Inside

|

In the beginning Hameeda Hossain reminisces about Forum's early days and the challenge of bringing out a hard-hitting weekly journal at the height of martial law in the Pakistan era

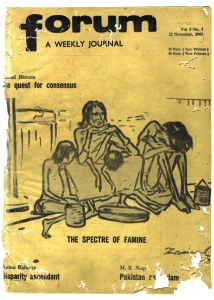

In the sixties, the English language weekly Forum exercised a political influence far beyond its short life span (from November 22, 1969 to March 20, 1971) and its low circulation (of no more than 2,000 print copies). This was because it gave voice to the national aspirations of the Bengali people and questioned the validity of a militaristic, theocratic state, and at the same time tried to articulate the concerns of the working class and the peasantry. Columns on economic disparity and political disenfranchisement by leading academics, political analysts, and activists made an important contribution to the ongoing debates on state and nation in Pakistan. Our final editorial of March 20, 1971 was titled "Options for a Sane Man." A few days later, the military resorted to the insane option. Forum's last issue of March 27, 1971 was still at the printers when the Pakistan military launched Operation Searchlight. The reincarnation of Forum as an English monthly in 2006 may not be an intellectual legacy per se. Cataclysmic changes have taken place in Bangladesh in the last thirty years, and a generational change in style and content is to be expected. But poverty, political conflicts, inequality, and violence continue to haunt Bangladesh. And democracy continues to mean different things to different groups, depending upon our location in the power structure. The established view in the sixties was that Ayub Khan had created a fool-proof system of support for military rule in the "Basic Democrats" elected in rural constituencies, and comparador businessmen who had benefited from public sector financial patronage. Cultural integration through intellectual and cultural exchange was touted as the answer to the growing estrangement between the two parts of Pakistan. Official celebrations for "a decade of development" seemed in order. But East Pakistan was in ferment -- cultural, political, intellectual. Protests against military rule, against economic disparity and cultural controls had grown louder. In 1964, Dhaka University students had boycotted their convocation because it was to be inaugurated by Ayub Khan's governor, Monem Khan. A new literature of protest was created even as artists, writers, and intellectuals went on the streets to protest the ban on Tagore's songs or the wearing of the teep by women broadcasters on TV. The insecurity generated by the war with India in 1965 certainly created little confidence in a remote-control system of defence located in the western wing. In 1966, when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman announced his six-point proposal for autonomy as a national solution, and the Awami League barn-stormed through the countryside to further its demand for parliamentary elections, the political climate was electrified. Mass arrests of political leaders and cultural activists, curbs on press freedom, filing of the Agartala Conspiracy Case against Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and other incidents led to an irreconcilable alienation of the Bengali people from the Pakistani state. Political scientists, economists, and other professionals justified these aspirations for autonomy as a means towards economic and social justice and political democracy in East Pakistan. Rehman Sobhan, then a teacher at Dhaka University, had popularised the notion of the "two economies of West and East Pakistan" in a seminar in Lahore which was widely reported in the media. Kamal Hossain had taken up the legal defence of democratic rights of political detainees, challenged the proscription of Ittefaq and Sangbad, and assisted in the defence of the accused in the Agartala Conspiracy Case. On their return from their studies in the fifties, both men had engaged with a liberal, progressive community of academics, journalists, and professionals in discussions on national political developments. They chose public forums and newspaper columns to explain the possibilities of economic and social justice within a secular framework in East Pakistan. The precursors for Forum were to be found in New Values, a literary-cultural journal edited by Professor Khan Sarwar Murshid, who was at the time a Professor of English in Dhaka University, and in the pamphlets published by members of an informal group formed in 1961 that called itself National Association for Social and Economic Progress (NASEP). It published three pamphlets: on The Challenge of Democracy, authored by Kamal Hossain, on The Challenge of Disparity by Rehman Sobhan, and on The Challenge of Education by Musharraf Hussain. The NASEP group which included Professors Abdur Razaque, Musharraf Hussain, Badruddin Omar, Salahuddin Ahmed, Zeaul Haque Tulu, and Advocate Kamruddin Ahmed, had hoped that these pamphlets would mobilize public opinion on the issues of political representation, economic disparity, and democratic freedom in East Pakistan. By 1965, the informal group included several journalists as well, such as Ahmedul Rahman and Muyeedul Hasan. They discussed the possibility of starting a political weekly. Eventually, Kamal Hossain, Rehman Sobhan and Zeaul Haq Tulu decided to apply for permission to publish a political weekly under the Press and Publication Ordinance, a draconian law which had been introduced to restrain rather than encourage flow of information and opinions. I had moved to Dhaka in 1965. Since I had worked as an editor at the Oxford University Press, and was a political non-entity, my name was given as editor in the application form. Rehman was to be executive editor and Kamal the publisher. Not much came of this application, and each one of us went about our other involvements. Towards the end of 1968, the democratic upsurge in both East and West Pakistan exploded, and eventually destroyed the authority of the Ayub regime. By March 1969, after the failure of the Rawalpindi Round Table talks, Ayub Khan had been replaced by General Yahya Khan, who declared martial law and announced elections in 1970, under the military dictated Legal Framework Ordinance. In this transformed political climate, almost two years after our application, the Information Department informed us in a terse memo that we had been granted a declaration, that we were required to publish Forum regularly every week and that the first issue had to be out no later than November 28, 1969, or else the declaration would be cancelled. Several other prescriptions warned us of our limits. We hurriedly got a team together. Sangbad allowed us to use its printing press. At Shilpacharjyo Zainul Abedin's recommendation, we invited Rafiqun Nabi to sketch our covers. We prepared a long list of regular correspondents in East Pakistan and possible writers in India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. There was no dearth of subjects, what with rising political protests against military rule, and resurgent voices speaking out for democracy and autonomy. Forum covered student demos, Bhashani's peasant conference at Santosh, and emergence of political agendas that moved from six-point autonomy formula to include an eleven-point agenda for social and economic change. Muyeedul Hasan analysed the fast moving political scene every week; Serajul Hussain Khan, a trade unionist, wrote a series on labour relations; KG Mostafa and then AR Khan wrote in-depth pieces on the history of left politics in East Pakistan. Centre pieces on the economic arguments for and implications of autonomy for East Pakistan featured leading economists such as Professors Nurul Islam, Anisur Rahman, Akhlaqur Rahman, and Wahedul Haq. In 1970, Forum's investigative reports on the cyclone and the national parliamentary elections were very incisive. Executive editor Rehman Sobhan was a prolific contributor, often writing additional columns under different pseudonyms. We could always rely on him when copy was short, but he refused to defer to the editor's red pencil, and would reinsert deleted paragraphs, even when space was short. Some of the most evocative pieces were the literary pages, on emergence of a nationalist literature by Razia Khan Amin as well as Sirajul Islam Chowdhury, and an exclusive interview with Shilpacharjyo Zainul Abedin, accompanied by sketches made during his stay with the Fedayeen in Palestine. He also allowed us to use his famine charcoal sketch for the first cover, and a sketch of the 1970 cyclone for a later cover. Forum came to represent popular political aspirations for a progressive, secular, democratic society in East Pakistan. But the weekly was not inward looking, and it hosted regular columns by journalists such as Mazhar Ali Khan, the inveterate Marxist editor of Lahore's Pakistan Times before it was taken over by Ayub Khan, MB Naqvi, the leading South Asian feminist Kumari Jayawardana, Neville Maxwell of The Times, and even a piece by Amartya Sen on bank nationalization in India. Many of these writers were old friends who had a serious commitment to social change. But running Forum was not easy going. We had financial problems since we started with little capital, and received few advertisements, as businessmen saw no advantage in spending money on a journal with low circulation and which was out of sync with their rising ambitions. Optimistically, we had invited life subscriptions. And, at the launch of Forum's first issue, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman became our first life subscriber with a payment of Tk 1,000. But not many others followed. We never did manage to pay our printer's final bill, nor indeed could we recover all our dues from the advertising agency. But that was the least of our worries. Our writings were constantly bringing us to the notice of the military censor, and at least twice we were called in by the martial law authorities. The head of intelligence, Brigadier Jilani, reprimanded us for printing a piece by Mazhar Ali Khan that questioned the millennial celebrations of the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran, when the coup that installed the Shah as king was only several decades old. A second visit was brought about by a write-up on martial law. Once Kamal, as publisher, was called in for an explanation, and the second time I was summoned, as editor, with a warning that we should not write anything to threaten Pakistan's friendly relations with Iran. The logistical problem of getting the weekly out punctually every Saturday was a trial, given that our writers were both uncompensated as well as over-committed, but also because we demanded insightful pieces. Pages were composed with metal fonts, and tied together into wooden blocks. They had to be carried frequently by car, but sometimes even by rickshaw, over bumpy roads from the Forum office, located above the garage of our house on Circuit House Road (currently the site of the Press Institute), to the Sangbad printing press in Bangshal. We accompanied the compositor and the boxes, and checked each page proof. Once, when the transport jerked on the road, the string around the page block became loose and had to be recomposed. We were all shocked the next day when we found a paragraph on political economy meshed into a satirical piece on military strategy by Mumtaz Iqbal, who had become Forum's well informed private eye into military goings on. We had, of course, questioned the logic of printing a weekly in English, but the language was our comparative advantage. We also felt that there was a need to reach the wider audience outside East Pakistan. Indeed, <>Forum<> must have made an impact because even thirty years later some of its readers wonder why we did not continue publication after independence. Many of the position statements made in Forum have stood the test of time and can indeed find an echo today. At the time, elections and representation were equated with democracy. Thirty years later democracy remains elusive. We have realized that it means more than a simple arithmetic of votes. Even as we try to find ways out of the prevailing political autocracy, we are more aware of complex social and political struggles. It is to be hoped that the new Forum will engage with the diverse progressive movements for human rights, democracy, and social justice at all levels of society. Dr Hameeda Hossain is a member of the Editorial Board, Forum Magazine. |