|

||||||||

Education in a competitive world -- Dr S.M.A. Faiz Higher education deficits in a drift -- Abdul Mannan Education for All-Beyond business as usual -- Rasheda K. Choudhury Islamic education heritage -- Dr A.M. Choudhury Economic diplomacy: Awaiting thrust -- Muhammad Zamir A wake-up call -- S. M. Rashed Ahmed Chowdhury New opportunities: New Challenges -- Syed Muazzem Ali Foreign relations: Taking a direction -- Ashfaqur Rahman Indo-Bangla ties: Old shadow, new vista -- C M Shafi Sami Towards a kinder, gentler peacekeeping -- Tazreena Sajjad Independence of the Higher Judiciary -- Asif Nazrul Problems of delay and backlog cases -- Dr. M. Shah Alam Juggling freedom and responsibility -- Shahid Alam Tourism in Bangladesh -- G. M. Quader MP The industrial policy dilemma -- Zahid Hussain 'Consumer redress' and 'empty pocket blues' -- Tureen Afroz How assertive has the Election Commission been? -- Manzoor Hasan Does the Election Commission exercise all its powers? --Mohammad Abu Hena Adivasi's tears and grief -- Sareeta Haider Architecture: How Green is Green? -- Ar. Zebun Nasreen Ahmed Chittagong Hill Tracts: Development without peace -- Naeem Mohaiemen Revisiting the BDR saga -- Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan ndc, psc, (Retd) Sexual harassment and our morals police -- Hana Shams Ahmed Garnering efforts is a sign of growing up -- Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed Rationalising the Intelligence services -- Muhammad Nurul Huda

|

||||||||

Indo-Bangla ties: Old shadow, new vista C M Shafi Sami

THE modern day Bangladesh, since before its birth, has been deeply related with India. Bangladesh- India relations were formally initiated on the 6th of December, 1971. Three days after the outbreak of the Indo-Pakistan war India accorded formal de jure recognition to the People's Republic of Bangladesh. During the preceding nine months of the glorious liberation struggle India extended moral and material support to the millions of refugees as well as to the valiant freedom fighters of Bangladesh. At the final phase of the war of liberation Indian soldiers along side Bangladesh freedom fighters shed their blood and laid down their lives to usher in a final victory. Indian diplomacy was marshaled in full strength and mobilized in top gear in mustering support for the cause of Bangladesh. The shared ideals and sacrifices forged a bilateral relationship that was based on the principles of mutual respect for each other's sovereignty and territorial integrity. The relations developed steadily after liberation into one of great amity and cordiality. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, released from incarceration in Pakistan, stopped over in New Delhi where he declared that “the peoples of India are the best friends of my people”. In February 1972 Bangabandhu sought the withdrawal of the Indian troops from Bangladesh and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ensured their withdrawal well ahead of the scheduled date of 25 March 1972. This introduced a new dimension of deference and esteem underscoring the concept of sovereign equality as well as a high degree of mutual trust and confidence in the bilateral relationship. The brutal and gruesome assassination of the founding father of the nation with all his family members- with the exception of his two daughters- suddenly and abruptly reversed the process of friendship. The wanton act of violence impacted violently on the steadily growing bilateral relations. India was appalled at the brutality committed on the family of Bangabandhu; it was equally distraught at the demolition of democracy in Bangladesh so soon after its restoration following a long and protracted struggle culminating in a war of liberation. Deeply troubled at having to deal with military regimes in Pakistan for long, India was flustered at the prospect of having to deal with a military dictatorship in its eastern flank also. In four short years Bangladesh India bilateral relations travelled from the zenith of euphoric amity and cordiality to the nadir of deep distrust and acrimony.

In the period that followed Bangladesh-India relations traversed a cyclical trajectory of bumpy stretches followed by smooth ones but always underlined by suspicion, mistrust and lack of confidence on each other's intentions. Unresolved issues lingered on and were allowed to assume a magnitude and dimension of outstanding disputes that seemed to defy any resolution as an environment of intractable attitudes prevailed. A happy and welcome break came in 1996 with the assumption of power in Bangladesh by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. A historic treaty on water sharing of the Ganges at Farakka was signed bringing an end to a dispute that bedeviled bilateral relations for more than two decades. This ensured for Bangladesh a fair and legitimate share of the Ganges water. Soon after this, another landmark agreement the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord was signed by the government of Bangladesh. The signing of this agreement was greatly facilitated by the abundant political good will that the government of India demonstrated. The Peace Accord brought peace and stability in a region of Bangladesh that had seen socio-political unrest and insurgency for decades as the Shanti Bahini insurgents formally laid down their arms and ended violence. These gains could not, however, be preserved and maintained for long. An unwelcome shadow was cast on the bilateral relations with the emergence of communal intolerance in Bangladesh following the elections of 2001 and coming into power of the successor government. Some irresponsible statements of the government leaders also somewhat vitiated the atmosphere. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina returned to power in Bangladesh in 2009 at a time when the Indian National Congress led by Sonia Gandhi, the daughter-in-law of Indira Gandhi was in power in India at the head of a coalition government. The welcome constellation in the bilateral firmament augured well for the friendly relations. Prime Minister Hasina seized the opportunity that was presented. At the Summit held recently in Delhi she and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh opened up a new vista of cooperation between the two countries. Rationale for cooperation This precept is of particular relevance in the case of Bangladesh India relations. Geographically Bangladesh is overarched by India which is a land mass of more than 3 million square kilometers, roughly 20 times the size of Bangladesh. The Bay of Bengal delineates Bangladesh in the south. On other three sides - west, north and east Bangladesh is surrounded by India; 95% of its more than 4000 kms land boundary is common with India, the remaining small stretch in the east is shared by Bangladesh with Myanmar. The land boundary with India is also highly porous. Bangladesh's principal rivers that serve as its life line run through the upper riparian India. Lower riparian Bangladesh is heavily dependent on the waters of these rivers for its agriculture, ecology and inland water transport. These factors coupled with the extensive cultural and ethnic bonds make the economic prosperity and well being of the two peoples inextricably interlinked. Strengthening of economic relations will promote the wellbeing of both the peoples of India and Bangladesh. Judged in the context of the comparative size of the two economies, it can safely be said that bilateral economic cooperation will bestow comparatively larger benefits to the people of Bangladesh. The globalised world has moved significantly away from the Chanakyan theory postulated in the 4th century BC that “Your neighbour is your natural enemy and the neighbour's neighbour is your friend.” The dynamics of inter state relations have also witnessed a retreat from the concept of realism propounded by the 5th century Greek historian Thucydides that interstate relations are based on might rather than right. His theory that stressed on the competitive and conflicting aspect of inter state relations is gradually but surely being replaced by the emerging new international norms of interdependence and cooperation between states. The modern world is one of common opportunities rooted in the realities of mutual dependence and growing interconnection. There is no reason for Bangladesh and India to view each other as adversarial or enemy state. On the contrary, the two countries face common enemies like underdevelopment, poverty, malnourishment and disease. On the contrary, the two countries face common enemies like underdevelopment, poverty, malnourishment and disease. The list of common enemies also include natural disasters like floods, cyclones and tsunamis as well as man made problems due to social, political and economic deprivations, ethnic strife, religious discord and the recently emerged militancy and terrorism. Bangladesh and India, irrespective of the asymmetry of the political power, economic strength and military might need each other to effectively combat these enemies. In an atmosphere of friendship and amity they can also maximize their political role and clout in world affairs. The evolving pattern of Indo-China relations offers a commendable example that is worthy of emulation by countries like Bangladesh. Despite a bitter history of mistrust and wars India and China are placing increasing emphasis on building economic relations. Trade between the two countries, which was less than $200 million at the beginning of the century, reached a new record at $ 18.71 billion in 2005. China has become India's second largest trading partner after the United States with India emerging as China's largest trading partner in South Asia. Indo-China trade is projected to grow to more than $30 billion in 2010, surpassing the current Indo-U.S. trade of $20 billion a year. India and China are also encouraging mutual investments in each other's territory.

Bangladesh also needs to be aware that a momentous phenomenon is taking place in the world. In one of the biggest revolutionary developments in recent history global economic power is shifting from the developed world to Asia; China and India. The two most populous countries in the world register an unprecedented economic growth. With this rapid growth coupled with expanding global trading relations and increasing diplomatic prestige these countries are emerging as global economic powers. Many international analysts believe that the 21st century will belong to China; many others hold that it might belong jointly to China and India. As they uplift millions of their citizens from poverty through rapid economic growth the Chinese dragon and the Indian elephant may jointly dominate the world economic arena for the foreseeable future. These countries are set to emerge as dynamos of economic development from which the neighbouring countries stand to derive immense advantage. Forging cooperative economic linkages with China and India will be of immense benefit to Bangladesh. As for India, it is the closest neighbour of Bangladesh. The two are bound by myriad linkages of history, culture, ethnicity, religion and geography. There is no reason for Bangladesh to see India's rise as a threat to its economic security. On the contrary India's rise offers Bangladesh an attractive window of opportunity. Bangladesh can derive enormous benefit through economic cooperation with its immediate neighbour. It will be prudent not to spurn that opportunity. Instead Bangladesh may remain ever ready to harness its rich potential to the fullest extent for the economic prosperity of its people. Issues and Challenges Strengthening cooperation The signing of agreements on security related issues including the one on combating terrorism is another commendable achievement. Bangladesh is committed to fight terrorism in all its manifestations. Successive governments in Bangladesh have repeatedly affirmed that it does not promote, nurture and encourage terrorism directed against any other country and that it does not allow its territory to be used by the terrorists. Undoubtedly, the rise of terrorism within the territory of Bangladesh is a grave threat that jeopardizes its socio-political life; it is a scourge that debilitates its economic fabric. Similarly, the rise and spread of terrorism in any neighbouring region with its spill over effects is an equally lethal threat. Terrorism is a common enemy of both the countries. The bold decision to sign an agreement to combat terrorism will help promote security and economic well being of the people of Bangladesh.

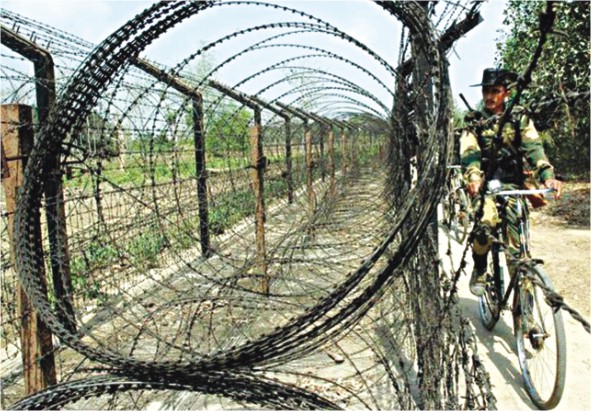

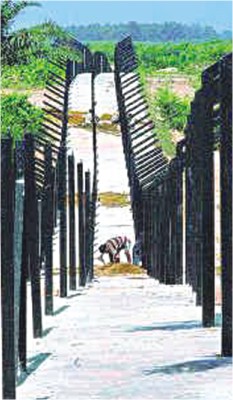

Solution to some of the pending issues is eminently achievable like the land boundary and related matters. Implementation of the Mujib-Indira Land Boundary Agreement signed in 1974 is on the top of outstanding issues. Bangladesh ratified the agreement forthwith. Bangladesh has also ceded southern half of South Berubari soon after the agreement was signed. Indian ratification of the Agreement is still awaited and it remains only partially implemented. The issue relating to the lease in perpetuity of Tin Bigha to Bangladesh is yet to be fully resolved and Bangladesh access to Angarpota and Dahagram remaining restricted and limited. The related issues of adverse possession of land and exchange of enclaves linger on. A stretch of 6.5 kms of land boundary is still not demarcated. Another prickly matter relates to the management of border between Bangladesh and India which has not been reflective of good neighbourly relations of the two countries. These visible management inadequacies that are manifested regularly rattle public mind and create a confidence deficit. These have also given a convenient tool in the hands of unfriendly elements in either country to trivialize Bangladesh-India friendship. Peaceful border management on the basis of respect for universal human rights is an easily doable matter but the political will was not forthcoming. The two Prime Ministers in their recent Summit have clearly marshalled that political will and have given firm directives to the bureaucratic and technical levels for resolution of these outstanding issues. Now it is necessary to take that process steadily forward and implement them. The issue of sharing of the waters of common rivers between India and Bangladesh is another long standing thorny problem. Negotiations on this vitally important matter have been very tardy and sluggish. Drastic fall in the water flow of this river during the lean season is a matter of great concern for irrigation and navigability in Bangladesh. The cumulative impact of upstream withdrawal of water from this river has caused adverse impact for the Teesta Barrage in Bangladesh. Teesta sharing, together with the sharing and other relevant issues pertaining to such important rivers as Feni, Monu, Muhuri, Khowai, Gumti, Dharla, Dudhkumar, Mohananda, Ichhamati, Korotoa et al. needed to be addressed with urgency. On this vexed issue of water sharing of common rivers also the Summit has given clear directives. For long the two countries have tended to view the matter only in the narrow context of zero-sum sharing. It is time the two countries look beyond the perceived short term concessions and take in to consideration the longer term benefits that could accrue to both the countries through imaginative harnessing of these abundant resources. The proposed Tipamukh project in North East India is another issue that has caused considerable anxiety and misgivings in Bangladesh as well as in the mind of the public in that region of India. The concerned state governments have also expressed their reservations. The worries arise from a lack of transparency of the project as also the adverse socio-economic and environmental impact on Bangladesh and that region of India. The assurance given by Indian Prime Minister that no harm will be done to Bangladesh is a welcome development. The Joint Rivers Commission will need to take appropriate follow up action to codify and translate this assurance in to reality. Maritime boundary is another critical matter that has far reaching consequences for Bangladesh. There are multiple and complex issues involved in this matter including the determination of the Hariabhanga border river boundary, the ownership of South Talpatty Island as well as the determination of boundaries of territorial waters, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf extending to up to 350 miles. It has very serious implications involving questions of its access to the high seas and its rights of exploitation of resources including oil, gas and other mineral resources in the Bay of Bengal. The consequences on its vital economic interests are enormous. It is a problematic and complex issue that has defied resolution through bilateral discussions. Broadly speaking the two countries do not agree on the basic principles of determining the maritime boundary -- Bangladesh preferring the principle of "equity" and India insisting on the principle of "equidistance". As a result the Bangladesh Government rightly decided to go for arbitration under the 1982 United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for a peaceful and equitable solution settlement. That approach notwithstanding there is an imperative need to continue to negotiate in parallel tracks with India at a political level. The issue has to be viewed in the greater perspective of friendly relations beyond the nitty-gritty of legal technicalities. For India the dispute involves no more than three per cent of its total economic zone and continental shelf in the Bay of Bengal while for Bangladesh their entirety is at stake. It is important to obtain Indian appreciation and understanding at high political level about the gravity of the comparatively enormous adverse economic consequences on Bangladesh in case of an unfavourable delimitation. The process initiated during the visit of the Prime Minister has to be taken forward with utmost sincerity and earnestness. Exploring new horizons Extensive negotiations have taken place for reducing this huge trade imbalance through preferential, duty free and easier access of Bangladeshi export to Indian market covering the whole range of tariff, para-tariff and non-tariff barriers. These negotiations have been remarkable for the presence of some conspicuous blind spots on either side of the negotiating table. For India, trade with Bangladesh is very small not exceeding 3% of its total global trade. India's import from Bangladesh is no more than a dismal 0.01% of its global import. Duty free access of Bangladeshi export in to Indian market and the dismantling of NTBs would not adversely impact on that country's economy or industry to any significant extent. Despite recognition of this reality at high political level the results of negotiations have been unassuming. There has also been lack of appreciation in India that increasing Bangladesh export to that country in the North East would contribute to the region's economic growth and in reducing its socio-political isolation to some extent. Decision making has been sluggish and implementation has been poor at best and incompatible with the spirit of the decisions at worst. Reduction of items in the negative list has been slow. Greater access granted by the union government of India has been negated in many cases by the imposition of barriers by the state governments. There has not been significant improvement in trade facilitation measures; harmonization and cooperation in banking and custom procedures; improvement and simplification of customs and administrative facilities in the two countries; and improvement of infrastructures in India to help land border trade. Over-land trade constitutes the major part of Bangladesh-India trade. For Bangladesh, trade with India is an important content of its total trade. India is the principal source of its import with 16% of its global import; India has emerged as Bangladesh's single largest source of import ahead of China and Singapore. Bangladesh export to India, however, remains an insignificant 1% of its total global export. Some political elements in Bangladesh exploit the trade imbalance with India to provoke an element of emotive controversy. Interestingly similar trade deficit with another friendly country China does not evoke much concern - and rightly so. However, about India's export to Bangladesh it is not recognized that the same is growing not because of any preferential treatment accorded to India but because geographical proximity and cultural identity lend their exports a competitive advantage. It is also not appreciated that it is the global trade deficit that is of vital concern for a country and the bilateral trade deficit with a given country is of little economic concern. Bangladesh imports from India comprise essential consumer goods, vitally necessary food grains and basic raw materials that help promote our export; and if Bangladesh were to import these items from geographically distant sources Bangladesh's global deficit would be further aggravated. Negotiations on this also seem to skirt a pertinent issue that regardless of the extent of duty free access of its export to India, export potential of Bangladesh to that country would continue to remain limited unless its production capacity and competitiveness improved significantly and unless the export basket of Bangladesh was significantly enlarged. An appropriate response to this problem would include attracting investment from India to set up joint ventures with buy-back arrangement for North East India. This will expand Bangladesh export basket and its enlarged export surplus can reap the advantage of proximity with North East India. This together with duty free access of Bangladeshi exports in to the Indian market, dismantling of NTBs, various trade facilitation measures and improved infrastructural facilities can make considerable contribution to the growth of Bangladeshi export to India. Another response would be to forge greater and expanded connectivity. This along with improved infrastructure can provide significant impetus to trade. In addition to reducing the cost of import, for Bangladesh connectivity offers a whole new array of services for export. Greater connectivity will also significantly stimulate Foreign Direct Investment from all over the globe both in the ports of Chittagong and Mongla as also in road, rail and other infrastructure development. Bangladesh can also derive a great deal of economic benefit through connectivity for Nepal and Bhutan utilising Mongla Port for their third country trade. Similar benefit can accrue from connectivity for North Eastern India utilising Chittagong Port. Enhanced trade, investment and connectivity have played a critical role in accelerating economic growth in various regions of the world including West Europe and China. Bangladesh can harvest similar gains. A new horizon of economic cooperation between Bangladesh and India has been opened. A new window of opportunity has been unlocked with rich potentials of economic benefits that could significantly contribute to the welfare and economic prosperity of the peoples for both the countries. The new vista also creates a win-win situation for both countries which is an indispensable ingredient for a fruitful and sustainable bilateral economic cooperation. Shaping the path ahead The author, a former adviser, caretaker government, secretary and an abmbassador. |

||||||||

© thedailystar.net, 2010. All Rights Reserved |