|

|

Education in a competitive world -- Dr S.M.A. Faiz Higher education deficits in a drift -- Abdul Mannan Education for All-Beyond business as usual -- Rasheda K. Choudhury Islamic education heritage -- Dr A.M. Choudhury Economic diplomacy: Awaiting thrust -- Muhammad Zamir A wake-up call -- S. M. Rashed Ahmed Chowdhury New opportunities: New Challenges -- Syed Muazzem Ali Foreign relations: Taking a direction -- Ashfaqur Rahman Indo-Bangla ties: Old shadow, new vista -- C M Shafi Sami Towards a kinder, gentler peacekeeping -- Tazreena Sajjad Independence of the Higher Judiciary -- Asif Nazrul Problems of delay and backlog cases -- Dr. M. Shah Alam Juggling freedom and responsibility -- Shahid Alam Tourism in Bangladesh -- G. M. Quader MP The industrial policy dilemma -- Zahid Hussain 'Consumer redress' and 'empty pocket blues' -- Tureen Afroz How assertive has the Election Commission been? -- Manzoor Hasan Does the Election Commission exercise all its powers? --Mohammad Abu Hena Adivasi's tears and grief -- Sareeta Haider Architecture: How Green is Green? -- Ar. Zebun Nasreen Ahmed Chittagong Hill Tracts: Development without peace -- Naeem Mohaiemen Revisiting the BDR saga -- Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan ndc, psc, (Retd) Sexual harassment and our morals police -- Hana Shams Ahmed Garnering efforts is a sign of growing up -- Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed Rationalising the Intelligence services -- Muhammad Nurul Huda

|

|

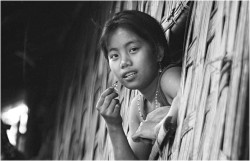

Chittagong Hill Tracts: Development without peace Naeem Mohaiemen

I once made a sardonic comment about the adibashi conundrum: "Don't think you're an agacha on our national boto brikkho. When there are visiting dignitaries or sports events, your people are very useful. You sing, you dance, you wear exotic, colorful clothes. A readymade National Geographic tableau." (Daily Star, April 6, 2007) With a sarcasm barb, there are elements of exaggeration mixed in with the facts. Two years after that essay was written, I joined friends at China-Bangladesh Moitree. In that moment, I felt uneasily that my sarcastic jibe was becoming reality: the tableau was the centerpiece. December was the twelfth anniversary of the signing of the CHT Accord that ended the guerilla war of the Shanti Bahini. A series of tie-in events: newspaper articles, seminars, talk shows, and then this: "Diversity Fair" organised by donor agencies. On stage, one after another adibashi dance form was being introduced in Bangla and English (but not, I noted, in Pahari languages). Outside, row after row of stalls selling adibashi clothes, products, food. As we walked out, we each received a nice pen with a EU logo and English text. There were Benetton-esque posters proclaiming unity through cultural diversity. I found the event politically blunt. But still, I reminded myself, a massive fair at the hall of China amity is a good sign. All this soft visibility, economic activity-- something good will come of it, trickle down or up. But meanwhile, what about the Accord? Post-1997 was a lost decade, when the CHT Accord stayed in limbo. Even worse than non-implementation, the region faced a hostile government from 2001-2006-- one that, let us not forget, ferociously opposed the Accord in 1997, and whose leader threatened to do "long march" against its' signing. The twelfth anniversary was a reminder that the Accord remained totally unimplemented, although there are some hopeful steps from the new government (propelled by a sense of opportunity). When we discuss the Accord, the primary issues we focus on are the resolution of land ownership (of Pahari land grabbed by settlers), return and rehabilitation of refugees (internally displaced and exiled to India), and demilitarisation (withdrawal of army camps). What also needs to be looked at is how the frozen status of the CHT Accord is deeply skewing the ongoing development work in the area. According to the 1997 Accord, all development work in the region is to be supervised by the Hill District Councils (HDC) of the three districts, which are to have 25 elected representatives (a total of 75 HDC representatives). The Regional Council is a supra-body that oversees all three districts, and all of this folds under the CHT Affairs Ministry. But since the Accord was not implemented, the HDCs are functioning with only 5 members, and they are all by nomination, not common vote. Thus the HDC is politically unaccountable, and ineffective due to missing members. The Accord also required that indigenous peoples' knowledge base and modes of development get priority. But actually there has only been a replication of development policy of the flatlands. Instead of pro-indigenous modes of development, the region has seen the implementation of "Modernisation": Tourism (garish and unsustainable results, coupled with land-grabbing by tourism industry aligned forces), Afforestation (critiqued by NGOs as unsustainable seeding of non-native varieties, and aggression on common land), Natural Resource Extraction (Phulbari is one example of resource extraction that harms indigenous populations), and finally Small & Medium Industry Development (theoretically excellent, but in practice Jumma capital cannot compete with Bengali capital, in absence of an indigenous-friendly policy). Another key issue is that many of the donor and multilateral agencies have come into the region with a program that is intended to be similar to post-conflict UN rebuilding operations, for example in East Timor. But past governments never allowed these agencies to implement the "sensitive" peace-building part of their mandate (e.g., establishing indigenous electronic media, indigenous police force, building up political capabilities). Instead the agencies were limited by the government to the more "innocuous" parts of the programs: usually health, horticulture and education. This half approach led to incomplete results. This winter, I went up to Rangamati for Raja Devasish Roy's royal Punya Darbar. The ceremonial pledging of allegiance by all the headmen of three districts is supposed to happen every year. Due to regional instability, it had been postponed for the last seven years. We were determined not to miss this one, and made it up there along with many other visitors. There was a tremendous crush of people at every event-- along with the regalia, were mela stalls. One evening at dinner, I thought it the right time to bring up the critiques of development work-- that it could not happen properly until the Accord was implemented. The table listened, and then one elder spoke. Listen, he explained, we all know why the Shanti Bahini fought the war. It was for our constitutional rights, for our self-representation, for the preservation of our way of life in the face of settler encroachment. But both sides conceded and made compromises in 1997. Yes, I replied, but since the Accord has not been implemented, it seems that in the end only Paharis fulfilled concessions (e.g., demobilization of the guerilla army). He nodded in agreement, and then gently nudged it back to the realpolitik part of the conversation. The biggest achievement of the Accord, he argued, even in it's non-implementation, is that the region is more stable. The NGOs and Donors working here are creating an education and development infrastructure, so that where Paharis had nothing, they are finally seeing small progress steps. Even the simple fact of greater visibility of Paharis in public and civil society spaces is a huge gain. Not enough, but something. And eventually, a more empowered Pahari population can start demanding their rights, which includes full implementation of the Accord. I understood his sentiment to be a variation of WEB Dubois' "Talented Tenth" theory of Black Empowerment. When the Shanti Bahini demobolized, the hills became open to NGOs and donor agencies to begin development work. But besides the NGO sector, the hills also saw the arrival of business and political forces hostile to the Paharis. The presence of Bengali settlers, financially incentive by multiple governments to settle in the CHT is the continuous and growing force of destabilisation in the region. Over the last few decades, a steady inflow of settlers reduced the Pahari population from a onetime majority of their land, to now almost parity at 55%. At current rates of internal migration, the Paharis will become numeric minorities in their own districts. This ethnic displacement has been matched by electoral politics. In the 2008 national elections, the two main political parties representing the Paharis (JSS and UPDF) were barred by the Election Commission from contesting, on a technicality. Bengali settlers were also included in the Pahari voter list for the December 2008 national elections. In this manner the flow of numeric ethnic displacement is becoming permanent position through electoral muscle flexing and related marginalisation. ("The Missing Pahari Vote", Daily Star, 1/12/08) An anthropologist friend argues that the feminist organizers moved away from movement based politics in the 1980s, after it became part of the NGO sector. Donor criteria meant confrontational modes were replaced by more legalistic, reformist, and programme-oriented modes. Something similar may be happening in the Pahari movement as well. The creation of a white-collar service sector within the Pahari community, employed by NGOs, is a positive step towards creating a population that can press for their own rights through new platforms. But the polite, go-slow modes of seminars, essays, research papers, while productive, should not blind us to the the political fact of non-implementation of CHT Accord. The Paharis kept their side of the 1997 negotiations, disbanding the guerilla army, and dropping key parts of their long-standing demands. Time for the government to fulfill its promise, through a full, unconditional implementation of the Accord. Naeem Mohaiemen is a member of Drishtipat, and wrote about ethnic and religious minorities for several Ain o Salish Kendra annual reports. |

|

© thedailystar.net, 2010. All Rights Reserved |