|

||

Education in a competitive world -- Dr S.M.A. Faiz Higher education deficits in a drift -- Abdul Mannan Education for All-Beyond business as usual -- Rasheda K. Choudhury Islamic education heritage -- Dr A.M. Choudhury Economic diplomacy: Awaiting thrust -- Muhammad Zamir A wake-up call -- S. M. Rashed Ahmed Chowdhury New opportunities: New Challenges -- Syed Muazzem Ali Foreign relations: Taking a direction -- Ashfaqur Rahman Indo-Bangla ties: Old shadow, new vista -- C M Shafi Sami Towards a kinder, gentler peacekeeping -- Tazreena Sajjad Independence of the Higher Judiciary -- Asif Nazrul Problems of delay and backlog cases -- Dr. M. Shah Alam Juggling freedom and responsibility -- Shahid Alam Tourism in Bangladesh -- G. M. Quader MP The industrial policy dilemma -- Zahid Hussain 'Consumer redress' and 'empty pocket blues' -- Tureen Afroz How assertive has the Election Commission been? -- Manzoor Hasan Does the Election Commission exercise all its powers? --Mohammad Abu Hena Adivasi's tears and grief -- Sareeta Haider Architecture: How Green is Green? -- Ar. Zebun Nasreen Ahmed Chittagong Hill Tracts: Development without peace -- Naeem Mohaiemen Revisiting the BDR saga -- Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan ndc, psc, (Retd) Sexual harassment and our morals police -- Hana Shams Ahmed Garnering efforts is a sign of growing up -- Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed Rationalising the Intelligence services -- Muhammad Nurul Huda

|

||

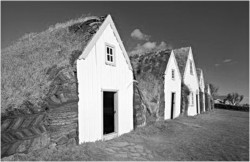

Architecture: How Green is Green? Ar. Zebun Nasreen Ahmed

ONE of the most pressing issues faced by architects today involves tackling the 'green' issue. What does 'green' mean to architecture and how do we approach it? How green is green architecture? This piece attempts to define green in terms of things Architects must achieve in order to create sustainability in the environment. With the immediate threat of climate change such a discussion is vital, as buildings through inefficient energy use can largely contribute to the change. Buildings, being very permanent features of the landscape, if not designed with energy efficiency in mind, will continue to deplete energy for a very long time and the responsibility of architects, planners and engineers in the matter is undeniable. Green architecture is not only about including vegetation or nature into architecture. On the other hand, in a completely different approach to design, it takes into account the interconnectedness of nature and creation. In this sense it is an approach that visualises design as a linked component in the universe, not as a stand-alone, one-off exercise. It recognises that in its creation, architecture forever alters the existing state of life. It is up to the architect/designer to see that the alteration is positive and that the building/architecture is a sustainable one one that will not strain resources and will not infringe on the rights of future generations to lead comfortable lives. Sustainability or 'greenness' concerns three separate issues often termed the triple bottom line the 3 Es of Ecology, Economy and Equity or the 3 Ps of Planet, Prosperity and People. It has been defined as development that does not compromise the ability of future generations to live and enjoy the planet. But buildings by their very presence modify peripheral conditions by changing the solar, temperature, wind and humidity regimes of the immediate site. Buildings also consume energy to create comfort for users. If designed sustainably, the extent of interaction and consumption can be controlled. This is the task of designers professionals responsible for the built environment architects, planners and engineers. The resultant building activity would then be termed 'green' and is more a process than a product thus requiring continuity during all stages of its life-cycle during design, construction, occupation and disposal. Only when such a holistic attitude is taken can the resulting architecture be termed 'green'. Architects are trained to design passively utilising forces of nature, to enhance the interior environment and minimise the use of active energy. Proper application of this knowledge would take care of the first of the Es, ecology, mentioned above. The second of the Es the economy is also considered by the architect, when clients are presented alternatives to chose from, according to their tastes and budgets. Conventionally however, short-term implementation costs far out-weigh life-time costing considerations. 'Green' considerations would take into account the manufacture, transportation, installation costs, as well as running costs and costs of dismantling and disposal monetary costs as well as the cost to the environment. The conventional architect/designer is ill-prepared in such wider considerations. Equity, the third E factor, is even more obscure for architects and other design professionals. Being conventionally dependent on a rich clientele for projects, this presents a number of difficulties to architects and the profession. The main problem is that the ones most affected by environmental degradation, the countless, nameless majority the people who cannot afford the services and prices of specialisation are the ones who suffer most when the built environment is not sustainable. They have neither the power nor the means, to control the environment. In this sense, architects catering to the rich, increase the disparity between those who can afford their services and those who cannot. It is beyond doubt that buildings are degrading the environment and causing climate change and environmental refugees are increasing. With it is the mounting demand for housing, healthcare facilities, educational institutions and other utilities. Architects rarely have the time, opportunity or will, to respond to such needs. Sadly, architectural training at the moment does not include any course on social responsibility. A change of attitude is now vital for the profession to combat the sustainability issue, and become green. And the awareness has to begin at the training/teaching level but carryover into the implementation level. In order to do that, Architects must include the local community in participatory decision-making at the inception of any project. The latter are the main Stakeholders being most affected by the consequences of design, which in the case of the built environment, are usually long-lasting. The participatory attitude will also ensure that the locals associate themselves with the success of a project, which improves its chances of maintenance and sustenance.

Architects of course, cannot be held solely responsible for issues of disparity between the different classes in any society, but it falls within their task to ensure that these differences are not more pronounced through the consequences of any design. No section of society should feel left out in the final output this sort of democratic attitude requires equal attention towards the needs of men and women, towards people of different faiths and economic backgrounds, as well as towards those with special physical needs an attitude of tolerance to all colours. And green cannot be defined by less. To sum up, green architecture deals with the design of buildings with minimum impact on the region, whether impacting on the environment, the economy or society at large. Furthermore, life-cycle analyses should be made, as buildings are notorious for long term effects. A brief list follows which mentions how this attitude is addressed at different stages of any design. 1. pre-design stage site analysis to find locations identifying advantageous use of natural forces (wind, sun, rainwater, daylight, topography, vegetation) community participation, to find needs of society 2. conceptual stage planning passive design features to ensure building layout, material selection, detailing for energy efficiency, minimising active energy use 3. design stage optimisation of active (operational) energy use with energy efficient appliances and, where possible, renewable energy material selection, preferably of low embedded (transportation and manufacturing) energy and high biodegradability quality control of indoor environment with natural ventilation and daylight, providing healthy and comfortable interiors for occupants, in accordance with functional needs and standards management of resources like rainwater which being abundant in Bangladesh should provide for much of the water needs of the building 4. building occupation recycling resources like water, eg. grey water can be used for flushing, washing, irrigation, etc. disposal of waste, where possible its reuse in different phases of the life of the function, and where needed, its safe disposal The main attitude shift in design for green architecture is to take a holistic attitude and to consider long term effects rather than short term goals and this should be reflected in any cost analysis predicting the benefits of the project. Bangladesh is already facing an environmental crisis. And the crisis is not restricted by national boundaries it is a global one. Time is running out. And in the meantime the planet will not wait for our answer. The consequences of our buildings are already undeniable Architects and building professionals have to take responsibility for what Dhaka has now become or any other city in Bangladesh, for that matter. Now is the time to act. And there is only one way to act green. |

||

© thedailystar.net, 2010. All Rights Reserved |