Inside

|

Evolution of Bush Doctrine In this extract from his new book, Martin Woollacott traces the mistaken thinking of the Bush administration that has led to the current crisis in Iraq The British Labour politician Richard Crossman, who was for a time a supporter of both Ben Gurion's Israel and of Gamal Abdel Nasser's Egypt, came, soon after the Suez War, to believe that the Arab world should be left to stew in its own undemocratic juices. In lectures he gave at the Weizmann Institute in Israel in 1959, he told his audience that the West ought to apply to the Middle East a version of President Roosevelt's "good neighbour" policy toward Latin America.

Crossman intended himself to be understood as no longer having any active interest in Arab democracy, because it was now beyond the ability of Britain and other Western countries to spread democratic values. But he also implied a readiness to intervene, even though he had previously been "a voice in the wilderness, preaching that we should withdraw from the Middle East as totally and completely as we had withdrawn from the Indian sub-continent.” A few years later, Miles Copeland, involved in American back door diplomacy and intelligence work in the Middle East, came to a similar conclusion: "We will henceforth look at the politics of a backward country the way a doctor looks at a diseased patient: with concern but without involvement. A segment of the human race, to wit ourselves, intends to put a man on the moon, to cure cancer and the common cold, and to solve all the problems that overpopulation and waning raw materials are going to present us with. Anyone else who wishes can join in -- regardless of race, religion, or color. But anyone who is more concerned with such pursuits as burning down foreign embassies, 'rejecting Western imperialism' and all else, to acquire 'freedom from imperialism' can have it with our blessing." Crossman's and Copeland's views, in essence, constituted the underlying principle of Western policy toward the Middle East for decades to come. Threats would be dealt with, and interests defended, but Western countries only intermittently saw any duty, or need, to advance the cause of democracy as an end in itself. Indeed, they would positively discourage democracy, or ignore human rights issues, if to do otherwise would damage their interests. Kennedy's and Carter's urging of reforms on the Shah of Iran were notable exceptions. The contrast with George W Bush in 2003 is striking. "Sixty years of Western nations excusing and accommodating the lack of freedom in the Middle East," he said in November that year "did nothing to make us safe. As long as the Middle East remains a place where freedom does not flourish, it will remain a place of stagnation, resentment and violence ready for export. And with the spread of weapons that can bring catastrophic harm to our country and to our friends, it would be reckless to accept the status quo. Therefore, the United States has adopted a new policy, a forward strategy of freedom in the Middle East."

But freedom and threat were now brought dramatically under the same roof by the president. Without freedom, there would always be a threat. With freedom, threats simply could not arise. The moral issues here are tangled. The Western neglect of democracy and human rights in the Middle East, and elsewhere, which characterized much of the last 50 years, has been widely condemned. In practice Britain, France, and the United States, with Israel joining in on occasion, supported unrepresentative regimes because they were useful. Where they opposed unrepresentative regimes, they did so out of interest, not principle. "Historically," writes the journalist and author Said K Aburish "legitimate nationalist regimes were rejected when they were considered a threat to Western interests while friendly illegitimate ones were supported regardless.” Against this background, the Bush administration's elevation of democratic values and human rights may seem admirable in theory, but also arrogant. It implies both that the United States can, almost by fiat, cause democracy to come into being, and that this will be a democracy which will always produce decisions favourable to America. The one suggests too much ambition, and the other an Orwellian equation -- states will freely choose what Washington wants and by doing so will prove that they are free. Americans had always tended toward the idea of a more complete transformation of the non-Western, and indeed of the non-American world, than their British and French predecessors. Neo-conservatives, taking this to its logical conclusion, envisage a change so fundamental that a majority of the population of the Middle East will actively and "naturally" support Western ways, values, and interests. This would go beyond the many existing affinities, sympathies, and connections which tie together Western and Middle Eastern countries. In particular, it would reverse the turn toward Islamist politics, especially in their violent form, and encourage not just tolerance of Israel but a friendly acceptance. There were deep divisions about nation building and military occupation among the architects of the 2003 war in Iraq. But the prevailing view was that underneath the carapace of the regime, Iraqi society had in effect been preparing itself for democracy. This view rested on the assumption that simply because bad governments had opponents and victims, their opposition would, by definition, be democratic. It exaggerated the strength of that part of the Iraqi opposition which was genuinely democratic. In a further irony, the way in which military intervention was managed ended up by weakening, and exposing to victimization, the very segments of Iraqi society -- middle class, educated, and relatively secular -- most ready for democratic change. If, in the end, this class does prevail, or at least retains influence, it cannot be said that the path has been made easy for them. The intertwined moral and practical problems raised by the second American war against Saddam were many. The legal justification for going to war was implausible, but, against this, the invasion of Iraq would also have a liberating purpose. Many Iraqi exiles, who had no time for the United States and did not understand why Washington was suddenly so bent on attacking Saddam, were nevertheless happy at the prospect. For them, it was enough that America was planning to do something they desperately wanted to see done. Second, the al-Qaeda attacks had jolted the United States out of the indecisive and non-committal mood of the nineties. Support for the operation might induce America, even under its unpromising government, to look again at other aspects of its policies, including its attitude toward international agreements and institutions, and, in the Middle East, toward Israel.

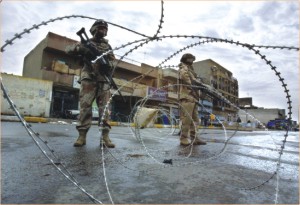

Rescuing Iraqis from oppression had always been part of the Bush administration's rationale for the war, but it grew in importance as the WMD case collapsed in the months after the invasion. It was then further inflated into a region-wide campaign for democracy which went beyond the original hope, or assertion, that a democratic Iraq would influence its neighbours. Everywhere in the Middle East, now, it was claimed, the United States would actively seek democratic change in both friendly and unfriendly states. Democracy, as the Americans conceived it, might well be a good in itself. Yet it was clear that the pursuit of democracy, whatever was thought about its chances for success in Iraq, or elsewhere, was one face of an attempt by the United States to reassert its strategic control of the region. The Bush administration saw itself involved in a process of bringing states which had been hostile to America into a larger and larger family of societies sharing essentially American values and obeying prudent rules of behaviour set by the powerful, above all by the United States itself. To it fell the task, it seemed to the administration, of dealing with the hold-outs and rebels, of whom Saddam was a prime example. The Middle East, whose states, except for Turkey, have not been able to achieve the degree of autonomy which other non-Western societies, like China, Japan, and India, have managed to do, is a region whose peoples are resistant to outside interference precisely because they have endured so much of it. The assumed Western right to control the Middle East, forcefully or otherwise, is at the centre of the argument. The contradiction, between wanting control and respecting the rights of the states and peoples of the region, could be solved on paper by emphasizing the importance of democracy. This would, supposedly, bring to power governments with which there could be no major disagreements. But in practice the problems were far more complex than a simple opposition between bad governments and democratic ones, or a simple equation between democratic governments and pro-Western ones, would suggest. Books cited: A Nation Reborn. Richard Crossman. Hamish Hamilton, London, 1960; The Game of Nations. Miles Copeland. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1969; A Brutal Friendship. Said K Aburish. Indigo, London, 1998. Martin Woollacott is a former Foreign Editor, The Guardian. This column draws on his book, After Suez, published by IB Tauris, October 2006. |

This was that the local states "should be permitted to be corrupt, to suffer under dictatorships or to develop democracies, provided only that they did not constitute a threat to their northern neighbour. Whether we like it or not, the Arab states, since the Suez venture, have achieved the same kind of independence."

This was that the local states "should be permitted to be corrupt, to suffer under dictatorships or to develop democracies, provided only that they did not constitute a threat to their northern neighbour. Whether we like it or not, the Arab states, since the Suez venture, have achieved the same kind of independence." Bush's democratic "new start" had, in fact, been preceded by a period of some years in which the policies of both the United States and the European Union placed increasing emphasis on efforts to encourage democracy in the Middle East.

Bush's democratic "new start" had, in fact, been preceded by a period of some years in which the policies of both the United States and the European Union placed increasing emphasis on efforts to encourage democracy in the Middle East. Third, while the idea that the Middle East was ripe for democracy was simplistic, it was clear that the peoples of the region were unhappy with the governments they had, and were not inclined to welcome the uncompromising and angry form of Islam represented by bin Laden.

Third, while the idea that the Middle East was ripe for democracy was simplistic, it was clear that the peoples of the region were unhappy with the governments they had, and were not inclined to welcome the uncompromising and angry form of Islam represented by bin Laden.