Inside

|

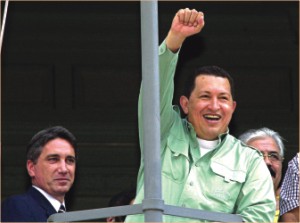

Pirates of the Caribbean In this extract from his new book, Tariq Ali shines a spot-light on Hugo Chavez, new hero of the anti-Bush left in Latin America

The appointment of a new board of directors was the signal for the oil workers union (closely attached to the defeated Accion Democratica apparatus) to go on strike. The politicians, and their friends in Washington and Madrid, were convinced that without the flow of oil the economy would collapse, leading to mass unrest and permitting the use of time-honoured methods to remove a weakened Chavez government. Exactly a year before they invaded Iraq, the United States green-lighted the coup in Venezuela, where the elected president, Hugo Chavez, was regarded as being disloyal to US interests in the region. Venezuela is also the largest oil-producer in South America. The oligarchs were openly thrilled. A former president of the Chamber of Commerce, dilapidated even by Venezuelan standards, was dressed up for the job. A few tame generals then ordered the arrest of Hugo Chavez and he was taken to a military base. So far, so bad. As the news spread, anger grew in the barrios that surround the city and the poor decided to march to the Miraflores Palace. Simultaneously, another event, equally important, was taking place in the palace. With the Western media ready and waiting to introduce the bent president to the world as the saviour of Venezuelan democracy (the New York Times had defended the coup for enhancing democracy), a general came out of the palace and spoke to the military band. He informed them that a new president was about to come out and they should play the national anthem as per usual. The soldiers questioned his orders. Angered by the disobedience, the general turned to the young bugler, an 18-year old soldier, and instructed him to blow the bugle when he saw the new president.

The combination of a popular upsurge and the threat of a soldiers' mutiny saw the triumphal return of Chavez. The people of the barrios had marched down to the city to defend their Bolivarian government. They did so because they knew that Chavez had been removed for helping them, because they understood that a complex gestation had begun in Venezuela, and it was trying to free the country from Washington's domination, and because they believed that even the weaknesses of the Bolivarians were better than the strengths of the Opposition. A year after the failed coup that was certainly my impression from talking to a variety of people from different social backgrounds, some of whom had not even voted for Chavez. The instincts of the young bugler were thus much more in tune with the majority of his fellow-citizens in Venezuela than those of the media folk who had been programmed to respond positively to a blatantly anti-democratic coup, which they proceeded to do without any sense of shame. Within the country itself the two major daily newspapers had no sympathy whatsoever for Chavez (one of them was used to being bribed or clandestinely subsidized by previous governments and had offered the same terms to the Bolivarians but had been refused). It was the Spanish-language CNN, and, in a much more open way, Gustavo Cisneros's channels which backed the coup. The Latin American billionaire, a mix of Murdoch and Berlusconi, was centrally involved in the coup. In Cisneros the Venezuelan oligarchy found its purest representative. Like his equivalents elsewhere, he thought first of his own interests. He served the old political parties only because they served his needs, and he showed his appreciation by using the odd finance minister as a personal bagman. He liked to half-pretend that all this was not for personal gain but for his continent's good. But why should he devote his energies to his continent unless there was money to be made. He had owned Venevision, the largest private channel in Venezuela, since 1961, long before the world had moved in his direction. And now it could be used as a weapon against the barbarians who threatened the power of money. In recent years Venevision became well known for its endless attacks on the Bolivarians as "mobs" and "monkeys," the latter term reflecting the traditional creole attitude to their dark-skinned cousins. How they chuckled in the leafy suburbs at this display of wit.

There was a time when Fuentes would have used his pen against any attempt to negate and vilify all politics that did not conform to Washington's needs. The age of disinformation requires conformity on every level, but for a writer of Fuentes' calibre to permit himself to be used in this fashion is a bit sad. However primitive and simplistic the needs of the system, the global media barons are experts at delivering whatever is required, including coup d'etats and scabby, deformed replacements for elected presidents. This is an extract from Tariq Ali's new book, Pirates of the Caribbean: Axis of Hope, published by Verso, October 2006.

|

I

I "Excuse me, General, but which president do you speak of? We know of only one. Hugo Chavez." The furious general told the bugler to obey orders. At this point, the bugler handed his instrument to the general and said: "You seem to be very keen on playing the bugle. Here it is. You play it." This was a soldier who can proudly tell his children: "I did not obey orders."

"Excuse me, General, but which president do you speak of? We know of only one. Hugo Chavez." The furious general told the bugler to obey orders. At this point, the bugler handed his instrument to the general and said: "You seem to be very keen on playing the bugle. Here it is. You play it." This was a soldier who can proudly tell his children: "I did not obey orders." In contrast, Fox TV in the US appeared as a model of objectivity. What an achievement. And then to approach an old novelist of the calibre of Carlos Fuentes and persuade him to write a glowing introduction to a hagiography in which the Mexican writer canonizes Cisneros as the voice of modernity engaged in battle against a barbarian caudillo.

In contrast, Fox TV in the US appeared as a model of objectivity. What an achievement. And then to approach an old novelist of the calibre of Carlos Fuentes and persuade him to write a glowing introduction to a hagiography in which the Mexican writer canonizes Cisneros as the voice of modernity engaged in battle against a barbarian caudillo.