quality food colour. Textile dyes such as carbide

and ethopene are also being used to colour different iftar

items to attract customers. Urea fertiliser is used while

frying muri to whiten it. Cyanide is used to give

mustard oil extra bite.

Brick

dust is mixed with chilly powder and a poisonous yellow colourant

is mixed with turmeric powder to make it more yellow. Water

and salt are also mixed with these spices to increase weight.

Mangoes, jackfruit, lychees, watermelon, pineapple, papaya

and bananas are artificially ripened using a carcinogenic

chemical called ethylene oxide. In bananas, another chemical

called Calcium Carbide is used which happens to be a sprayed

Acetile-gas that releases heat, says Dr. Golam Mowlah, Ph.D.,

the Professor and Director General of Institute of Nutrition

and Food Science, Dhaka University.

"We

should avoid eating fruits and vegetables which are not seasonal"

says Golam Sarwar, Public Analyst of DCC's Public Health Laboratory

(PHL), "as the chemicals are used only when the fruits

are not seasonal, because chemicals also cost. It is also

better to avoid grind spices or grind it in the grinder, which

is available in the kitchen markets.

Dalda,

a vegetable based fat used for cooking is an example of one

of the worst cases of adulteration. "Our stomach's temperature

is 37 degrees Celsius and the melting point of dalda

is 54 degree Celsius. Thus there is no way that dalda

can be absorbed by the body," says Sarwar.

If

you think fish is a healthy option think again. Many fish

sellers spray fish with 'formalin' -- a chemical usually used

for preservation of tissues. This chemical is mainly used

with imported fish and it makes the fish stiff and keeps them

looking 'fresh' for a longer duration. If

you think fish is a healthy option think again. Many fish

sellers spray fish with 'formalin' -- a chemical usually used

for preservation of tissues. This chemical is mainly used

with imported fish and it makes the fish stiff and keeps them

looking 'fresh' for a longer duration.

Research

has found that there is 'ecoli' in almost all our food items.

Ecoli can be fecal, skin, hair etc. If proper sanitation codes

of conducts are to be followed, these forms of contamination

must be totally absent in all food items.

Cooking

oil that is so commonly used to deep fry items should only

be used once but many food vendors and restaurants recycle

burnt oil. Once the oil is used for cooking, it becomes oxidised.

The more the oil is used, the more pre-oxide is created which

is really harmful for the body. This gets more poisonous with

continued usage.

Everything

has a standard but it must be free from adulteration, artificial

colour and contamination says Dr. Mowlah. "There is a

sanitary code, the Good Manufacturing Procedure (GMP), which

is usually used in manufacturing items. This practice can

also be used for food items and should be strictly followed

as much as possible. There is also a Hazard Analysis Critical

Control Point (HACCP) code which deals with maintaining microbial

quality control. This too is a part of the sanitary code or

Good Manufacturing Practice". Everything

has a standard but it must be free from adulteration, artificial

colour and contamination says Dr. Mowlah. "There is a

sanitary code, the Good Manufacturing Procedure (GMP), which

is usually used in manufacturing items. This practice can

also be used for food items and should be strictly followed

as much as possible. There is also a Hazard Analysis Critical

Control Point (HACCP) code which deals with maintaining microbial

quality control. This too is a part of the sanitary code or

Good Manufacturing Practice".

"The

main question is why will we go for deviation from the natural

process?" says Mowlah. "We have to start to go for

organic food. We have to make propaganda against the artificial

food items".

The business

of maintaining food quality is a little confusing considering

the fact that various government bodies handle the different

categories of food and food testing. This includes DCC's public

health department, BSTI (Bangladesh Standards Testing Institution)

which frames standards of food products and also conducts

testing and the Institute of Public Health. Apart from that

various ministries have jurisdiction over various food items.

For example, the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock monitors

fish and meat quality, while food grains are under the Ministry

of Food.

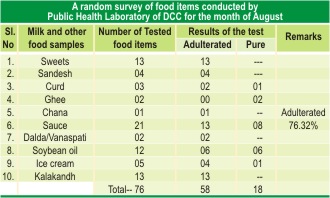

The bulk

of the responsibility, however, for most of the monitoring

and control of food quality, seems to lie with the Dhaka City

Corporation (DCC). Apart from issuing trade licenses to manufacturers,

the DCC through its Public Health Laboratory conducts testing

of samples after which it can take punitive action against

the offenders. Samples include packaged, bottled or canned

food both local and foreign as well as food sold on the streets.

Each of the ten zones that the DCC deals with has a team of

one assistant officer, two inspectors and two sample takers.

These teams survey the market and pick out items suspected

of adulteration. The samples are then tested in the DCC lab

and the public analyst compiles the findings. Every few weeks

the public analyst submits a statement of the findings to

the DCC and based on this the inspectors serve show cause

notices to the offending party. If the offender does not take

heed of the notice, the inspector, through the magistrate

can file a case and a penalty is imposed. All this sounds

like a foolproof system for catching sellers of adulterated

food but there are several flaws in this mechanism as DCC's

public analyst Md. Golam Sarwar points out making it easy

for the culprits to go on with their fraudulent business.

First

of all the Pure Food Act 1959 that prosecutes offenders of

this kind has not been amended for the last 12 years. The

penalty under this Act for food adulteration is a ludicrously

low amount of Tk 200. "We have submitted a proposal for

the penalty section (of the Ordinance) to increase the fine

from Tk 5,000 to Tk 5 lakh," says Sarwar. "Unless

the fine is high enough to scare the offenders, such laws

cannot act as deterrents". The last time the Ordinance

was amended was 1993. The Prime Minister at a cabinet meeting

on November 1 endorsed the draft of the proposed Bangladesh

Pure Food (Amendment) Act 2004. First

of all the Pure Food Act 1959 that prosecutes offenders of

this kind has not been amended for the last 12 years. The

penalty under this Act for food adulteration is a ludicrously

low amount of Tk 200. "We have submitted a proposal for

the penalty section (of the Ordinance) to increase the fine

from Tk 5,000 to Tk 5 lakh," says Sarwar. "Unless

the fine is high enough to scare the offenders, such laws

cannot act as deterrents". The last time the Ordinance

was amended was 1993. The Prime Minister at a cabinet meeting

on November 1 endorsed the draft of the proposed Bangladesh

Pure Food (Amendment) Act 2004.

The age-old

ordinance does not include many new products that are now

available in the market but were non-existent in 1959. This

includes the wide range of junk food that is so popular amongst

present generation consumers. Though use of formalin in fish

is a well-known phenomenon PHL is not doing anything about

it. "The Pure Food Ordinance 1959 doesn't have fish as

a food item. So, we cannot go for prosecuting traders involved

in mixing formalin with fish even if we manage to get hold

of them," Sarwar, Chief Public Analyst of PHL, points

out.

But just

having an intimidating law is hardly enough to deter unscrupulous

traders from tampering with food if the monitoring system

is not efficient. "Food adulteration can be due to many

things", explains Sarwar, "it can be through mixing

in harmful chemicals or colourants, due to pesticide residue

or microbial contamination". To find out the exact component

being mixed or causing the contamination requires sophisticated

testing with state of the art equipment which the present

Public Health Lab does not have says Sarwar. The lab for instance,

has no facility to test drinking water or the chemical colours

used in various items. He estimates that such equipment would

cost around 20 to 25 crore taka but it is an investment that

is crucial to ensure food quality. Training of lab workers

is also important and Sarwar believes that such personnel

should be trained abroad. "Technical expertise and the

lab facilities must be upgraded," he remarks.

Although

the DCC has a major share of the responsibility to monitor

food quality in the city and punish offenders, the public

analyst feels that it must be given more attention by the

ministry to make sure that the system of quality control works.

"The mayor and other officials must give priority to

the food control activities". Co-ordination among various

government bodies that deal with food quality is also needed.

At present various bodies deal with different food categories.

The DCC Health department is concerned with food items sold

within the city while BSTI issues approval seals to products

including bottled water. But BSTI tests only the first batch

of a product. They don't check the consequent batches which

may not maintain the same quality as the first batch. If the

DCC health department had the authority and capability to

conduct continuous testing of following batches after trade

licenses are given out (which the DCC does after approval

from BSTI) then there is less scope of substandard food being

sold legally in the market. Golam Sarwar suggests that a DCC

food-testing certificate be made compulsory for all traders

of food items. "Testing can be done 3 times; first when

the trade license is applied for, secondly to monitor the

production and for a third time when the license needs to

be renewed". In the case of imported food items, says

Sarwar, often traders bring in products from abroad through

LCs with banks and then the food items are kept in the bank's

storage. There is no monitoring of the storage facilities

and often the goods lie in the storage rooms for months exceeding

expiry dates. Once the traders pay off the money to the banks

the goods are released and sold in the market with no control

over their quality. Although

the DCC has a major share of the responsibility to monitor

food quality in the city and punish offenders, the public

analyst feels that it must be given more attention by the

ministry to make sure that the system of quality control works.

"The mayor and other officials must give priority to

the food control activities". Co-ordination among various

government bodies that deal with food quality is also needed.

At present various bodies deal with different food categories.

The DCC Health department is concerned with food items sold

within the city while BSTI issues approval seals to products

including bottled water. But BSTI tests only the first batch

of a product. They don't check the consequent batches which

may not maintain the same quality as the first batch. If the

DCC health department had the authority and capability to

conduct continuous testing of following batches after trade

licenses are given out (which the DCC does after approval

from BSTI) then there is less scope of substandard food being

sold legally in the market. Golam Sarwar suggests that a DCC

food-testing certificate be made compulsory for all traders

of food items. "Testing can be done 3 times; first when

the trade license is applied for, secondly to monitor the

production and for a third time when the license needs to

be renewed". In the case of imported food items, says

Sarwar, often traders bring in products from abroad through

LCs with banks and then the food items are kept in the bank's

storage. There is no monitoring of the storage facilities

and often the goods lie in the storage rooms for months exceeding

expiry dates. Once the traders pay off the money to the banks

the goods are released and sold in the market with no control

over their quality.

Bangladesh

Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI), the national standards

body, is an autonomous organisation under the Ministry of

Industries. BSTI performs the task of formulation of national

standards of industrial, food and chemical products. Quality

control of these products is done according to Bangladesh

Standards. Till date BSTI has come up with over 1800 national

standards of various products adopting more than 132 International

Standards (i.e.ISO) and food standards set by the Food and

Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

BSTI certifies

the quality of commodities including food items for local

consumption, which applies both for export and import. Currently,

142 products are under compulsory certification marks scheme

of BSTI including 54 agricultural and food items.

Food

items that are subject to compulsory certification marks are

: pineapple juice, chillies whole and ground, turmeric powder,

wheat bran, whole milk powder and skimmed milk powder, white

bread, biscuits, lozenges, tea, fruit squashes, jam, jelly

and marmalade, fruit vinegar( sirka), butter, soyabean oil,

sugar, flour, fruit or vegetable juice, carbonated beverages,

fruit syrup, honey, liquid glucose, dextrose monohydrate,

toffee, canned and bottled fruit, fruit cordial, sauce(fruit

and vegetables), tomato juice, tomato paste, pickle, concentrated

fruit juice, tomato ketchup, canned pineapple, infant milk

food, butter oil and ghee, mustard oil, noodles, iodised salt,

palm oil, drinking water, natural mineral water, ice cream,

chips/crackers, laccha semai, pasteurised milk, soft

drink powder, condensed milk and so on.

" Important

essentials that may be adulterated and contaminated are included

in the BSTI mandatory list," says ABM Abdul Haq Chowdhury,

Director General (DG) of BSTI. Important

essentials that may be adulterated and contaminated are included

in the BSTI mandatory list," says ABM Abdul Haq Chowdhury,

Director General (DG) of BSTI.

"Other

commodities like food colour is excluded due to not having

quality machinery for testing," adds the DG.

BSTI has

also made it mandatory to mention six specific facts regarding

the product on the package. This includes the date of production,

date of expiry (best before use), net contents or weight,

address of the producers or marketing companies, maximum retail

price (MRP) and the ingredients.

"Consumers

have a right to know what is inside the product," says

Chowdhury. "There are instances of companies stating

inflated weights or quantities of the product than what is

actually there."

According

to BSTI sources some companies import expired ketchup and

food products but because the address of these importers opened

L/Cs under false address.

Chowdhury

points out that there are also instances where the media is

allowing advertisement of products, the certificates of which

have been cancelled by BSTI. Certificates of condensed milk

manufacturers for example, have been cancelled by BSTI whereas

the media is allowing advertisement of these products ignoring

BSTI objection.

"People

need to be conscious and aware about their health; we cannot

simply take whatever is produced, even BSTI seals are printed

without our approval, but we have no strong laws or punishment

against the culprits," says the DG.

BSTI sets

standards of products but they cannot enforce the standard

in the market. BSTI collects random samples from the factories

and also buys products from the market to test. If they find

sub-standard product they do not have the power to take action

against the company or the industry.

The BSTI

Ordinance 1985 has been amended to Bangladesh Standards and

Testing Institution (BSTI) (amendment) Act 2003 for consumers'

protection against low quality products. Under the BSTI amendment

Act 2003, BSTI inspectors have been included in the mobile

court team along with Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) inspectors

under the Home ministry.

According

to a BSTI press release, from October 17 to October 28 BSTI

fined Tk. 6,91,000 for keeping adulterated products like biscuits,

oil, ghee, laccha semai, lozenges, drinking water,

bread and also filed cases against the owners of the shops

and industries.

Established

in 1953, the Institute of Public Health (IPH) organises its

activities of quality control of drugs, food and water, production

of vaccines, intravenous fluids, antisera and diagnostic reagents,

diagnosis of infectious diseases and related research facilities.

IPH

is formed to assist the government to prevent and control

major health hazards caused by contaminated and adulterated

food and water. Besides this it organises training programmes

in the field of diagnosis, control and prevention of infectious

diseases and food and water safety. It also conducts various

research activities in related fields of public health, and

to collaborate and co-operate with other national, international

organisations and agencies in the promotion of public health. IPH

is formed to assist the government to prevent and control

major health hazards caused by contaminated and adulterated

food and water. Besides this it organises training programmes

in the field of diagnosis, control and prevention of infectious

diseases and food and water safety. It also conducts various

research activities in related fields of public health, and

to collaborate and co-operate with other national, international

organisations and agencies in the promotion of public health.

"We

don't collect samples of food ourselves. Sanitary inspectors

in pouroshobhas and districts send samples, which

the inspectors suspect as adulterated or contaminated. IPH

sends back these test reports to the district civil surgeon

and pouroshobha chairman," says Amirul Islam,

Director of IPH.

IPH tests

107 food items of which almost all items are either adulterated

by mixing low quality products or contaminated by using toxic

chemicals, according to the findings of IPH.

Obviously

consumer rights protection has to be made popular and effective.

The CAB (Consumers Association of Bangladesh), the only private

organisation working in this arena, has been lobbying for

the last ten years for an effective law that would enable

the government to prosecute the crime of food adulteration.

The law titled Consumers Rights Protection Act, which was

basically drafted by CAB, has already been approved in principle

by the cabinet. "The file is now lying with the Commerce

ministry from where it will go to the Law ministry and then

it will be examined by the parliamentary committee before

it is finally approved by the parliament and made into an

act," informs Quazi Faruque, general secretary of the

CAB. Faruque is hopeful that fighting adulteration of food

will be a lot easier once the proposed act comes into effect.

The

health effects of having such adulterated food have not been

researched but health experts agree that over prolonged periods

such consumption amounts to slow poisoning. Many of these

substances are cancer causing and almost all of them have

adverse effects on the digestive system affecting the liver,

heart and other vital organs. In a scenario where the penalty

for such crimes of adulteration is either negligible or unenforceable

and where substandard food has become the norm rather than

the exception, the public is powerless and vulnerable. The

government, with enough political will, has all the means

to bring about change in the quality of food and therefore

of life.

--AASHA

MEHREEN AMIN

AVIK SANWAR RAHMAN

SHAMIM AHSAN

and IMRAN H. KHAN

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|