Inside

|

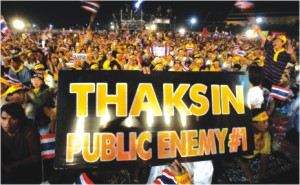

Thailand's silk revolution Reporting from Bangkok six weeks after the army take-over, Larry Jagan examines how it has affected every-day life and takes the temperature of the person in the street Thailand's fledgling democracy was dealt a severe blow when the army moved dramatically to end the country's political crisis. On September 29, the caretaker prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra was removed in a bloodless coup led by the army chief General Sonthi Boonyaratklin, ending months of political deadlock between Thaksin and thousands of pro-democracy demonstrators who had periodically taken to the streets of the capital city demanding that he resign.

The army also took over the country's radio and television stations, cancelling all transmissions and forcing them to play sombre military music and show pictures of the king. This was the first sign that Thailand was going through another dramatic political episode, another coup -- the seventh in the last forty years. International broadcasters, including the BBC and CNN, had their transmissions blacked-out. General Sonthi sacked the prime minister, dismissed parliament, suspended the constitution, and declared martial law. He had removed the prime minister to prevent the country from disintegrating, he told the nation in a televised broadcast later. Since then a civilian government has been formed under a new prime minister, Surayud Chulanont, a former general and army chief. "Our future will be better and power will be returned to the people," General Surayud promised the nation in his first press conference as the new PM. A cabinet of over thirty ministers has also been appointed, most of them businessmen or former government bureaucrats. "They are all mundane choices who bring little to the table; they are unlikely to inspire public confidence in this transitional authority in the way the interim government appointed in 1992 did after the last coup leaders were forced to stand down," says Thai political scientist Giles Ungpakorn of Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. A national assembly of over two hundred representatives has been appointed and a team of experts are drawing up a new constitution. Initially the junta promised to have this in place and hold fresh elections within nine months -- now they are hinting strongly that it may take longer, even up to eighteen months. "I still have no idea how long I will administer the nation, but I will keep it as short as possible," Generals Surayud recently told journalists. So far the coup has been a popular move. Most people in the capital Bangkok, at least, are grateful that the country's political deadlock -- between the elected prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra and the opposition reinforced by a growing extra-parliamentary opposition in the streets -- has been resolved, albeit by non-democratic means. "Thaksin was threatening the country's tranquillity and peace, so he had to be removed, and it could only be done by force," says Dr Sirivudh, an American-trained dentist at one of Bangkok's leading private hospital. A week before the coup, she was an ardent Thaksin supporter. Not a shot was fired during the operation. "It was a peculiarly Thai affair -- a silk revolution," a source close to the army said on condition of anonymity. Analysts believe that the move was orchestrated by senior officials close to the palace. "The army generals would not have moved so decisively if they did not think they had the approval of the king," former senator Kraisak Choonihaven told Forum. But many political analysts believe it is unlikely that the king actually personally sanctioned the coup. He has remained above the country's political quarrelling and repeatedly insisted that Thailand's political stalemate had to be resolved constitutionally. "We have seized power because the caretaker prime minister has caused an unprecedented rift in society, widespread corruption and nepotism, and interfered with the country's independent agencies, crippling them so that they could not longer function properly," General Sonthi said in his televised address to the nation a day after the coup. In the days immediately after the coup Bangkok remained calm, with few visible signs of the momentous events of September 19. But two months after the coup small groups of soldiers still patrol the city to ensure that there is no break-down of law and order. The mood on the streets of Bangkok remains subdued while the implications of General Sonthi's coup are still quietly discussed, even by the city's street stall sellers. Thaksin remains popular with the poor who feel that he has tried to improve their lot with a 30 baht (less than a dollar) health scheme, the injection of funds into the rural villages, and the suspension of farmer's debt. But even they are reluctant to continue to champion him in the face of General Sonthi's move. "Perhaps he had gone too far and was starting to be a threat to the country's stability," says Rung, a young single mother who was full of praise for Thaksin because of his health scheme.

"I never support coups, but this one was almost inevitable," says former senator Kraisak, whose father Chatichai Choonavan was toppled as prime minister in Thailand's last coup in 1991. "It's one step back to allow two steps forward," he mused. Many of the students at the country's prestigious Chulalongkorn University were of the same mind. "It may have been an authoritarian, unconstitutional, and undemocratic move, but Thailand will emerge stronger out of this and its democratic institutions will be strengthened in the long-run," opines an economics student. Almost all Thais hope that this coup will be unlike any other coup in a country that has already gone through 17 of them. "This coup will be different to all previous coups as something good will emerge from it," says a political science student. But there are those, who also opposed Thaksin, who understand that a coup cannot be good for democracy. "There is no such thing as a good coup," says leading member of the Democrat Party and former foreign minister, Surin Pitsuwan. "The coup is a disaster for Thai democracy, it is a return to the bad old days of military rule," says academic Giles Ungpakorn. "Thaksin should have been defeated by democratic means -- it would have taken longer but it would have been a better alternative to military force." "The coup is not good, it is not bad," Khun King, a domestic worker, told me a day after the coup. "Thankfully, though, no one was killed," she added. For many that is probably the most important aspect of this coup -- attitudes would have been more polarized if Thaksin's supporters in the army and especially in the police force, where he also once served as a colonel, had resisted. Only a few academics are prepared to voice their concerns over the military take-over. Some fear it has set a bad precedent for the future of the country's democracy, though there are those who argue it was a necessary evil and the public now has to closely monitor the junta and help guide the country back to full democratic. "The people's sector must get involved, or it will turn out that we just gave the military a blank cheque," says Surichai Wun-Gaeo, a political scientist at Chulalongkorn University and a member of the new National Legislative Assembly. If the debate around the morality of the coup is subdued, the circumstances around this particular coup are certainly exceptional. Although the army chief moved against the democratically elected government, it was on the basis that Thaksin Shinawatra had become a dictator and was ruining the country through encouraging and promoting rampant corruption. For many, Thailand's constitution, drafted and promulgated in 1997, was a beacon for democracy, not only in Thailand but South East Asia as a whole. The problem was that no constitution is strong enough to regulate a government that has overwhelming popular support through the ballot-box but is nonetheless as tyrannical as any unelected military or authoritarian regime.

Prime Minister Thaksin had interpreted the political movement against him as a threat to democracy. "Key democratic institutions, such as elections and the observance of constitutional limitations on government, have been repeatedly undermined," he wrote to US president George Bush several months ago, explaining Thailand's political problems. His critics of course argued that over the last five years since his original electoral landslide victory, Mr Thaksin had usurped democracy and the constitution, and left those who opposed him with no alternative but to take to the streets to vent their feelings and protect the constitution. "It is not true that Thaksin represents genuine democracy and overthrowing him in the street is unacceptable," says a senior political scientist at Chulalongkorn University, Dr Titinan Pongsudhirak: "Just because you have someone coming along and winning elections is not tantamount to having democratic rule." Thaksin had used his two major election victories -- in 2001 and again in 2005 -- as his rationale for ruling without regard to the opposition and for sweeping aside any criticism. "He has become a populist dictator, using the 19 million votes he got as justification for his absolute rule," Dr Titinan told Forum before the coup. "He is far more authoritarian than any previous military dictatorship before him." Most of Thailand's academics and intellectuals have insisted in recent months that although undeniably popular with segments of the Thai electorate, Thaksin posed a major threat to the country's democratic system. "Thaksin says he plays by the rules, but he is the one who broke the rules most of the time," says Kavi Chongkittavorn, a senior editor with the English language daily newspaper the Nation: "I think democracy means a lot of things -- not just votes. It means checks and balances, it means transparency, it means how you use powers, it means you are accountable as a leader." Now the army chief has ended the debate decisively and removed Thaksin. Whether this military coup will now help strengthen Thailand's democratic institutions remains an open question. There are already signs of restlessness amongst a section of the country's university students. They have begun to organize demonstrations against the junta. So far these have been restricted to the university campuses, but these are likely to grow -- as they did after the last coup. The longer the military-installed regime procrastinates and does not provide decisive leadership, the more the street demonstrations are likely to grow. At present, martial law prohibits demonstrations and political meetings, but the new prime minister has promised to rescind this in the new year. What is certain is that Thailand's economic development and stability now depend on a speedy return to democratic and civilian rule. Opposition to the junta will grow if there is any continued dip in investor confidence and business growth. Consumer sales have fallen dramatically in the last seven months because of the lack of consumer confidence. Thailand's important tourist and entertainment industries are also feeling the pinch. "We only have a fraction of the customers we had this time last year," the manager of a bar in Nana, one of Bangkok's leading entertainment areas, complained to me recently. "If it doesn't pick up soon we will have to lay off staff and even consider closing the bar down," she added. In the end, the junta will be judged on its ability to return Thailand's prosperity, as much as its commitment to return power to the people. The coup has proven that in Thailand, at least, democratic ideas are still under-developed, and public opinion is more concerned with its pocket than with lofty ideals. Larry Jagan is a former Current Affairs Editor, Asia, BBC World Service. |

The army moved swiftly and effectively to take control of the country while the premier was abroad attending the UN general assembly in New York. Several battalions of soldiers stationed around Bangkok and loyal to the army chief were quickly mobilized and moved into key positions around the city late at night. Tanks and heavily armed soldiers took up positions at strategic points in the city, including government house, the parliament building, and the palace.

The army moved swiftly and effectively to take control of the country while the premier was abroad attending the UN general assembly in New York. Several battalions of soldiers stationed around Bangkok and loyal to the army chief were quickly mobilized and moved into key positions around the city late at night. Tanks and heavily armed soldiers took up positions at strategic points in the city, including government house, the parliament building, and the palace. Many of the rank-and-file opponents of Thaksin were clearly jubilant with the new political twist. "It's very exciting, someone had to do something to end this impasse," a computer science student from Chulalongkorn University told me. "General Sonthi has done the right thing."

Many of the rank-and-file opponents of Thaksin were clearly jubilant with the new political twist. "It's very exciting, someone had to do something to end this impasse," a computer science student from Chulalongkorn University told me. "General Sonthi has done the right thing." The political turmoil which engulfed Thailand since the beginning of this year was fundamentally about the meaning and spirit of democracy -- though often tempered by the vested interests of some of the leading protagonists.

The political turmoil which engulfed Thailand since the beginning of this year was fundamentally about the meaning and spirit of democracy -- though often tempered by the vested interests of some of the leading protagonists.