Inside

|

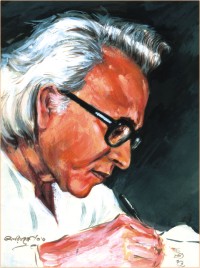

Shamsur Rahman, in retrospect Kaiser Haq re-examines the poetic titan of modern Bangladesh and finds influences and echoes far beyond his much remarked debt to the early 20th century modernists

Still, all this is really quite benign. In shocking contrast is the sinister mind-set exposed in the "Diary from Chittagong" in the Star Weekend Magazine of September 15. The English teacher in a school forbade students to pray for Shamsur Rahman "because he was a communist and an 'infidel' who will have a place in hell." Clearly the mindless monomaniacs who had made an attempt on his life have succeeded in spreading their malign influence in unexpected directions. Exorcising it is no simple matter, and will involve us in a long-drawn struggle. This essay has a more modest aim; to look at some of the major peaks of the long poetic career of Shamsur Rahman, the most productive that this country has seen to date. In a note on himself soon after he received "the first-ever Saarc Literary Award for Lifetime Achievement" in 2001, he acknowledged "about 60-65 books of poems, three books of literary essays, one memoir for young readers, four books of rhymes and five novels and short story collections." The indeterminacy of "60-65 books of poems" is, of course, quite extraordinary; I have also heard him say that he didn't have copies of all his books. Still, the main line of his poetic development can be readily discerned from his hefty Sreshtha Kobita (The Best Poems of Shamsur Rahman). It has long been taken as axiomatic that Shamsur Rahman is the poetic offspring of Jibanananda Das. I echoed the view in my 1985 introduction to his Selected Poems by declaring categorically that: "Rahman was conspicuous in his affinities with Jibanananda when he began writing," and then pointed out that "soon after, he began blending other influences, both Bengali and Western." But lately I have been forced to reconsider the initial formulation in the light of comments made in conversation by Mr Shahed Quaderi (the poet Shaheed Quaderi's elder brother) and Mr Belal Choudhury. Shahed Bhai averred that Jibanananda produces an intense awareness of the quiddity of rural Bengal, something no other modern poet can do. I had to concede the point. Belal Bhai declared that Shamsur Rahman's primary poetic model was Buddhadeb Bose; after browsing once again through both Bose and Rahman, I am inclined to agree. Perhaps it's only fitting that there should be a close kinship in the poetic styles of Bose and Rahman. After all, they have the city of Dhaka in common between them: here Bose spent his formative years, and Rahman was born and spent all his life. In more than one poem Rahman has warmly acknowledged his debt to the older poet, most directly in "Buddhadeb Boser Proti" ("For Buddhadeb Bose"): "My debt to you/ Like a birthmark will never, ever, be erased." In "Beauty Boarding" one verse paragraph provides a graphic acknowledgement of the role of Bose and Kabita, a magazine he edited, in Dhaka's poetic milieu in the 1950s and 1960s: When on certain days Rahman and a few of his younger contemporaries, like Al Mahmud and Shaheed Quaderi, were published in Kabita, thus establishing a vital link between the literary metropolises of the two Bengals. The role of this journal in promoting and shaping new talents ought to make an interesting research topic. In yet another poem, "Buddhadeber Chithi" ("Buddhadeb's Letter") we are beguiled by a rather surreal narrative in which the older poet is described as "a celebrated old lover" of Dhaka city. He is "a consummate craftsman in verse" and is "peerless in prose." He looks upon Rahman's persona, a young man from Kayettuli, just as "an affectionate father looks upon his son," and entrusts him with a letter with an address in Dhaka. The young man cannot locate the address; there's only a field where it ought to have been. When he takes another look at the envelope to confirm the address, he finds it gone. But henceforth; year after year, he visits the address without a location in order to deliver that letter which no longer bears an address. One only has to remember that Buddhadeb Bose's old house in Dhaka's Purana Paltan has become a vanished address to make sense of this mysterious ending. We have here a fine parable of the connection between the two poets, as seen through the eyes of the younger poet. Reading Bose and Rahman side by side one can readily appreciate their kinship in diction, rhythm, and tone, in a sensibility composed with a blend of aestheticism and modernism. Shamsur Rahman, like many others in this country and worldwide, struck a new note in the late sixties, when varied political pressures elicited a strident populism in verse. Among the global exemplars of this mode of versifying were the Beat poets, the Pop poets like the Merseyside trio Brian Patten, Roger McGough, Adrian Henri, and leftist poets like Christopher Logue and Adrian Mitchell. Rahman's populist political poems tend to get widely talked about in public discussions, and are probably his best known works today. Throughout his career Rahman wrote copiously about love and death, with the latter theme, understandably enough, becoming increasingly conspicuous with the passing years. Here's my translation of one of the more engaging death-haunted poems: Before the Journey In an obituary published in the Kolkata periodical Desh, the poet Joy Goswami ends his appreciation of Rahman by saying that it will be interesting to see how future generations respond to his poetry. I am pretty sure that his position as one of the most significant poets to appear after the major modernists of the early twentieth century (Jibanananda et al) will not change. Kaiser Haq is Professor of English at Dhaka University. He has published four collections of poetry and a number of other works. |

S

S