|

Cover

Story

Reading

in

Translation

A Journey

Through History

Mustafa

Zaman

When

does the essence get lost in translation? When does a translation

fail to whip up the same enthusiasm as does an original? These

key questions may jostle the mind of every disenchanted reader.

The answers lie only in the fact that like an original, any

translation too, either simply works or does not. When

does the essence get lost in translation? When does a translation

fail to whip up the same enthusiasm as does an original? These

key questions may jostle the mind of every disenchanted reader.

The answers lie only in the fact that like an original, any

translation too, either simply works or does not.

There is no easy solution to the problem of rewriting a novel,

a poem or an epic, or even scientific work in another language.

As with the original, the translation too needs a talented

writer to make the pen cough up the information, the wisdom,

the turn of events and the artistic energy almost in the vein

of the original. However, as many of the translations fail

to emulate the essence, there are works that even supersede

the original. Gabriel Garcia Marquez once said about the English

translation of his masterpiece, "One Hundred Years of

Solitude", of having far more lucid a language than what

he wrote in Spanish.

The history of Bangla language too is replete with examples

of translations that in essence stand on their own as they

often surpass the feat of the original work. But, there is

a whole gamut of literary exploitation that simply fails to

bring the real brew to the people of this riverine flatland.

In the context of the history of the Bangla Language SWM tries

to measure the volume and value of works that sprang from

other languages.

The

history of Bangla literature is capacious. It has been the

ground that was tilled in many different ways at various points

of time to make many different harvests. "It was the

military feudalism during the rule of Allauddin Hussain Shah

(1494-1590) that Mahabharata and Ramayana

were first translated in Bangla. The state language was Farsi

(Parsian), and Sanskrit was the language of the Hindu pundits;

it was in this backdrop that the Hindu epics were first translated

in the popular language that was Bangla," points out

Salimullah Khan, a linguist with a strong penchant for historicity,

one who is also a writer who translated a number of philosophical

works. He pin points the rise of Chaitanya Dev, the Vaishnav

avatar, as being the Renaissance of Bengal. The

history of Bangla literature is capacious. It has been the

ground that was tilled in many different ways at various points

of time to make many different harvests. "It was the

military feudalism during the rule of Allauddin Hussain Shah

(1494-1590) that Mahabharata and Ramayana

were first translated in Bangla. The state language was Farsi

(Parsian), and Sanskrit was the language of the Hindu pundits;

it was in this backdrop that the Hindu epics were first translated

in the popular language that was Bangla," points out

Salimullah Khan, a linguist with a strong penchant for historicity,

one who is also a writer who translated a number of philosophical

works. He pin points the rise of Chaitanya Dev, the Vaishnav

avatar, as being the Renaissance of Bengal.

"Sixteenth

century is the time of Chaitanya Dev, and it is the beginning

of Modernism in Bengal. The concept of 'humanity' that came

into fruition is contemporaneous with that of Europe,"

notes Khan. He believes that all hopes of progressing on that

humanistic line were dashed when the British came and forced

all things Bangla into a "subordinate position".

Back in

the 16th century, the Vaishnav movement led by Chaitanya had

various social, political and literary implications. Most

importantly Vaishnavism forced to bring the language of the

masses to the fore. "The discourse of knowledge was Sanskrit

at that time. It was Chaitanya who emerged from Sylhet and

settled in Orissa to spread his humanistic ideas that spurred

a process of interaction between the elite and the subaltern,"

Khan points out.

Chaitanya

led a revolt against the Sanskrit-speaking pundits of his

time. The Sri Krishna Kirttan, a series of story-telling lyric

poems, is a major work in Bangla of his time. "It is

the tale of Uttar Pradesh retold in Bangla," says Khan.

"The Radha-Krishna tale of north Indian origin assumed

Bangali characteristics in Sri Krishna Kirttan," continues

Khan. He terms the Bengal Vaishnavism that contributed in

bringing Bangla into use by superseding Sanskrit in the "phase

one" of the history of Bangla literature.

Khan is

unequivocal about the fact that "the history of Bangla

literature is the history of translation". It was in

the first phase that Mahabharata and Ramayana

were translated, the former by poets like Kavindra Parameshavra

and Shrikara Nandi, two major poets during the rule of Hussain

Shah. It was also the era when through the Bangali brand of

Vaishnavism the poems of Radha-Krishna was adapted into Bangla.

The second

phase of the history of Bangla too is a time when a lot got

translated. New poets emerged, who are now popularly known

as "medieval poets", were the major exponents of

the Arakan court. Alaol (1607-1680), Daulat Kazi (1600-1638),

Muhammad Khan, Daulat Ujir Bahram Khan and the likes steered

Bangla literature on a relatively newer course. Outside the

Arakan court there was Shah Abdul Hakim.

Alaol's

most celebrated work titled Padmavati was based on the Hindi

original named Padmavat by Malik Mohammed Joyasi. Even his

major works like Saptapaykar and Sikandernama were of (Farsi)

Persian origin. Heavily influenced by his two predecessors

Kanshi Ram Das and Krittee bash, Alaol was the most prolific

poet of 17th century Bengal. Both Kanshi Das and Kritti bash

had translated the Ramayana in the previous era. Alaol's

most celebrated work titled Padmavati was based on the Hindi

original named Padmavat by Malik Mohammed Joyasi. Even his

major works like Saptapaykar and Sikandernama were of (Farsi)

Persian origin. Heavily influenced by his two predecessors

Kanshi Ram Das and Krittee bash, Alaol was the most prolific

poet of 17th century Bengal. Both Kanshi Das and Kritti bash

had translated the Ramayana in the previous era.

Daulat

Kazi based his major work on Ramayana and Mahabharata, the

epics by Jaydev and Kalidas. A Sufi by faith, he espoused

a liberal view. His work, like many other poets of his time,

doted on all kinds of literary sources, be they Hindu, Vaishnav

or Islamic in origin. Baharam Khan's Laily Majnu and Imam

Bijoy were also translated from original Arabic literature.

The former work got eternally tied up with the folklore of

Bengal.

"It

was the time when a new set of writers started translating

from Awadhi, the language of Lukhnow, which was the classical

Hindu land of Ayodhya. Awadhi itself was an amalgam of Hindi,

Urdu and Farsi. Most of the translations of this period are

from Hindi and Farsi," Khan says.

“Numerous

works were translated from Arabic to Bangla in the second

phase. And the third phase saw a flurry of translations from

English to Bangla," says Khan, who also points out that

it was in the 19th century, 70 years after the conquest of

India by the East India Company in the 1760 that "the

creative spurt first became visible".

"It

was in 1830 onwards that two kinds of forces came into play

-- one of secular enlightenment and the other of missionary

aspirations," Khan adds. "Thousands of books were

translated into Bangla for the first time in history. There

were books on geography, medicine and other science subjects.

And the missionaries translated a lot of religious texts,"

he reveals.

According

to Khan, the great hey-day of translation ended in 1857 when

Kolkata University came into existence and English was imposed

as the medium of learning. "The time between 1820 and

1860 was the most fertile. It was the time of Rammohon. Thousands

of books that were translated then are now lost forever,"

says Khan. He pins down the fact that the School Text Book

Society and the School Society that were established in 1820,

had opened up the floodgate for learners in Bangla. "The

periodical like Tottobodhini (1840s) and Bibidartho Shogroho

(1850s) regularly printed scientific texts in translation,"

Khan testifies. Radhanath Sikder, who surveyed the height

of the Himalayas, used to translate scientific discourses

for the latter journal. It was McCall's policy of education

that made English the only medium of learning, putting an

end to the need for works in translation. According

to Khan, the great hey-day of translation ended in 1857 when

Kolkata University came into existence and English was imposed

as the medium of learning. "The time between 1820 and

1860 was the most fertile. It was the time of Rammohon. Thousands

of books that were translated then are now lost forever,"

says Khan. He pins down the fact that the School Text Book

Society and the School Society that were established in 1820,

had opened up the floodgate for learners in Bangla. "The

periodical like Tottobodhini (1840s) and Bibidartho Shogroho

(1850s) regularly printed scientific texts in translation,"

Khan testifies. Radhanath Sikder, who surveyed the height

of the Himalayas, used to translate scientific discourses

for the latter journal. It was McCall's policy of education

that made English the only medium of learning, putting an

end to the need for works in translation.

The era

of learning in Bangla was followed by a barren time in the

field of translation. English became the Lingua Franca of

that time, as Sanskrit used to be in the olden times. Like

the Buddhist scholars of the 15th century who shunned the

language of the masses and opted for Tibetan, the intelligentsia

groomed in English too, avoided Bangla altogether. It was

the 19th century, and English as a language ruled Bengal.

"It

was during the political upheaval of the 1930s that Bangla

was again sought by both Muslim League and the Congress leadership

to be able to relate to the masses. The Congress even proposed

to make it the medium of education," says Khan. And he

sees the era of so-called "renaissance of Bengal"

when the intelligentsia absorbed all things English as a "dark

age" while "living on borrowed ideas".

“You

need translations to be on a level with the world, we lagged

behind in this as we were ruled by the British. The translated

works say how much of the ideas of the world is being read

in your own language," observes Khan.

Thousands

of works have been translated into Bangla over the last 600

years. Yet the field of philosophy remains a vacant slot.

"You wouldn't find a dependable edition of Karl Marx

in Bangla. The Moscow-based Progress Publisher put out the

third to the fourth edition, but they are no good," says

Khan.

The

Cold War era is the fourth phase that has seen a spell of

works in translation. As the two superpowers were locked in

a tug of war in the information arena, it soon turned into

a race between "exporting" knowledge to supersede

the "other". The Russians translated and published

on their own by employing people like Noni Bhoumik, Dijen

Sharma, Arun Shome and Hayat Mamud in Moscow and then they

exported the books to the receiving countries to be sold at

very low prices. The

Cold War era is the fourth phase that has seen a spell of

works in translation. As the two superpowers were locked in

a tug of war in the information arena, it soon turned into

a race between "exporting" knowledge to supersede

the "other". The Russians translated and published

on their own by employing people like Noni Bhoumik, Dijen

Sharma, Arun Shome and Hayat Mamud in Moscow and then they

exported the books to the receiving countries to be sold at

very low prices.

"The

Americans had a better policy. They paid a section of Bangali

intellectuals in the 1960s to translate anti-communist literature.

Then they paid the local publishers hefty amounts to print

and distribute the books in the local market," Khan harks

back to the Cold War days. "The Franklin Book Project

in Dhaka was busy doling out money to translate and publish.

Most of these translations were bad. And the books too are

not in demand. The translations done in Moscow were third

rate, with a few exceptions. Somor Sen did some excellent

translations," Khan continues.

The Cold

War did produce a few sparkling moments. Syed Shamsul Haq

translated Saul Bellow's Henderson--The Rain King, and Monir

Chowdhury showed his acumen as a translator of several American

masterpieces.

Moshiul

Alam, a writer and an Assistant Editor of Prothom Alo, says

that several of the later period translations from the Progress

Publisher were good. "Arun Shome who translated Tolstoy's

Crime and Punishment and Resurrection from the originals were

really good," says Alam.

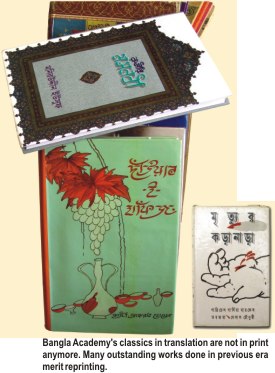

The Bangla

Academy that came into being in 1955, to this day, remains

a hub of the translators. Most of its significant translations

were done in its early days, as it now focuses more on textbooks

to generate income. "Their translations are not enough;

the translators too are paid inadequately. But the programme

they have is invaluable. This is the one that put out El Beruni's

work in translation. No other private publisher could accomplish

this," Khan emphasises.

"There

was a separate translation cell in Bangla Academy in the 1960s.

And they had their own translators; Sardar Fazlul Karim was

one such translator. It was in the 1960s that Nietzche's Thus

Spake Zarathustra, and even Crime and Punishment were published,"

Moshiul Alam reveals.

The Islamic

Academy, founded during the Ayub rule, later became the Islamic

Foundation in the liberated Bangladesh. It contributed to

a lot of translation from Arabic and Farsi. However, even

before the existence of any institution, Bhai Girish Chandra

Sen translated the Quran in the 1880s.

The post-liberation

scenario could have been a time of reawakening to the world

of knowledge, but it was not. "Even Bangla Academy's

efforts fizzled out after liberation. We soon began to see

that it is the willingness on the part of certain individuals

that made translations possible. Nowadays, it is the writer

who takes a fancy to a work of literature and then takes steps

to translate it," Alam observes.

The post-independence

phase has little to crow about. There has been a slide in

translations from the originals. There has been intermittent

flickers of light that are solely the contribution of a handful

of talented writers. "Abu Mohammad Habibullah did some

work in the 70s that are from the original, for example the

Bharat-Totto of El Beruni. Al Mukaddima, Ibne Khaldun was

also translated from the original language by Golam Samdany

Koraishi," observes Zamil bin Siddique, a senior sub-editor

of the Daily Prothom Alo. Zamil also praises the pre-independence

efforts of Monir Chowdhury in translating Shakespeare.

And after

1971, it was Zafar Alam who single-handedly translated the

works of Krishan Chandr, Ismat Chugtai and Prem Chand from

Urdu. Abdus Sattar remained the only exponent of Arabic translation,

he worked on Nagib Mehfuz and Taufique al Hakim.

It was

the theatre movements of the 1970s and the 1980s that spurred

many writers to pick up the pen to translate some major works.

"Syed Haq translated Macbeth and Tempest as well as Julius

Caesar, which was adapted in Bangla and was called Gono Nayok,"

recalls Zamil.

Zamil

also believes that Sheba Prokashoni, with their concise versions

and lucid language, has been able to capture the imagination

of the younger readers. He extols their effort in bringing

out concise versions of Mahabharata and Ramayana. But, Alam

disagrees. According to him, most of what this popular publisher

churned out in the last three or so decades are "efforts

to mimic the story lines of the original works, they seldom

take into account the artistic verve that a good piece of

literature expresses".

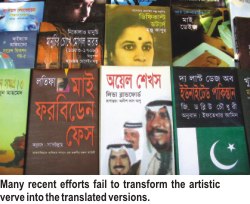

In the

1990s, there has been a steady rise in the number of translation

of books that had fetched international awards. And they lack

all that is essential to call a translation a work of literature.

From Arundhati Roy to Salman Rushdie, most awarded writers

have enjoyed getting translated in Bangla. These works severely

lack artistic merit.

It

is Khaliquzzaman Illias, who wrote Myth-er Shokti from Joseph

Cambel's The Power of Myth, and Gulliver's Travels in Bangla,

upon whom the hope of getting a good translation could be

rested. He also translated Sholokov that came out from Mukta

Dhara, a publishing house that used to concentrate on cheap

production. Roshomon is another of his much-talked about translations. It

is Khaliquzzaman Illias, who wrote Myth-er Shokti from Joseph

Cambel's The Power of Myth, and Gulliver's Travels in Bangla,

upon whom the hope of getting a good translation could be

rested. He also translated Sholokov that came out from Mukta

Dhara, a publishing house that used to concentrate on cheap

production. Roshomon is another of his much-talked about translations.

However,

Illius and a few like Shibobroto Bormon and GH Habib are the

ones who often resort to the English versions of the original

work. Habib translated the much celebrated One Hundred Years'

of Solitude and Italo Calvino's Invisible City and Bormon

did an excellent job with VS Naipaul's Miguel Street, and

Sayed Wahliullah's French writings like How to Cook Beans

and Ugly Asian; they subsequently came out in the special

supplements of Prothom Alo.

Though

good translators are quite a few, there are some who bring

a breath of fresh air to the literary scene as well as the

world of knowledge. One such translator is Salimullah Khan,

who translated Orientalism by Edward Said. Now, one of his

series of Plato's writings from Greek are to hit the market

this month. "It is coming out under the rubric of Plato's

Collected Works containing three Socratic dialogues,"

says the translator. Khan also did the translation of Dorethy

Soelle from the German original back in 1998. As for Plato,

it was Rajani Kanto Guho who first translated four dialogues

from the Greek original; that too was in 1922.

Though

a lot of literary works has seen its publication in Bangla,

philosophy and science remain almost a closed chapter as there

are a few writers capable of translating them. Though Bangla

as a language still lacks a grammar of its own, it has proved

its significance as an incredible vehicle of expression, both

in original writing and in translation. But how the Bangla-speaking

people will shape their future alongside that of the language,

depends a lot on what they are capable of interiorising using

the mother tongue.

World

Literature in Bangla

Shamim

Ahsan

The

history of translating literary works of other languages into

Bangla goes back a long way. In the 19 century, the work of

translating took a new turn. The missionaries in the then

Indian subcontinent believed that they must have a good grip

on Bangla to deepen their roots here and perpetuate the colonial

rule. They were thus very eager to learn Bangla. But the Bangla

that was spoken was poles apart from the Bangla that was used

in literature. Bangla literature at that time basically meant

Bangla poetry. Bangla prose as we know it today was nonexistent.

This endeavour was centred on the Fort William College. A

group of pundits led by Mrittunjoy Torkalanker and Ram Ram

Basu and others were given the responsibility of writing Bangla

prose. It was decided that works of Sanskrit, Persian and

Arabic literature would be translated into Bangla. That was

the time when the colonial rulers had taken up steps to translate

works of other languages into Bangla. The

history of translating literary works of other languages into

Bangla goes back a long way. In the 19 century, the work of

translating took a new turn. The missionaries in the then

Indian subcontinent believed that they must have a good grip

on Bangla to deepen their roots here and perpetuate the colonial

rule. They were thus very eager to learn Bangla. But the Bangla

that was spoken was poles apart from the Bangla that was used

in literature. Bangla literature at that time basically meant

Bangla poetry. Bangla prose as we know it today was nonexistent.

This endeavour was centred on the Fort William College. A

group of pundits led by Mrittunjoy Torkalanker and Ram Ram

Basu and others were given the responsibility of writing Bangla

prose. It was decided that works of Sanskrit, Persian and

Arabic literature would be translated into Bangla. That was

the time when the colonial rulers had taken up steps to translate

works of other languages into Bangla.

Some of

the giant literary figures of the nineteenth century translated

from works of Sanskrit literature. Ishwarchandra Bidyasagar

translated Kalidas' Shakuntala, Rajshekhar Basu translated

Valmiki's Ramayan and Kashiram Das did Byadbesh's Mahabharata.

But as far as translating western literature is concerned

the most significant name is certainly Micheal Modhusudan

Dutta, says litterateur and critic Abdul Mannan Syed. Modhusudan

is the first major Bangali poet who was very well versed in

world literature. He knew fourteen languages including Greek,

French, Italian not to mention Sanskrit and Persian. He translated

from both Homer and Dante.

According

to Syed, another major Bangali poet of the nineteenth century

who has great contribution to Bangla translation literature

is Sattyendranath Dutta, whose mastery over rhyme earned him

the title of "Chander Jadukar" (the magician of

rhyme). According

to Syed, another major Bangali poet of the nineteenth century

who has great contribution to Bangla translation literature

is Sattyendranath Dutta, whose mastery over rhyme earned him

the title of "Chander Jadukar" (the magician of

rhyme).

He had

a three-book series of translated works from literary troves

of such languages as varied as English, French, German, Italian,

and Japanese. "His translation of Baudleaire and Heinrich

Heine's works are great treasures of Bangla literature. He

also translated the Hadith," Syed reveals.

Rabindranath

also did some translations. He admired the English Romantic

poets and translated quite a few poems of Coleridge, Wordsworth,

Shelley, Keats and Byron. He also translated the most influential

English poet of his era (of the first half of the twentieth

century) Eliot's poems. Besides the compendium of English

writers, Tagore has translated Victor Hugo and Hafiz' s works.

Kazi Nazrul

Islam knew Persian very well and his most favourite poet was

Hafiz. His translation of Hafiz and Omar Khaiyam's works are

remarkable. His great authority of Persian and Arabic literature

has inspired him to import many Persian and Arabic words into

his writing, which has greatly enriched Bangla vocabulary.

His hamd and nath displays how a great poet absorbs and makes

foreign words, phraseology and syntax the property of his

own native language.

The

poets of the thirties, particularly Buddhadev Basu, Sudhin

Dutta and Bishnu Dey have had their share of contributions

to Bangla translation literature. Buddhadev Basu's translation

of Baudleaire's poems is considered a milestone in the whole

range of translation literature while Sudhin Dutta, who was

very well-versed in French and German, had translated a good

number of poems from both the languages. The

poets of the thirties, particularly Buddhadev Basu, Sudhin

Dutta and Bishnu Dey have had their share of contributions

to Bangla translation literature. Buddhadev Basu's translation

of Baudleaire's poems is considered a milestone in the whole

range of translation literature while Sudhin Dutta, who was

very well-versed in French and German, had translated a good

number of poems from both the languages.

When

it comes to institutional efforts, Bangla Academy has done

a fairly large volume of translations works. Litterateur and

academicians Professor Kabir Chowdhury who has some 50 books

of translation to his credit, though acknowledges Bangla Academy's

endeavour in this respect, is not exactly full of praise as

far as quality is concerned. The Academy has sponsored translation

of Arabic masterpieces and got quite a sizable volume of works

of Sadi, Rumi and Iqbal translated into Bangla. Chowdhury

believes that quality-wise many of them are rather poorly

done. Especially with poetry, the translators had the right

techniques or skills but often lacked poetic capability, which

often render the translated versions lifeless.

Chowdhury

is of the same opinion as far as translation of western literature

is concerned. The academy has translated works of Tolstoy

(Anna Kareninna), Dostoyevsky, Sartre, Rolla and many others,

but the quality remains suspect. One reason for that is, as

Chowdhury thinks, translation of non-English literary works

are not done directly from the original text, but often from

the English translation. So, it becomes a re-translation of

a translated work and most often much of the greatness of

the original work is lost in the process," he explains. Chowdhury

is of the same opinion as far as translation of western literature

is concerned. The academy has translated works of Tolstoy

(Anna Kareninna), Dostoyevsky, Sartre, Rolla and many others,

but the quality remains suspect. One reason for that is, as

Chowdhury thinks, translation of non-English literary works

are not done directly from the original text, but often from

the English translation. So, it becomes a re-translation of

a translated work and most often much of the greatness of

the original work is lost in the process," he explains.

Chowdhury

greatly appreciates the effort of Biswa Shahittya Kendra in

this regard, which he believes has got quite a good number

of translation works to its credit. He himself has translated

Greek playwright Aristophanes' "Bird" and "Frogs"

for the Kendra. He also talks of some publishing houses like

Oitijya and Samoy among others who have done some commendable

work.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|